Dermoid and epidermoid cysts are choristomas arising from subcutaneous epidermal rests or epidermal tissues trapped along bony suture lines or within the diploe of the bone during embryonic development. The epidermal anlage develops into a cyst lined with stratified squamous epithelium, which is usually intimately associated with or firmly attached to the frontozygomatic suture superotemporally or to the maxillofrontal suture superonasally. Rarely, these cysts involve the suture confluence of the greater with of the sphenoid, zygoma, and frontal bones or the intradiploic space of the lateral orbital rim.6 If the cyst wall contains skin appendages, such as hair follicles, sweat glands or sebaceous glands, the cyst is termed a dermoid cyst. If skin appendages are absent, the cyst is termed an epidermoid cyst.7

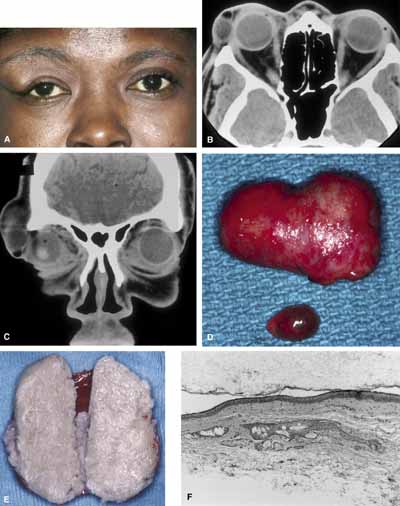

Typically, a dermoid cyst presents in a child as a mass protruding forward from beneath the superior orbital rim anterior to the orbital septum (Fig. 1). Dermoid cysts are found most commonly in the superotemporal quadrant and less frequently superonasally, but these cysts may occur elsewhere in the periobital region both anterior and posterior to the orbital septum and in the temporal fossa.

The usual cyst is a painless, smooth, ovoid-to-round, firm, rubbery mass. It may be mobile or immobile, being relatively free or firmly attached to the underlying bone (periosteum), but it is not attached to the overlying skin, distinguishing them from implantation cysts. Although contour abnormalities of the eyelid are common, there is little or no displacement of the globe with dermoid cysts located along the orbital rim. In an adult presentation, a dermoid cyst may frequently have a more posterior location.8 These posteriorly located cysts more typically present in adulthood, are more difficult to palpate, and proptosis and globe displacement are more common.

