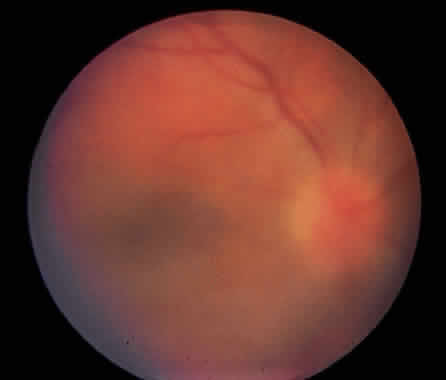

There are no pathognomonic features of syphilitic uveitis. Iridocyclitis in early disease may be unilateral and severe. In late tertiary syphilis, iridocyclitis may also be unilateral and appear 4 to 6 months after inadequate treatment of tertiary syphilis. Syphilitic chorioretinitis also has no pathognomonic features. There may be multifocal chorioretinal infiltrates, overlying vitritis, and papillitis.19 Early findings include vitritis (Fig. 1), multifocal chorioretinitis (Fig. 2), optic neuritis, retinal vasculitis, retinal hemorrhages, and retinal edema. Pigment proliferation is present late in the course of the disease (Fig. 3). Presenting complaints in patients with acute syphilitic uveitis include blurred vision, pain, redness, photophobia, and floating spots. Ocular involvement may be unilateral or bilateral, and acute or chronic. Syphilitic uveitis may be described as a panuveitis, but frequently the anatomic terms iritis, iridocyclitis, vitritis, chorioretinitis, and retinal vasculitis are appropriate, depending on which part of the eye appears to be involved primarily.

The differential diagnosis of syphilitic uveitis when iritis is the primary presentation includes the HLA-B27 positive syndromes. When more posterior involvement is present, with vitreous cells and active retinitis, several entities must be considered (Table 2). History and laboratory studies are helpful in the differentiation. Cytomegalovirus infection may coexist with syphilitic infection in the patient with AIDS and must be considered as a cause of inflammation in any patient immunosuppressed for whatever reason. Syphilis is more rapidly progressive in HIV-infected patients.20 In these patients, dense vitritis may be the presenting ocular abnormality.21 Toxoplasmosis can be differentiated by the presence of a compatible lesion and a positive Toxoplasma titer. Candida endophthalmitis may coexist with syphilis in an intravenous drug abuser. Behçet's disease may be difficult to rule out clinically, especially when there is oral or genital ulceration, but HLA typing may be helpful. Sarcoidosis must be considered in any differential diagnosis of posterior uveitis, but it is less likely if levels of angiotensin converting enzyme and serum lysozyme and the chest radiograph are normal. Intraocular lym phoma (reticulum cell sarcoma) should be considered in the elderly patient with vitreous cell. Intraocular lymphoma may be diagnosed by cytologic examination of the vitreous. The problem is that syphilis may be present even when there are other causes of uveitis. If tests for syphilis are positive, the patient should be treated for syphilis, even when the patient has other likely sources of inflammation.

TABLE 2 Differential Diagnosis of Posterior Syphilitic Uveitis

Cytomegalovirus retinitis

Toxoplasmosis

Candida endophthalmitis

Behcet's disease

Sarcoidosis

Intraocular lymphoma (reticulum cell sarcoma)