| Other than the traditionally recognized bandage soft lenses, there are

other therapeutic uses for contact lenses. Some are soft lenses; many

are rigid lenses, typically rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses. Specialty

lenses are mostly used in situations in which neither spectacles nor

a conventional lens would improve visual acuity or relieve patients from

debilitating symptoms. Some examples are keratoconus, after corneal

transplantation, irregular astigmatism of various etiologies, color

deficiency (particularly red-green), diplopia, anisometropia, cosmetically

unsightly eyes, iris abnormalities with resultant monocular diplopia, photophobia, glare, halos, or decreased vision. KERATOCONUS DESIGN LENSES Patients with keratoconus disease comprise a significant portion of the

population of therapeutic contact lens wearers (Figs. 3 and 4). Although patients with early forms of the disease may obtain reasonably

good visual acuity with either spectacles or conventional soft lenses, most

patients require special design, rigid lenses to obtain functional

vision. Eliminating the need for corneal transplantation would

be ideal. Because of the high degree of irregular astigmatism and the

nature and location of the ectasia that patients with keratoconus have, conventional

lens fitting does not provide these patients with either

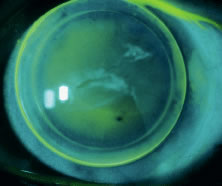

an adequate fit or reasonable comfort or visual acuity.  Fig. 3. Keratoconus. Corneal ectasia outline using retro illumination. Fig. 3. Keratoconus. Corneal ectasia outline using retro illumination.

|

Fig. 4. Keratoconus—Munson's sign. Fig. 4. Keratoconus—Munson's sign.

|

The purpose of a contact lens in patients with keratoconus is to cover

the irregular astigmatism and the distorted anterior surface of the ectatic

cornea, thus providing a regular, spherical optical surface in front

of the eye. The lens would effectively restore the smooth optical

properties of the cornea (Figs. 5 and 6).  Fig. 5. Advanced keratoconus fit with Nicone RGP lens with resultant 20/25 vision. Fig. 5. Advanced keratoconus fit with Nicone RGP lens with resultant 20/25 vision.

|

Fig. 6. Fellow eye of patient in Figure 5—after penetrating keratoplasty. Acuity without correction: 20/200 Fit

with keratoconus lens design improving visual acuity to 20/30. Fig. 6. Fellow eye of patient in Figure 5—after penetrating keratoplasty. Acuity without correction: 20/200 Fit

with keratoconus lens design improving visual acuity to 20/30.

|

There are numerous keratoconus lens designs available in the market. The

primary goal of each design is to allow adequate fitting over the diseased

cornea with minimal or no direct mechanical trauma to the normal

tissue. This is typically accomplished with designs that incorporate

several different posterior curvatures in which the central curvature

is steeper and the peripheral curves are flatter. Some lenses are bicurved, tricurved, or

even multicurved. Aspheric lenses are often used. Some of the lens designs available today for patients with keratoconus

include: - Soper Cone—bicurved

- Nicone—tricurved (Fig. 7)

- Aspheric lenses (complex)

- Mc Guire

- Rose K

- Comfort Kone

- KAS Lens

- Valley K

- Porus K

- Formacon

- Piggy-back lenses

- Softperm (hybrid)

- Scleral (haptic) lenses

- Flexlens Tricurve keratoconus lens (soft)

- Flexlens Harrison keratoconus lens (soft)

- Dura-T

Fig. 7. Nicone lens design—for keratoconus patients. Fig. 7. Nicone lens design—for keratoconus patients.

|

Although some of these lenses may be available in PMMA hard lens material, it

is highly recommended that gas permeable materials be used to avoid

further compromise on an already diseased cornea. In the hands of an experienced contact lens fitter, most moderate and many

advanced cases of keratoconus can be successfully fitted with contact

lenses (Fig. 8). Today, a much lower percentage of keratoconus patients require corneal

transplantation, because of the technologic advances and the many contact

lens options available.  Fig. 8. Keratoconus patient successfully fit with Nicone lens. Fig. 8. Keratoconus patient successfully fit with Nicone lens.

