OBSERVATION

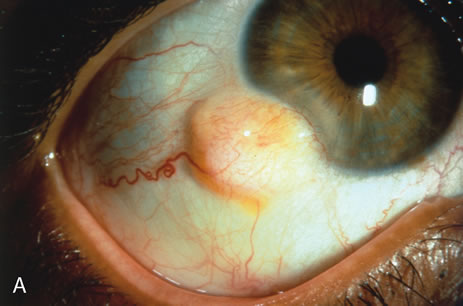

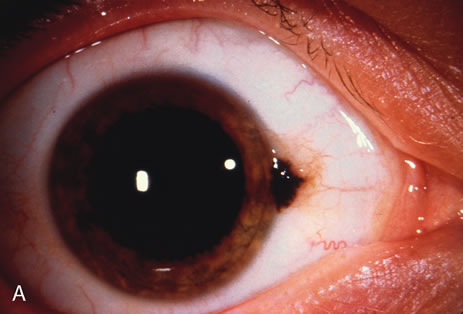

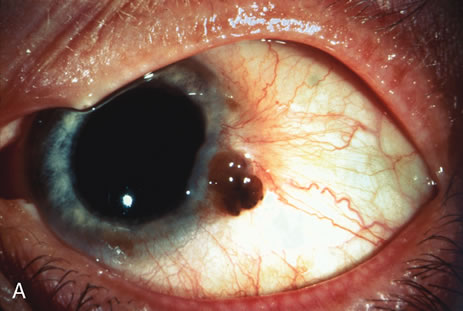

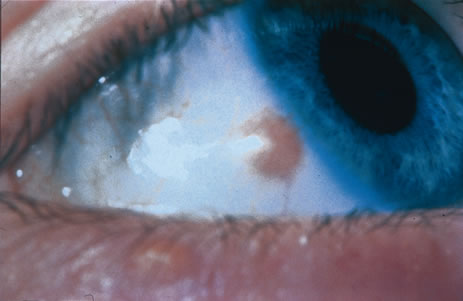

Observation is generally the management of choice for most benign, asymptomatic tumors of the conjunctiva. Selected examples of lesions that can be observed without interventional treatment include pinguecula, dermolipoma, and nevus. External or slit lamp photographs are advisable to document all lesions and are critical in following up suspicious lesions. Most patients are examined every 6 to 12 months for evidence of growth, malignant change, or secondary effects on normal surrounding tissues.