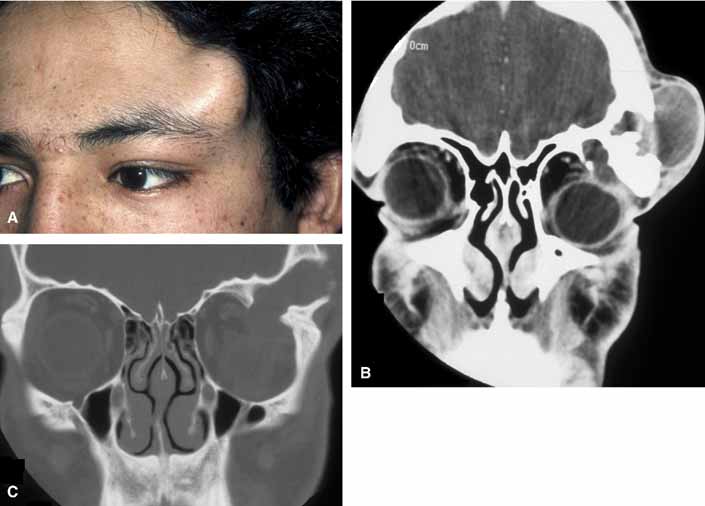

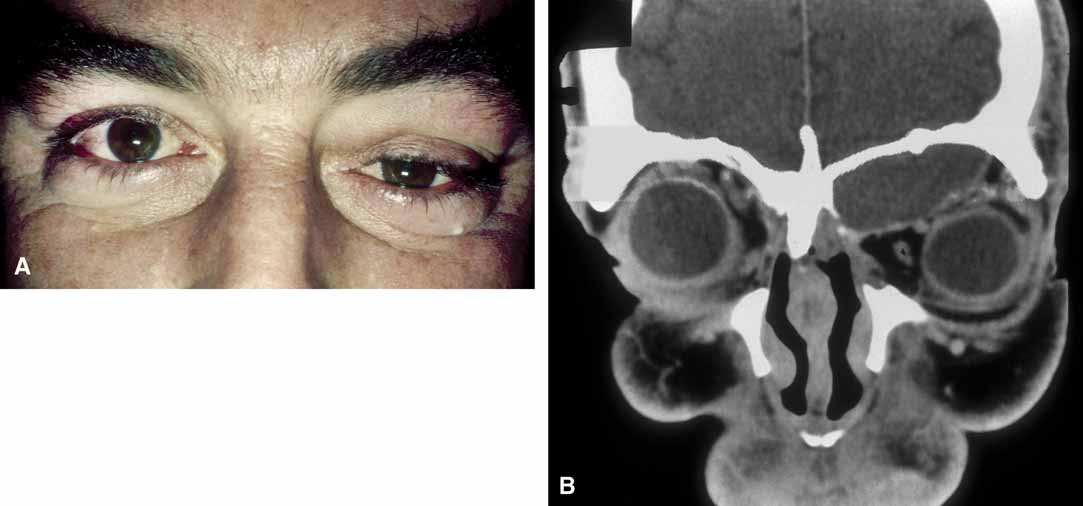

Rarely, an orbital cyst may pass through bony suture lines to extend intracranially or to the temporal fossa (Fig. 2).5,6 Pressure placed on the extracranial portion of a bilobed cyst may be transmitted through the bony dehiscence into the orbit, and is a cause for the mastication proptosis reported by Bullock and Bartley.9

The nature of an orbital dermoid cyst can be demonstrated well by computed tomography (CT): the cyst has a low-density lumen and its relationship to the underlying bone is often manifested by smooth remodeling of the bone secondary to cyst expansion; the high content of fatty material within the cyst makes it radiolucent.

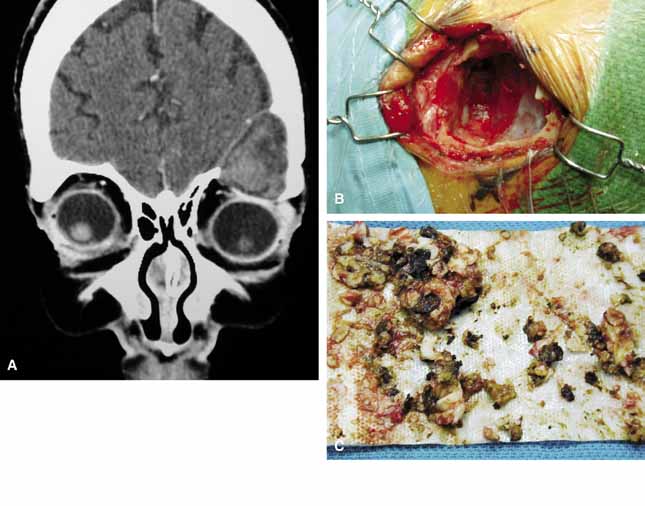

Because of the variable presentation of dermoid cysts, Shields et al.,5 have suggested a classification of orbital dermoid cysts by their association (or lack of association) with suture lines of the skull and assist the clinician in appropriate management. Cysts are classified as juxtasutural, sutural, or soft-tissue dermoid cysts. Those cysts adjacent to the bony suture line but not firmly attached are juxtasutural. A sutural dermoid cyst is firmly attached to bony sutures causing bone erosion, tunnels or an hourglass configuration. Soft tissue dermoid cysts may be strictly confined to soft tissues without any connection to a bone structure. Intradiploic epidermoid cysts are distinctly uncommon and were not included in Shields' classification (Fig. 3).