|

IRREGULAR ASTIGMATISM Significant irregular astigmatism can result from ocular surgery, although

it is most commonly seen in patients with penetrating injuries or

in patients with significant corneal surface pathology. When the amount

and extent of the irregular astigmatism is mild, soft contact lenses

can be used successfully. When soft lenses are used, it is recommended

that a thick lens be used. The thicker lenses will allow less flexure, thus

creating an effective tear-lens layer. In most cases, a rigid lens is needed due to the large amount of irregular

astigmatism. Rigid lenses will usually provide patients with a better

visual acuity. Whenever possible, a thin, spherical gas permeable

lens is preferred. The fitting technique may vary, although care should

be given to protecting the cornea from lens trauma to the areas of protrusion (Fig. 9). Although a relatively thin lens is recommended, flexure will be a problem

if the lens selected is too thin. In patients who cannot tolerate

rigid lenses, either piggy-back lenses or a hybrid lens may be used

successfully.  Fig. 9. Advanced keratoconus fit with special design (Nicone) RGP lens. Fig. 9. Advanced keratoconus fit with special design (Nicone) RGP lens.

|

The initial lens selection may be difficult because of the inability to

obtain accurate keratometric readings. If keratometry is not possible, it

may be helpful to use keratometric readings from the fellow eye. Whenever

possible, corneal topography is recommended because it is usually

helpful in visualizing the cornea of patients with irregular astigmatism. With

the use of corneal topography combined with a computerized

lens design program, highly specialized lenses may be generated to

fit the difficult patient. PIGGY-BACK LENSES The piggy-back lens concept is basically the wearing of both a soft and

a rigid contact lens to provide the patient with the good visual acuity

of a rigid lens and the comfort of a soft lens. In the piggy-back lens

system, the patient wears a soft lens against the cornea, which provides

comfort, and a rigid lens over the soft lens to obtain good, useful

vision. Piggy-back lenses are typically used in cases of keratoconus or in patients

with irregular astigmatism after a penetrating keratoplasty or as

a result of a penetrating injury (traumatic). Standard soft lenses are applied to create a new anterior surface of the

lens/cornea combination. On the surface of the soft lens, the appropriate

RGP lens is placed. The rigid lens typically has a steep central

posterior curve surrounded by a flatter peripheral zone. The steep central

zone stabilizes on the corneal cap while the flatter zone rests

on the periphery of the soft lens. Some laboratories will create a custom

lens with an anterior depression in the soft lens in order for the

rigid lens to fit properly. This feature provides better centration because

the rigid lens fit into the shallow depression of the soft lens. The primary advantage of the piggy-back lens system is comfort. Disadvantages

include: cost, extensive patient education, and laborious care

and handling of the lenses. A possible complication is decreased oxygen

permeability, because there are two superimposed lenses over the corneal

surface. This is of particular concern in these patients because

the corneas are already diseased and/or compromised. CONTACT LENSES FOR SPORTS Generally, soft contact lenses are preferred for any contact sports or

athletics because of the danger of the rigid lens being displaced off

the cornea or even out of the eye. This has happened so frequently that

the National Basketball Association has passed a rule that games cannot

be stopped to look for a lens that accidentally pops out of a team

member's eye. Athletes often need rigid lenses to obtain the desired or needed visual

results. In these cases, a large-diameter lens must be fitted. These

large-diameter lenses can often be tolerated for only 4 to 5 hours at

a time. To provide the best possible fit with increased wearing time, lenses with

additional peripheral curves are often used. The larger diameter will

provide increased apical vaulting that requires peripheral modifications. Aspherical

lenses are best for these circumstances. These may be

available in diameters as large as 10.0 mm. Aspherical lenses offer

the following advantages: not easily dislodged; better comfort; improved

visual acuity; and less photophobia because of the better fit and larger

optical zone, therefore, they are better tolerated. Soft lenses are typically preferred for contact sports because they move