INCISIONAL BIOPSY

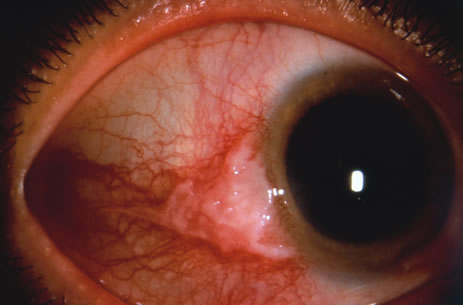

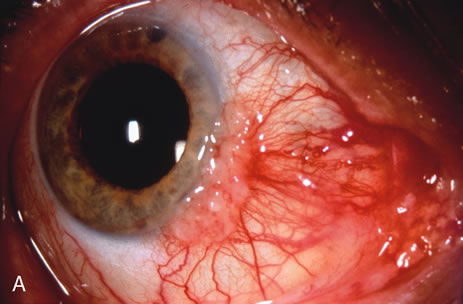

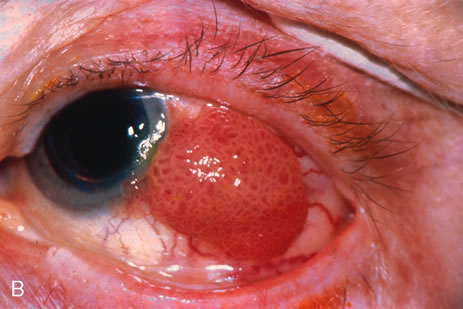

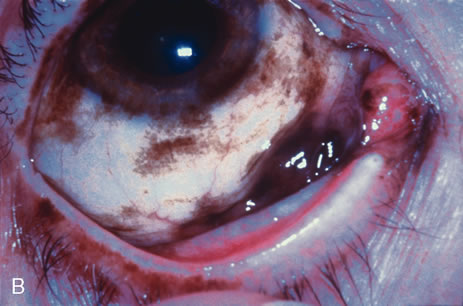

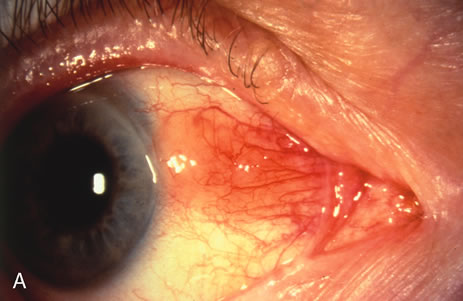

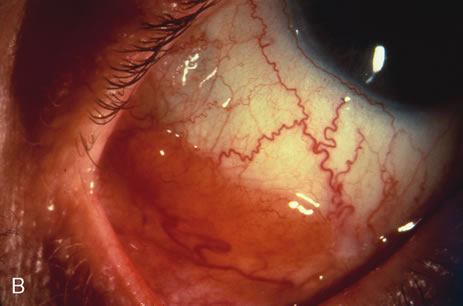

Incisional biopsy is reserved for extensive suspicious tumors that are symptomatic or suspected to be malignant. Examples include large squamous cell carcinoma, primary acquired melanosis (PAM), melanoma, and conjunctival invasion by sebaceous gland carcinoma. It should be understood that if such tumors occupy 4 clock hours or less on the bulbar conjunctiva, excisional biopsy is generally preferable to incisional biopsy. However, larger lesions can be approached by incisional wedge biopsy or punch biopsy. Further definitive therapy would then be planned based on the results of biopsy. Incisional biopsy is also appropriate for conditions that are ideally treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other topical medications. Such lesions include lymphoid tumors, metastatic tumors, extensive papillomatosis, and some cases of squamous cell carcinoma and PAM.

EXCISIONAL BIOPSY

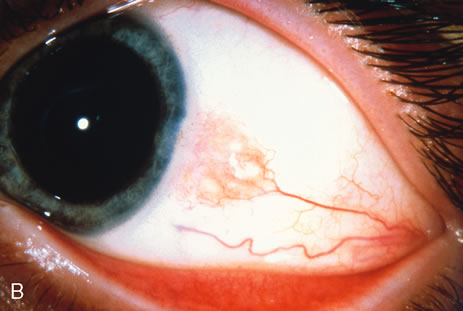

Primary excisional biopsy is appropriate for intermediate and small tumors that are symptomatic or suspected to be malignant. In such situations, excisional biopsy is preferred over incisional biopsy to avoid inadvertent tumor seeding. Examples of benign and malignant lesions that are ideally managed by excisional biopsy include symptomatic limbal dermoid, epibulbar osseous choristoma, steroid-resistant pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. When such lesions are located in the conjunctival fornix, they can be completely excised and the conjunctiva reconstructed primarily with absorbable sutures, sometimes with fornix-deepening sutures, or symblepharon ring to prevent adhesions. If the defect cannot be closed primarily, then a mucous membrane graft may be inserted.

