|

|

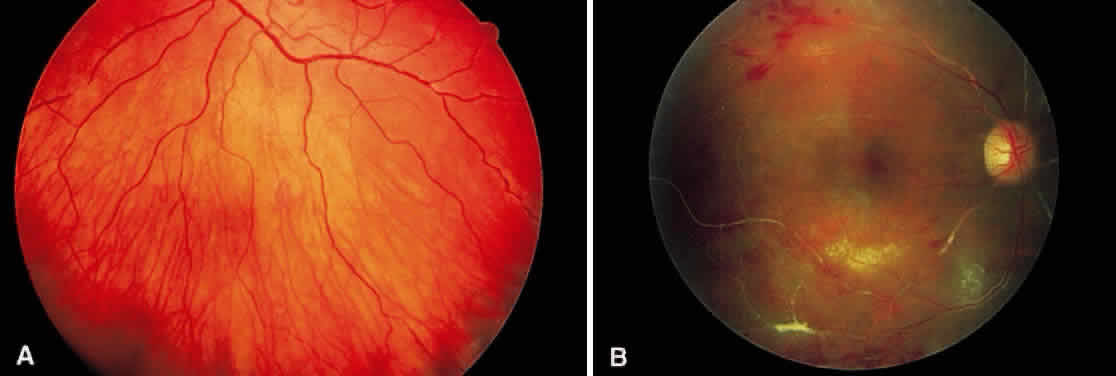

In the century since Henry Eales' observation of altered retinal veins, many investigators have described Eales' disease as a primary disease of altered retinal veins. Elliot and Harris suggest the term periphlebitis retinae for this disorder.4 However, recent reports suggest equal involvement of arteriolar and venular sheathing. Because of the evidence of arteriolar involvement (see Fig. 1B), this disease should be considered as a retinal vasculitis or vasculopathy. Others have used the term primary retinal perivasculitis.8 Cystoid macular edema, vitreal cells, keratic precipitates, and cell and flare in the anterior chamber have been observed in patients with Eales' disease.3

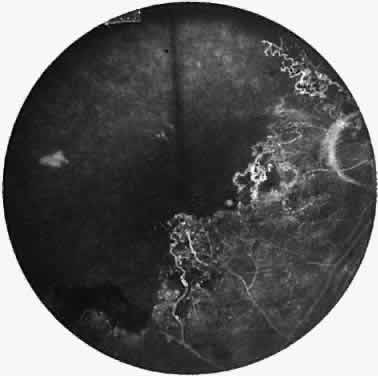

A varying degree of peripheral retinal nonperfusion is present in all patients with this disease. The nonperfusion generally is confluent and sharply demarcated from the posterior perfused retina (Fig. 3). Fine white lines representing the remains of obliterated large vessels (ghost vessels) often are seen in the area of nonperfusion. The temporal retina is most commonly affected.

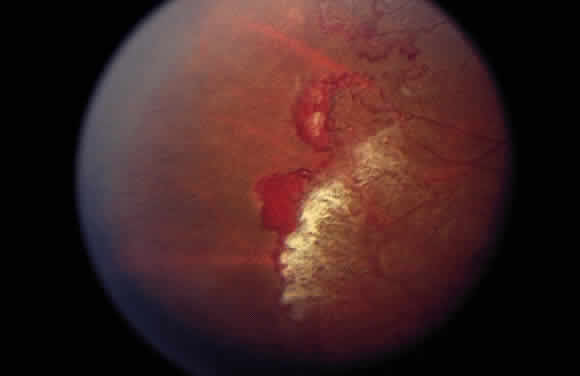

Elliot and Spitnas and colleagues have documented the abnormalities at the junction between the anteroperipheral nonperfused and the posterior perfused retina.9,10 Intraretinal hemorrhages often first appear in the affected area, followed by an increase in vascular tortuosity with frequent collateral formation around occluded vessels (see Fig. 3). Microaneurysms, arteriovenous shunts, and venous beading are commonly seen at the junction (Fig. 4). Fluorescein angiography enhances these abnormalities and often demonstrates staining at the stumps of obliterated vessels.

|

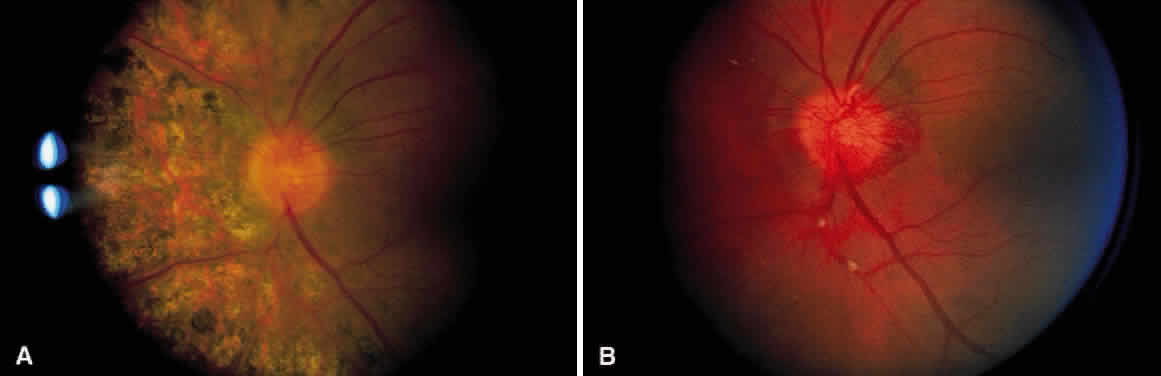

As a result of the retinal nonperfusion, new vessels can form either on the disc (neovascularization of the disc) or, more commonly, neovascularization can occur elsewhere in the retina (Fig. 5). These abnormal blood vessels can hemorrhage and are the major cause of visual loss in this disease. The neovascularization in the peripheral retina usually occurs at the junction of perfused and nonperfused retina, similar to the appearance of neovascularization in the peripheral retina in diabetic retinopathy and the other peripheral proliferative retinopathies. Neovascularization can be associated with extensive fibrovascular proliferation and fibrosis (Fig. 6). The anteroposterior and tangential traction resulting from the fibrovascular proliferation places these eyes at risk for development of retinal detachment. Neovascularization of the iris also has been described.

|