the least and are almost impossible to dislodge. Soft lenses will also

follow sudden eye movements well, thus improving performance. They

also cause less photophobia and are extremely comfortable. Wearing time

is flexible with soft lenses. Dust and foreign bodies do not usually

affect wear as is the case with rigid lenses, because dust and foreign

bodies do not become trapped underneath the lens. Whenever possible, soft

lenses are best for soccer, basketball, softball, football, tennis, rugby, cricket, lacrosse, polo, squash, racquetball, skiing, hockey, and

other contact sports. The major disadvantage of soft lenses is

that the contrast sensitivity is not quite as good as that of RGP lenses. NYSTAGMUS Patients with congenital nystagmus see poorly with glasses. The oscillations

of the eyes with spectacles produce constant parallax. With contact

lenses, the visual disturbance that is created by the constant eye

movements against a fixed spectacle is greatly reduced, thus improving

the functional vision. The visual gains for nystagmus patients can be

remarkable and can be improved from 20/200 to 20/50 or even better with

the use of contact lenses. As fixation is improved by the corrective lenses, the actual amplitude

of the oscillations may decrease. This is particularly noticeable under

dim illumination. Most patients with nystagmus seem to have a large amount of astigmatism. Properly

correcting the astigmatism is of utmost importance, particularly

when the goal is to improve the patient's overall visual acuity. Some

prefer fitting these patients with large-diameter RGP lenses, although

some of us prefer to use soft toric lenses, often custom made, with

good axis stability. The advantage of the soft lens, which is

used whenever possible, is greater axis stability with the nystagmus. Patients with albinism almost invariably have a significant nystagmus and

large amounts of astigmatism. These patients not only benefit from

contact lenses for the reasons discussed previously but also benefit from

a tinted lens to decrease the photophobia that they have as a result

of the translucent iris. Decreasing the photophobia will also enhance

their vision, as well as their comfort and functionality. ORTHOKERATOLOGY Orthokeratology is a method of correction of refractive errors using a

series of rigid contact lenses to change the shape of the cornea, thus

altering the refractive error. It is said to be a system for “sight

without glasses.” Orthokeratology has been available for many

years although its popularity has varied through the years. With the

increasing popularity of refractive surgery, orthokeratology has become

somewhat more popular. Its reversibility has made it an attractive

alternative to refractive surgery. The premise behind the system is that progressive flattening of the cornea

through the use of a series of flatter fitting lenses will eliminate

myopia. The assumption is made that the degree of flattening will be

uniform in all meridians. Certainly this is not always the case. Flat

fitting lenses worn over a long period may result in a toric cornea. The advocates of orthokeratology point to its usefulness in treating certain

groups of patients who require good vision and cannot wear contact

lenses. With orthokeratology, lenses can be applied as night lenses and removed

during the day. The night wearing maintains the flatness of the cornea (retainer

effect). Lenses must be reassessed at least every 6 weeks

with repeated attention to the refraction. New corneal readings and slit

lamp evaluation of the cornea is required. When changes in the corneal

curvature occur, new flatter lenses are provided. Often a retainer plano lens is worn, sometimes for a minimum wearing schedule, to

keep the cornea flat. Most ophthalmologists have very limited

experience with orthokeratology. Complications such as over-wear reactions, corneal abrasions, induced corneal

astigmatism, corneal warpage, and ocular discomfort from the wearing

of such a large, flat lens can occur. The main objections of orthokeratology

are (1) corneal complications from the use of overnight contact

lens wear (e.g., hypoxia, corneal edema), (2) cost and time expenditure, (3) unpredictable effectiveness and inability to screen patients

for accurate patient selection, (4) necessity of a retainer contact

lens, and (5) usefulness only in myopic patients. AFTER REFRACTIVE SURGERY As refractive surgery has become increasingly popular, the need for specialized

contact lens fitting after refractive surgery has increased significantly. There

are several uses or needs for contact lenses after

refractive surgery: (1) “molding lens” to reshape the cornea

and promote healing under the laser-assisted in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK) flap, (2) bandage—to minimize pain in cases of photoreactive