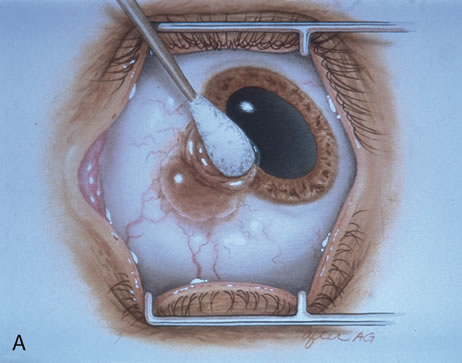

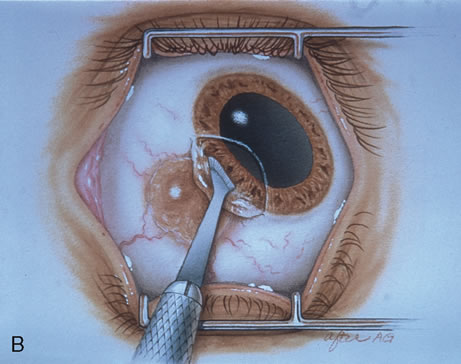

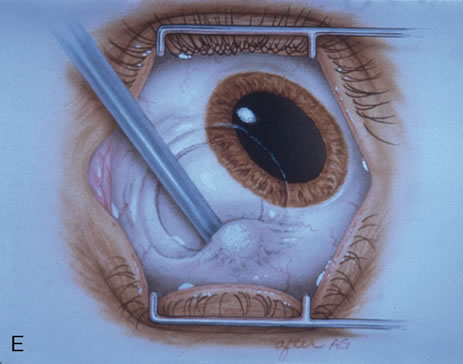

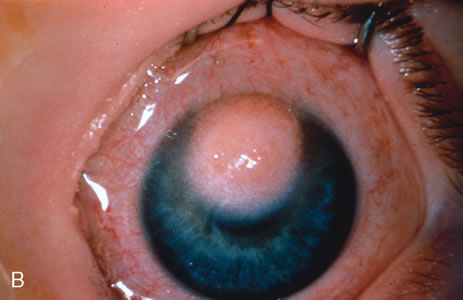

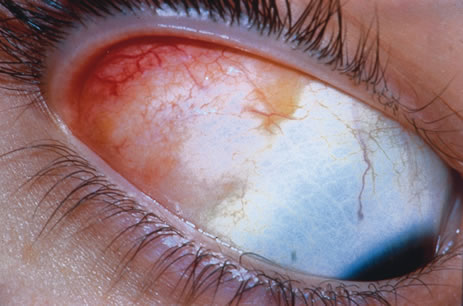

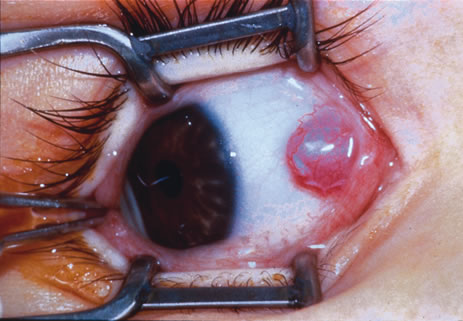

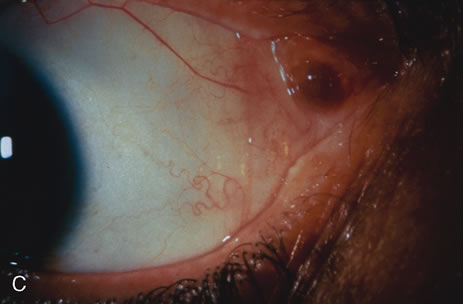

Most primary malignant tumors of the conjunctiva, such as squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma, arise in the interpalpebral area near the limbus, and the surgical technique for limbal tumors is different than that for forniceal tumors.4–6 Limbal neoplasms have a propensity to invade through the corneal epithelium and sclera into the anterior chamber and also through the soft tissues into the orbit. Thus, it is often necessary to remove a thin lamella of sclera to achieve tumor-free margins and to decrease the chance for tumor recurrence. In this regard, we employ a partial lamellar sclerokeratoconjunctivectomy with primary closure for such tumors (Fig. 1). Because cells from these friable tumors can seed into adjacent tissues, a gentle technique without touching the tumor (“no–touch” technique) is mandatory. Additionally, the surgery should be performed using microscopic technique and the operative field should be left dry so that cells adhere to the resected tissue. It is wise to avoid wetting the field with balanced salt solution until after the tumor is completely removed, to minimize seeding of cells.