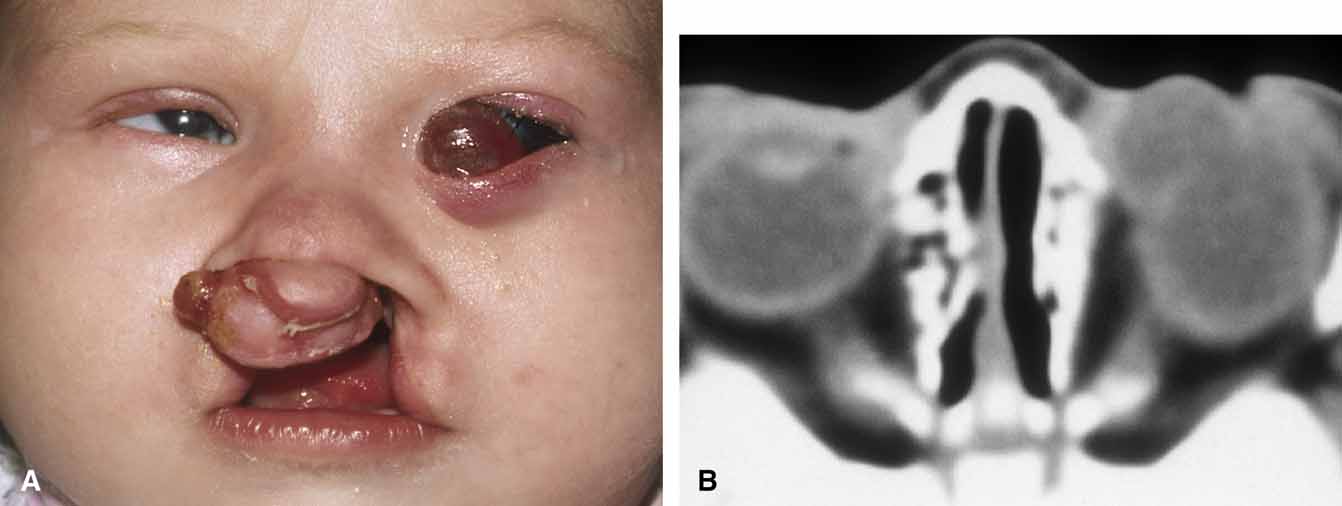

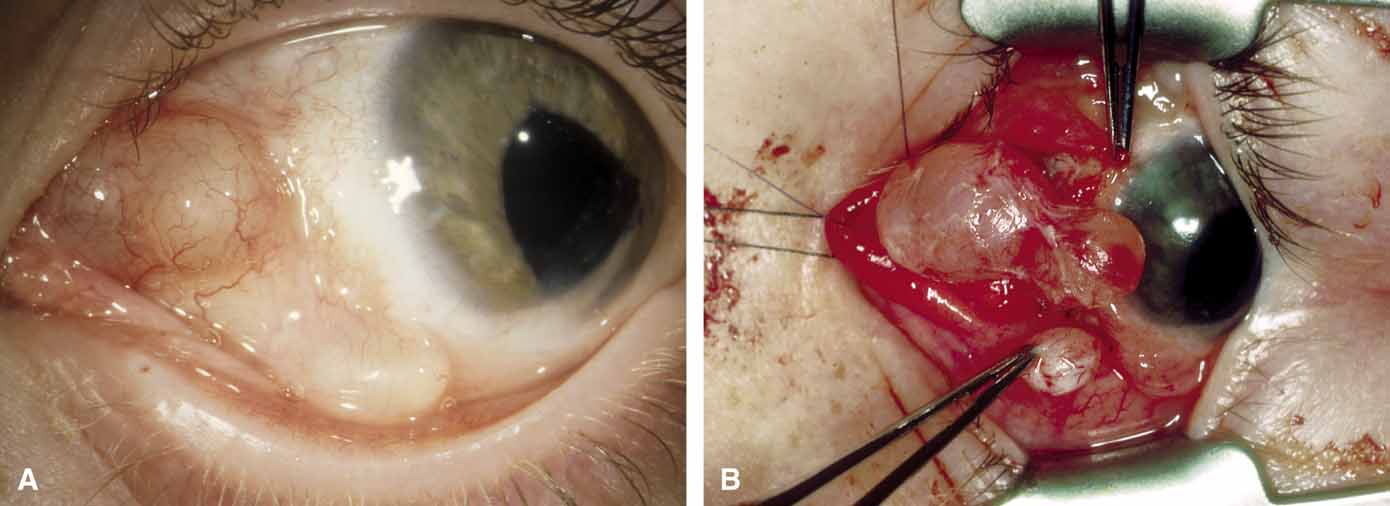

It is often cosmetic considerations that prompt the parents of an affected child to seek treatment. These cysts enlarge as the child grows and the possibility of accidental traumatic rupture is ever present. In adults, mass effect or periorbital inflammation due to leakage of cyst contents may prompt medical attention and surgical removal (Fig. 4).5,10

Surgical removal is the treatment of choice. The surgical approach is dictated by the location of the cyst and its association with boney suture lines. In the majority of juxtasutural dermoid cysts, the lesion can be reached through an incision placed directly over it. Because many of these cysts are located along the superior orbital rim, a brow incision may be placed directly over the cyst along the superior orbital rim. Because of a potentially visible scar, however, use of an upper eyelid crease incision has been advocated.11 A posteriorly located cyst (soft-tissue dermoid) or a bilobed cyst with transmission through the orbital rim (sutural dermoid), in contrast, requires more careful planning for an approach through an anterior and/or a lateral orbital route. Large intradiploic cysts and cysts located along the orbital roof and temporal fossa may require multidisciplines and approach transcranially or a temporal skull base approach.12,13

Surgical extirpation should be complete. Intraoperative rupture of the cyst with release of its contents into the orbit may incite a mild but smoldering granulomatous inflammation. The contents of these cysts may vary from an oily, tan liquid to a cheesy, yellow-white material. When inadvertent rupture occurs, the operating surgeon must flood the wound with irrigating solution to be sure that all this material has been washed away. Complete removal of the cyst wall is curative; incomplete removal may be followed by recurrence. Although marsupialization of deep and extensive dermoid cysts has been advocated by some practitioners,14 this technique is not recommended.8

Histologic study of all these cysts is recommended, because rare cases of epidermoid cysts undergoing malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma have been reported in adult patients.15 Although granulomatous inflammation may be seen histologically in as many as two-thirds of dermoid cysts removed in one large retrospective series, the clinical signs of inflammation are observed in the minority of patients.5,10