keratectomy (PRK) or in cases in which there is any abrasion occurring

with LASIK or any other refractive procedure, (3) correction of

irregular astigmatism resulting from the surgery, (4) correction of

any residual refractive error not corrected by the surgery, (5) treatment

of anisometropia in patients that have only undergone surgery in one

eye, and (6) others. Following refractive surgery, patients usually have a very different and

distinct corneal anatomy that often makes lens fitting difficult. This

is especially the case with patients who have undergone RK and similar

procedures. Their corneal anatomy is quite different than that of

nonsurgical patients. New lens designs, particularly rigid lenses, have been developed to fit

these patients. Similar to postkeratoplasty patients, the corneas of

these patients have a flat central area surrounded by a steeper periphery. Conventional

lenses cannot be successfully fit in most of these patients. POSTTRAUMATIC Patients who suffer penetrating injuries to the eye often need or benefit

from contact lenses. As mentioned earlier, the correction of irregular

astigmatism is best accomplished with the use of a rigid lens. Irregular

astigmatism cannot usually be corrected with either spectacles

or soft lenses. Most patients with penetrating injuries have resultant

irregular astigmatism. Large ametropias often require contact lenses to avoid anisoconia and diplopia

and to achieve functional visual acuity. Monocular aphakia is

a common complication of trauma. Restoration of vision is accomplished

with the use of a contact lens whenever intraocular lens implantation

is not feasible or contraindicated. Posttraumatic iris abnormalities are another common complication after

penetrating trauma: traumatic mydriasis and traumatic partial or total

aniridia. These abnormalities are often best corrected with the use of

an iris-painted soft contact lens. Lens use in these cases can be beneficial

both cosmetically and functionally. Cosmetically, covering an

unsightly eye can help the patient recover emotionally and can improve

the self-esteem. Functionally, correcting the iris anomalies can eliminate glare, flare, halos, and

monocular diplopia. Strabismic abnormalities often develop

after trauma that will often cause diplopia. A black pupil lens can offer

occlusion that will eliminate the diplopia. Thorough evaluation of a posttraumatic patient can identify problems and

deficiencies that are often treatable with the use of a contact lens. Combinations

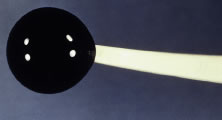

can be custom made to treat these patients. OCCLUSION THERAPY Amblyopia and diplopia are the two primary indications for occlusion therapy. Occlusion

therapy has been most commonly done with patches, but

contact lenses are a more palatable, cosmetically acceptable option for

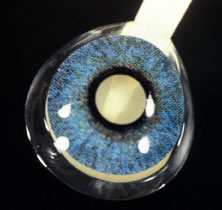

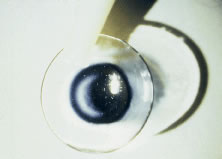

many patients (Figs. 10 and 11).  Fig. 10. Occluder (soft) contact lens. Fig. 10. Occluder (soft) contact lens.

|

Fig. 11. Soft occluder lens—clear periphery with black pupil only. Fig. 11. Soft occluder lens—clear periphery with black pupil only.

|

The use of occluder lenses in children for the treatment of amblyopia has

been somewhat controversial. Conservatives believe that the risks of

a contact lens outweigh their benefits. Concerns about infections are

the main focus of this controversy. Another concern is hypoxia and the

complications associated with extended wear because these very young

patients do spend a significant percentage of their days sleeping. They

are not often used but, whenever used, they are usually quite successful. Contact lenses are a very successful tool in the treatment of diplopia, both

monocular and binocular. Strabismus, neurologic disorders, and trauma

are the most common causes of diplopia. In most cases the diplopia

is binocular, although, in trauma cases monocular diplopia associated

with iris anomalies is not uncommon. Patients with diplopia are often

quite debilitated with the symptoms, and the relief offered by the

lenses is usually quite welcome. Depending on the anatomy of the eye, these lenses can be either an occluder (black-out) lens

or a simple black pupil lens. The traditional black-out

lens is a soft lens that is painted black and totally opaque on

its entire surface. Although successful in providing coverage of the

visual axis, thus relieving the symptoms, it is not cosmetically appealing, especially