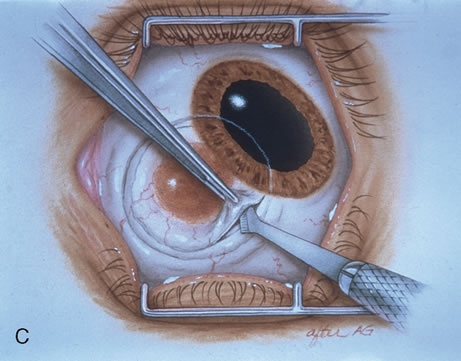

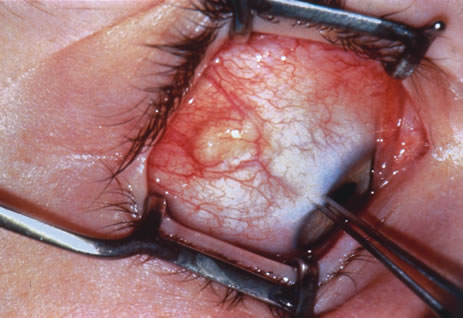

The technique for resection of limbal tumors is shown in Figure 1. Using retrobulbar anesthesia and the operating microscope, the corneal epithelial component is approached first and the conjunctival component is dissected second, with the goal of excising the entire specimen completely in one piece. Absolute alcohol soaked on an applicator is gently applied to the entire corneal component. This causes epithelial cellular devitalization and allows easier release of the tumor cells from Bowman's layer. A Beaver blade is used to microscopically outline the malignancy within the corneal epithelium using a delicate epithelial incision or epitheliorhexis technique 2 mm outside the corneal component. The Beaver blade is then used to sweep gently the affected corneal epithelium from the direction of the central cornea to the limbus, into a scroll that rests at the limbus. Next, a pentagonal or circular conjunctival incision based at the limbus is made 4 to 6 mm outside the tumor margin. The incision is carried through the underlying Tenon's fascia until the sclera is exposed so that full-thickness conjuctiva and Tenon's fascia is incorporated into the excisional biopsy. Cautery is applied to control bleeding. A second incision is then outlined by a superficial scleral groove approximately 0.2 mm in depth and 2.0 mm outside the base of the overlying adherent conjunctival mass. This groove is continued anteriorly to the limbus. The area outlined by the scleral groove is removed by flat dissection of 0.2 mm thickness within the sclera in an attempt to remove a superficial lamella of sclera, overlying Tenon's fascia and conjunctiva with tumor, and the scrolled corneal epithelium. In this way, the entire tumor with tumor-free margins is removed in one piece without touching the tumor itself. The removed specimen is then placed flatly on a piece of thin cardboard from the surgical tray and then placed in fixative and submitted for histopathologic studies. This step prevents the specimen from folding and allows better assessment of the tumor margins histopathologically. The used instruments are then replaced with fresh instruments for subsequent steps, to avoid contamination of healthy tissue with possible tumor cells.

