1. Lerner PI, Weinstein L: Infective endocarditis in the antibiotic era. N Engl J Med 274:388, 1966 2. Finland M, Barnes MW: Changing etiology of bacterial endocarditis in the antibacterial era. Experiences

at Boston City Hospital 1933–1965. Ann Intern Med 72:341, 1970 3. Garvey GJ, Neu HC: Infective endocarditis—an evolving disease. A review of endocarditis

at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, 1968–1973. Medicine (Balt) 57:105, 1978 4. Bayliss R, Clarke C, Oakley CM, et al: The microbiology and pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. Br Heart J 50:513, 1983 5. El-Khatib MR, Wilson FM, Lerner AM: Characteristics of bacterial endocarditis in heroin addicts in Detroit. Am J Med Sci 271:197, 1976 6. Stimmel B, Donoso E, Dack S: Comparison of infective endocarditis in drug addicts and nondrug users. Am J Cardiol 32:924, 1973 7. Reisberg BE: Infective endocarditis in the narcotic addict. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 22:193, 1979 8. Castillo JC, Anguita MP, Torres F, et al: Long-term prognosis of early and late prosthetic valve endocarditis. Am J Cardiol 93:1185, 2004 9. Akowuah EF, Davies W, Oliver S, et al: Prosthetic valve endocarditis: Early and late outcome following medical

or surgical treatment. Heart 89:269, 2003 10. Angrist AA, Oka M: Pathogenesis of bacterial endocarditis. JAMA 183:249, 1963 11. Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB: Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med 345:1318, 2001 12. Shively BK, Gurule FT, Roldan CA, et al: Diagnostic value of transesophageal compared with transthoracic echocardiography

in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 18:391, 1991 13. Werner GS, Schulz R, Fuchs JB, et al: Infective endocarditis in the elderly in the era of transesophageal echocardiography: Clinical

features and prognosis compared with younger patients. Am J Med 100:90, 1996 14. Weinstein L, Rubin RH: Infective endocarditis—1973. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 16:239, 1973 15. Jones HR Jr, Siekert RG, Geraci JE: Neurologic manifestations of bacterial endocarditis. Ann Intern Med 71:21, 1969 16. Ziment I: Nervous system complications in bacterial endocarditis. Am J Med 47:593, 1969 17. Pruitt AA, Rubin RH, Karchmer AW, Duncan GW: Neurologic complications of bacterial endocarditis. Medicine (Balt) 57:329, 1978 18. Roder BL, Wandall DA, Espersen F, et al: Neurologic manifestations in Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: A review of 260 bacteremic cases in nondrug addicts. Am J Med 102:379, 1997 19. Eishi K, Kawazoe K, Kuriyama Y, et al: Surgical management of infective endocarditis associated with cerebral

complications. Multi-center retrospective study in Japan. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 110:1745, 1995 20. Heiro M, Nikoskelainen J, Engblom E, et al: Neurologic manifestations of infective endocarditis: A 17-year experience

in a teaching hospital in Finland. Arch Intern Med 160:2781, 2000 21. Ramonas KM, Freilich BD: Iris abscess as an unusual presentation of endogenous endophthalmitis in

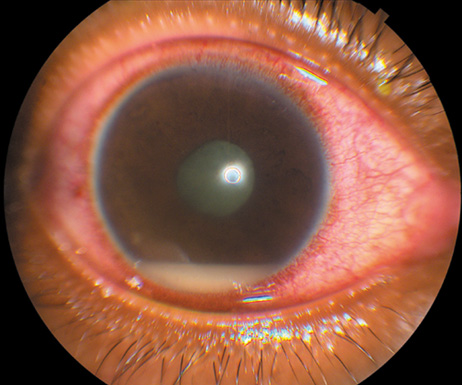

a patient with bacterial endocarditis. Am J Ophthalmol 135:228, 2003 22. Kennedy JE, Wise GN: Clinicopathological correlation of retinal lesions. Subacute bacterial