in patients with light colored eyes. The most commonly

used type of lens is a clear soft contact lens with a black pupil in

the center. The pupillary diameter will vary depending on the patient's

pupil diameter and positioning of the eye. Careful attention

must be paid to the position of the eye to avoid allowing light and vision

through the periphery of the painted pupil. In many cases it is necessary

to enhance the occluder effect of the lens, because patients

can still see through the lens, and thus symptoms are not eliminated. A

technique that can be used with great success is the use of a contact

lens with a power that is completely different than the patient's

refractive error. This lens (power) will provide some significant blurring

of the vision that, together with the blocking effect of the black

pupil, will in fact obstruct the vision. Although some patients report

some vision out of the eye with the lens, most are able to learn

to suppress the image in the covered eye enough to obtain symptom relief. In patients with monocular diplopia, the symptoms are caused by iris abnormalities

that in effect create two different visual axis. In most cases

the iris abnormalities are traumatic, although they can be iatrogenic (as

in patients with peripheral iridectomies that are not covered

by the eyelids). Although rare, monocular “multiplopia” can

occur. This is usually seen in trauma patients or in patients that

have undergone multiple intraocular surgeries and have several iridectomies

that are not covered by the eyelids. In patients with monocular diplopia, the type of occluder lens needed is

usually different, because the goal of therapy in these patients is

to create a single pupil. These patients typically require an opaque iris-painted

lens that will cover the entire iris and creates a single, central, clear

pupil. These types of lenses are usually more complex

to fit but are usually quite successful. COLOR DEFICIENCIES Approximately 8% to 10% of males and 0.5% of females have some impairment

in color vision ranging from a mild deficiency to an almost complete

impairment. The defect is most commonly in the red-green range. Although

yellow-blue deficiencies are seen, they are much less common. The X-Chrom lens can be used successfully to treat these patients (Fig. 12). The X-Chrom lens transmits light in the red zone from 590 to 700 nm (spectrum

of white light is 380 to 760 nm), thus improving color discrimination

in patients with partial impairment in the red-green range. The

lens is bright red, usually rigid, and fitted to the nondominant eye. The

other eye either remains uncovered or is fitted with a conventional

lens for the correction of any ametropias that the patient might

have (the X-Chrom lens can be obtained in any power, so that it can also

correct any refractive error). The uncovered eye will perceive a red-green

object as usual, but the eye with the red lens will perceive

the red wavelengths of light and will absorb the green wavelengths. The

brain now receives two different intensities. By a rapid self-learning

process, the patient can identify both colors properly.  Fig. 12. X-Chrom lens (bright red rigid lens) for red-green color deficiency. Fig. 12. X-Chrom lens (bright red rigid lens) for red-green color deficiency.

|

We have significant experience with this lens with reasonably good results. Although

the lens does not correct the color defect, it does permit

patients to make a discriminatory judgment of color. During the initial

patient evaluation, it is very helpful to use a trial lens to evaluate

effectiveness. Patients can often improve their results in the Ishihara

plates from properly identifying 1/15 plates to identifying 10/15 to 13/15 correct

plates. Proper color discrimination is very important

in numerous professions such as: electrical engineers, uniformed

forces, artists, painters, printers, decorators, and all those professions

in which color discrimination is important. A word of caution to patients wearing the X-Chrom lens: This lens has detrimental

effects on space localization of moving objects and other aspects

of binocular vision. Persons operating moving vehicles wearing

a tinted lens over one eye may experience hazardous distortions of the

positions of perceived objects and may, therefore, be dangerous drivers

in certain circumstances. Conservative judgments are justified until

the extent of the hazards is better understood. Ideal lens fitting involves special attention to avoiding excessive lens

movement and decreasing lens thickness to improve visual results. Otherwise, techniques