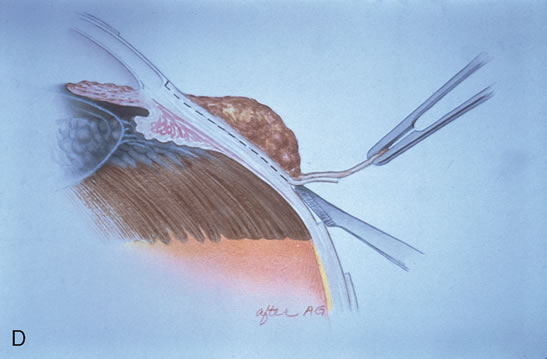

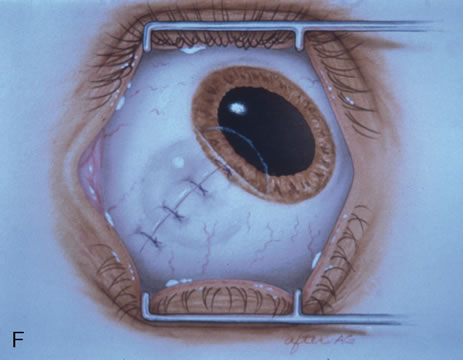

After excision of the specimen, cryotherapy is applied to the margins of the remaining bulbar conjunctiva. This is performed by freezing the surrounding bulbar conjunctiva as it is lifted away from the sclera using the cryoprobe. When the ice ball reaches a size of 4 to 5 mm, it is allowed to thaw, and the cycle is repeated once. The cryoprobe is then moved to an adjacent area of the conjunctiva, and the cycle is repeated until all of the margins have been treated by this method. It is not necessary to treat the corneal margins with cryoapplication. The tumor bed is treated with absolute alcohol wash on cotton tip applicator and bipolar cautery, avoiding cryotherapy directly to the sclera.

Using clean instruments, the conjunctiva is mobilized for closure of the defect by loosening the intermuscular septum with Steven's scissor spreading and creating transpositional conjunctival flaps. Closure is completed with interrupted absorbable 6-0 or 7-0 sutures. If the surgeon prefers, an area of bare sclera may be left near the limbus; however, we prefer complete closure because it promotes better healing and allows for facility of further surgery if recurrence develops. The patient is treated with topical antibiotics and corticosteroids for 2 weeks, then followed at 3- to 6-month intervals.

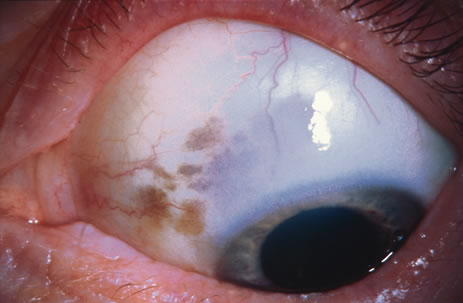

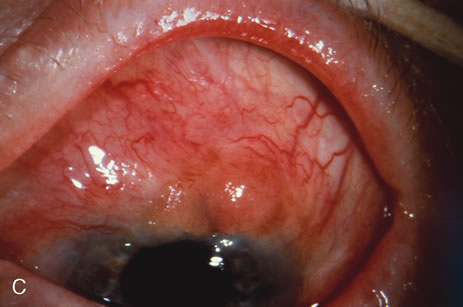

CRYOTHERAPY

In the management of conjunctival tumors, cryotherapy may be used as a supplemental treatment to excisional biopsy as described above. In such cases, it can eliminate microscopic tumor cells and prevent recurrence of malignant tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. It can also be used as a principal treatment for PAM and pagetoid invasion of sebaceous gland carcinoma. If cryotherapy can devitalize the malignant or potentially malignant cells in such instances, radical surgery, such as orbital exenteration, can often be delayed or avoided.