used for fitting any other conventional rigid lens

should be applied. Motivation is quite important because the lens may

be cosmetically undesirable (bright red lens in only one eye) and there

is an adaptation period that the patients must undergo. The use of

bright ambient light is highly recommended to maximize results. THERAPEUTIC USES OF PAINTED LENSES Painted contact lenses have a variety of uses: cosmetic, therapeutic, handling, and

informational. Although a valuable tool in total patient

care, the therapeutic use of tinted lenses is, unfortunately, not often

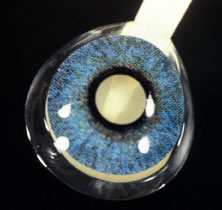

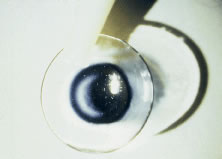

considered. There are several basic categories or types of painted lenses that can

be obtained, considering that multiple variables can be incorporated into

any of these lenses. As a general rule, soft (hydrophilic) lenses

are used for painting in therapeutic lenses (although rigid lenses may

be used rarely). The broad categories of tints include: translucent (Fig. 13); opaque (iris) (Fig. 14), with or without pupillary opening; clear or black pupil; clear lens

with black pupil only (Fig. 15), totally black (occluder) (Fig. 16) lens, and others. Although some lenses are commercially available (with

predetermined colors and options), others are custom made for each

patient. The type of lens chosen for each patient will be dictated by

the patient's needs and desires. As a general rule, custom made lenses

will be more costly and take longer to obtain but usually accomplish

a better cosmetic result and, therefore, greater success. Painted

lenses can be obtained with or without refractive power, depending on

the patient's needs.  Fig. 13. Translucent iris-painted lens with black pupil. Fig. 13. Translucent iris-painted lens with black pupil.

|

Fig. 14. Opaque iris-painted lens with clear pupil. Fig. 14. Opaque iris-painted lens with clear pupil.

|

Fig. 15. Clear lens with black pupil. Fig. 15. Clear lens with black pupil.

|

Fig. 16. Opaque black lens (occluder). Fig. 16. Opaque black lens (occluder).

|

Indications for the use of therapeutic painted lenses include: covering

corneal scars, creation of a pupil, pupillary occlusion, diplopia, heterochromia, phthisis, amblyopia, aniridia, and photophobia. While evaluating a patient for a painted lens, we must take into consideration

not only the obvious cosmetic or clinical deformities but also

the patient's realistic needs, desires, and expectations. It could

be quite frustrating if unrealistic expectations are set or the patient's

needs are not met. - Covering corneal scars—pathologic or traumatic, (Figs. 17 and 18) severe corneal neovascularization, aphakic bullous keratopathy, infections, penetrating

injuries, and phthisis. In these cases, an iris-painted

lens with a black pupil is needed. Occasionally a clear pupil may

be necessary if the eye has functional vision. The iris may be covered

with a dark brown translucent lens if the iris in the counter eye is

very dark brown as well. Otherwise, an opaque iris lens may be necessary.

- Creation of a pupil—traumatic or surgical. Pupillary defects are

most commonly seen as a result of trauma (blunt or penetrating), although

surgically induced defects can often be seen as well, for example: removal

of iris tumors (Fig. 19), intra-operative difficulties, anisocoria, and others. For these cases, opaque

iris-painted lenses with a clear pupillary opening are usually

necessary.

- Occlusion of pupil—amblyopia, leukocoria (Figs. 20 and 21). The condition may be cosmetic or therapeutic. For the treatment of amblyopia

in a child, an opaque black lens may be used. Cosmetically, patients

with leukocoria may also benefit from a similar lens.

- Diplopia—monocular or binocular. Diplopia may occur in patients with

neurologic disorders, acquired strabismus, and others. Monocular diplopia

may be seen in patients with traumatic or surgically induced peripheral

iridectomies that are within the interpalpebral fissure. There

may be other causes. A lens with a painted black pupil, with or without

a painted iris, may be quite successful.

- Heterochromia—congenital or acquired. Patients who have heterochromia

are often very self-conscious of their cosmetic appearance. This

may be corrected with the use of an opaque iris-painted lens colored to

match the opposite eye. This is usually done to match the darker eye. Occasionally, lenses

may need to be used in both eyes to obtain a good

cosmetic result.

- Phthisis—unsightly, blind eye. The significant social, cosmetic, and

psychologic effects from a phthisical eye can be devastating to some

patients. With the use of a painted lens, these patients can resume

normal lifestyles. An opaque iris-painted lens with a black pupil offers

the best results. Iris color and diameter are selected to best match

the fellow eye.

- Amblyopia—therapeutic. Amblyopia therapy often fails only because

of the parent's inability to maintain the patch over the child's

eye. An occluder contact lens may be very successful because the

child is unable to remove the lens or “peek around it.” Psychologically, this

alternative can also be very advantageous.

- Aniridia and albinism—surgical or traumatic partial or total aniridia (Figs. 22 and 23). Patients with partial or total aniridia (congenital or acquired, surgical

or traumatic) may greatly benefit from an opaque iris-painted lens. If

the eye is sighted, a clear pupil is used, and the lens may also

have the refractive power incorporated into the lens for visual correction. A

clear lens may be used in the opposite eye if necessary and

so desired. In other cases, it may be necessary to have a black pupil

of the desired diameter to match the other eye.

Patients with albinism have often benefited from tinted lenses. The lenses

are used to decrease the photophobia caused by the iris transillumination. Some

patients need only a translucent lens whereas others require

an opaque iris-painted lens because of their severe photophobic symptoms. In

some patients (psychologic reasons) cosmesis is an important

factor to address.

- Photophobia—normal eyes that are abnormally light sensitive. These

patients, as well as individuals with pupillary abnormalities, corneal

pathology, and other anterior segment anomalies, also benefit from

tinted lenses.

As we review the numerous uses of contact lenses, cosmetic as well as therapeutic, rigid

and soft, we realize that contact lenses should always

be regarded as an integral part of all ophthalmologist's armamentarium

for total patient care. We should consider contact lenses not

just as a means to eliminate spectacle correction but also as a medical

device that can greatly improve quality of vision and quality of life. The

therapeutic uses of contact lenses are numerous and varied. It

is extremely rewarding, to both the patient and the ophthalmologist, to

be able to improve the quality of life of those patients we fit with

any of the specialty lenses.

Fig. 17. Posttrauma patient with resultant cosmetically unacceptable corneal scars. Fig. 17. Posttrauma patient with resultant cosmetically unacceptable corneal scars.

|

Fig. 18. Patient in Figure 17 fit with a soft, translucent iris-painted lens and black pupil. Fig. 18. Patient in Figure 17 fit with a soft, translucent iris-painted lens and black pupil.

|

Fig. 19. Young girl with iris melanoma surgically removed with resultant surgical

aniridia. Patient severely photophobic and self-conscious of cosmetic

appearance. Patient was successfully fit with an opaque iris-painted

lens with a clear pupil. Fig. 19. Young girl with iris melanoma surgically removed with resultant surgical

aniridia. Patient severely photophobic and self-conscious of cosmetic

appearance. Patient was successfully fit with an opaque iris-painted

lens with a clear pupil.

|

Fig. 20. Patient with traumatic cataract and total retinal detachment (leukocoria) resulting

from severe trauma. Fig. 20. Patient with traumatic cataract and total retinal detachment (leukocoria) resulting

from severe trauma.

|

Fig. 21. Patient from Figure 20 after fitting with very dark, translucent iris-painted lens with black

pupil. Fig. 21. Patient from Figure 20 after fitting with very dark, translucent iris-painted lens with black

pupil.

|

Fig. 22. Patient with traumatic aniridia (hockey puck injury) resulting in severely

photophobia and a cosmetically unacceptable eye. Fig. 22. Patient with traumatic aniridia (hockey puck injury) resulting in severely

photophobia and a cosmetically unacceptable eye.

|

Fig. 23. Patient from Figure 22 after fitting with a rigid, opaque iris-painted lens with clear pupil. Fig. 23. Patient from Figure 22 after fitting with a rigid, opaque iris-painted lens with clear pupil.

|

|