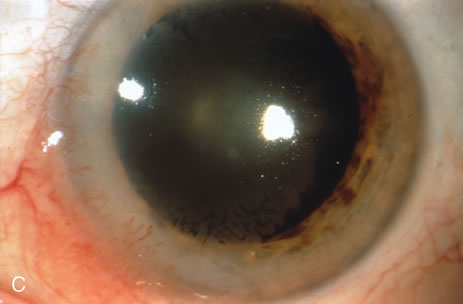

CHEMOTHERAPY

Recent evidence has revealed that topical eye drops containing mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil, or interferon are effective in treating epithelial malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma, PAM, and pagetoid invasion of sebaceous gland carcinoma.10–18 Mitomycin C or 5-fluorouracil is employed most successfully for squamous cell carcinoma, especially after tumor recurrence following previous surgery. This medication is prescribed in a topical dosage four times daily for a 1-week period, followed by a 1-week hiatus to allow the ocular surface to recover (Table 1). This cycle is repeated once again, so most patients receive a total of 2 weeks of the chemotherapy. Both mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil are most effective for squamous cell carcinoma and less effective for PAM and pagetoid invasion of sebaceous gland carcinoma. Toxicities include most commonly dry eye findings, superficial punctate epitheliopathy, and punctal stenosis. Corneal melt, scleral melt, and cataract may develop if these agents are used in the presence of open conjunctival wounds or used excessively. Topical interferon can be effective for squamous epithelial malignancies and is less toxic to the surface epithelium, but this medication may require many months of use to effect a result.

Table 1. Protocol for Use of Mitomycin C for Conjunctival Squamous Cell

Neoplasia and Primary Acquired Melanosis

| Week | Protocol |

| 1 | Slit lamp biomicroscopy |

| Place upper and lower punctal plugs | |

| Cycle 1: mitomycin C 0.04% q.i.d. to the affected eye | |

| 2 | No medication |

| 3 | Cycle 2: mitomycin C 0.04% q.i.d. to the affected eye |

| 4 | No medication |

| Slit lamp biomicroscopy | |

| Prescribe more cycles if residual tumor exists | |

| Remove punctal plugs after all medication complete |

RADIOTHERAPY

Two forms of radiotherapy are employed for conjunctival tumors, namely, external beam radiotherapy and custom-designed plaque radiotherapy. External beam radiotherapy to a total dose of 3000 to 4000 centigray (cGy) is used to treat conjunctival lymphoma and metastatic carcinoma when such lesions are too large or diffuse to excise locally. Side effects of dry eye, punctate epithelial abnormalities, and cataract should be anticipated.

Custom-designed plaque radiotherapy19 to a dose of 3000 to 4000 cGy can be used to treat conjunctival lymphoma or metastasis. A higher dose of 6000 to 8000 cGy can be employed to treat the more radiation-resistant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma. In general, plaque radiotherapy is reserved for those patients who have diffuse tumors that are incompletely resected and for those who display multiple recurrences. There are two design choices for conjunctival custom plaque radiotherapy: a conformer plaque technique with six fractionated treatment sessions on an outpatient basis, or a reverse plaque technique with the device sutured onto the episcleral in an inpatient setting. In unique instances, plaque radiotherapy to a low dose of 2000 cGy is employed for benign conditions, such as steroid-resistant pyogenic granuloma, that show recurrence after surgical resection.20 Such treatment should be performed by experienced radiation oncologists and ocular oncologists.

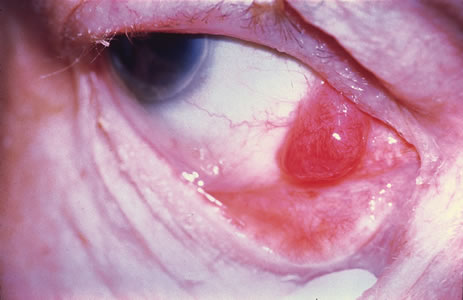

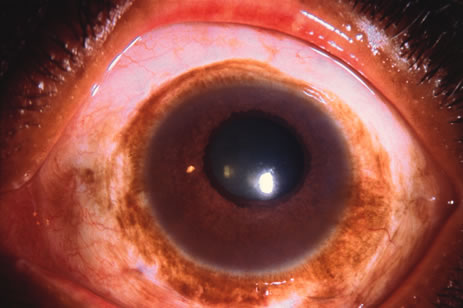

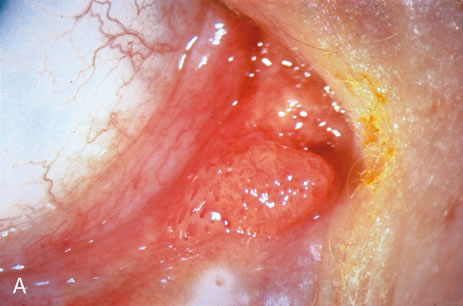

MODIFIED ENUCLEATION

Modified enucleation is a treatment option for primary malignant tumors of the conjunctiva that have invaded through the limbal tissues into the globe, producing secondary glaucoma. Such an occurrence is quite rare but can occasionally occur with squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. The uncommon mucoepidermoid variant of squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva has a greater tendency for such invasion.21,22 At the time of enucleation, it is necessary to remove the involved conjunctiva intact with the globe to avoid spreading tumor cells. Thus, the initial peritomy should begin at the limbus, but when the tumor is approached, the incision should proceed posteriorly from the limbus to surround the tumor-affected tissue by at least 3 to 4 mm. The tumor will remain adherent to the globe at the limbus. Occasionally, a suture is employed through the surrounding conjunctiva into the episclera to secure the tumor to the globe so that it will not be displaced during subsequent manipulation. The remaining steps of enucleation are gently performed, and the globe is removed with tumor adherent after cutting the optic nerve from the nasal side. The margins of the remaining, presumed unaffected conjunctiva are treated with double freeze-thaw cryotherapy. Often this surgical technique leaves the patient with a limited amount of residual unaffected conjunctiva for closure. In these instances, a mucous membrane graft or amniotic membrane graft may be necessary for adequate closure and to provide fornices for a prosthesis. In some instances, a simple horizontal inferior forniceal conjunctival incision from canthus to canthus may suffice, as long as the conformer is constantly worn as a template, so the new conjunctival fornix grows deep and around this structure.

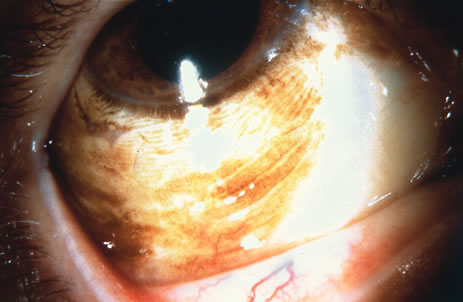

ORBITAL EXENTERATION

Orbital exenteration is probably the treatment of choice for primary malignant conjunctival tumors that have invaded the orbit or that exhibit complete involvement of the conjunctiva.7,23,24 Either an eyelid-removing or eyelid-sparing exenteration is employed, depending on the extent of eyelid involvement. The eyelid-sparing technique is preferred because the patients have better cosmetic appearance and heal within 2 or 3 weeks. Specifically, if the anterior lamella of the eyelid is uninvolved with tumor, an eyelid-sparing (eyelid-splitting) exenteration may be accomplished.4,7,24

MUCOUS MEMBRANE GRAFT

Mucous membrane grafts are occasionally necessary to replace vital conjunctival tissue after removal of extensive conjunctival tumors. The best donor sites include the forniceal conjunctiva of the ipsilateral or contralateral eye and buccal mucosa from the posterior aspect of the lower lip or lateral aspect of the mouth. Such grafts are usually removed by a freehand technique, fashioned to fit the defect, and secured into place with cardinal and running absorbable 6-0 or 7-0 sutures. Currently, in most instances, we employ a donor amniotic membrane graft to replace lost conjunctiva.8,9 The tissue is delivered frozen and must be defrosted for 20 minutes. The fine, transparent material is carefully peeled off its cardboard surface, laid basement membrane side up, and sutured into place with absorbable sutures. Topical antibiotic and steroid ointments are applied following all conjunctival grafting procedures.

It is important that the surgeon use a minimal manipulation technique for tumor resection. For graft harvest and placement, the surgeon should always use clean, sterile instruments at both the donor and the recipient sites. Free tumor cells can rest on instrument tips and later implant and grow in previously uninvolved areas if such precautions are not taken.