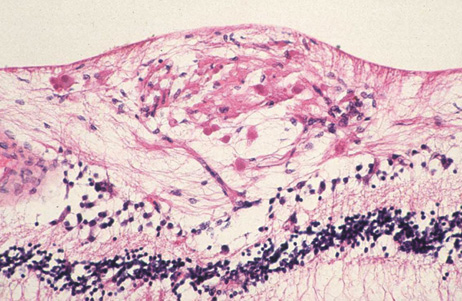

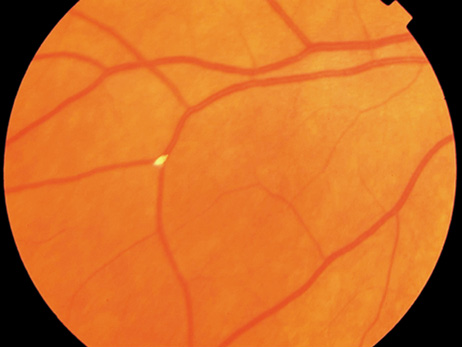

endocarditis. Arch Ophthalmol 74:658, 1965 23. Burns CL: Bilateral endophthalmitis in acute bacterial endocarditis. Am J Ophthalmol 88:909, 1979 24. Treister G, Rothkoff L, Yalon M, et al: Bilateral blindness following panophthalmitis in a case of bacterial endocarditis. Ann Ophthalmol 14:663, 1982 25. Yanoff M, Fine BS: Neural (sensory) retina. In Ocular Pathology. Philadelphia: Mosby-Wolfe, 1996:376 26. Hermans PE: The clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis. Mayo Clin Proc 57:15, 1982 27. Brown GC, Magargal LE, Shields JA, et al: Retinal arterial obstruction in children and young adults. Ophthalmology 88:18, 1981 28. Munier F, Othenin-Girard P: Subretinal neovascularization secondary to choroidal septic metastasis

from acute bacterial endocarditis. Retina 12:108, 1992 29. Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR: Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: A 17-year prospective series and

review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol 48:403, 2003 30. Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, et al: Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Report of a ten-year retrospective

study. Ophthalmology 101:832, 1994 31. Christensen SR, Hansen AB, La CM, Fledelius HC: Bilateral endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: A report of four cases. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 82:306, 2004 32. Lopez JA, Ross RS, Fishbein MC, Siegel RJ: Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: A review. Am Heart J 113:773, 1987 33. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J: The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med 346:752, 2002 34. Dickens P, Chan AC: Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in Hong Kong Chinese. Arch Pathol Lab Med 115:359, 1991 35. Schoen F: The heart. In Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005:598 36. Eiken PW, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, et al: Surgical pathology of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in 30 patients, 1985–2000. Mayo Clin Proc 76:1204, 2001 37. Anderson D, Bell D, Lodge R, Grant E: Recurrent cerebral ischemia and mitral valve vegetation in a patient with

antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol 14:839, 1987 38. Geyer SJ, Franzini DA: Myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve complicated by nonbacterial

thrombotic endocarditis with systemic embolization. Am J Clin Pathol 72:489, 1979 39. Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Gray F, Brunet P: Infarcts of both inferior parietal lobules with impairment of visually

guided eye movements, peripheral visual inattention and optic ataxia. Brain 109:81, 1986 40. Jeresaty RM: Sudden death in the mitral valve prolapse-click syndrome. Am J Cardiol 37:317, 1976 41. Jeresaty RM: Mitral valve prolapse. An update. JAMA 254:793, 1985 42. Devereux RB: Mitral valve prolapse. J Am Med Women's Assoc 49:192, 1994 43. Procacci PM, Savran SV, Schreiter SL, Bryson AL: Prevalence of clinical mitral-valve prolapse in 1169 young women. N Engl J Med 294:1086, 1976 44. Markiewicz W, Stoner J, London E, et al: Mitral valve prolapse in one hundred presumably healthy young females. Circulation 53:464, 1976 45. Freed LA, Levy D, Levine RA, et al: Prevalence and clinical outcome of mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med 341:1, 1999 46. Devereux RB, Hawkins I, Kramer-Fox R, et al: Complications of mitral valve prolapse. Disproportionate occurrence in

men and older patients. Am J Med 81:751, 1986 47. O'Rourke RA, Crawford MH: The systolic click-murmur syndrome: Clinical recognition and management. Curr Probl Cardiol 1:1, 1976 48. Pyeritz RE, Wappel MA: Mitral valve dysfunction in the Marfan syndrome. Clinical and echocardiographic

study of prevalence and natural history. Am J Med 74:797, 1983 49. Olsen EG, Al-Rufaie HK: The floppy mitral valve. Study on pathogenesis. Br Heart J 44:674, 1980 50. Whittaker P, Boughner DR, Perkins DG, Canham PB: Quantitative structural analysis of collagen in chordae tendineae and its

relation to floppy mitral valves and proteoglycan infiltration. Br Heart J 57:264, 1987 51. Davies MJ, Moore BP, Braimbridge MV: The floppy mitral valve. Study of incidence, pathology, and complications

in surgical, necropsy, and forensic material. Br Heart J 40:468, 1978 52. Braunwald E: Valvular heart disease. In Heart Disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001:1665 53. Freed LA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, et al: Mitral valve prolapse in the general population: The benign nature of echocardiographic

features in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 40:1298, 2002 54. Langholz D, Mackin WJ, Wallis DE, et al: Transesophageal echocardiographic assessment of systolic mitral leaflet

displacement among patients with mitral valve prolapse. Am Heart J 135:197, 1998 55. Lesser RL, Heinemann MH, Borkowski H Jr, Cohen LS: Mitral valve prolapse and amaurosis fugax. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1:153, 1981 56. Seelenfreund MH, Silverstone BZ, Hirsch I, Rosenmann D: Mitral valve prolapse (Barlow's syndrome) and retinal emboli. Metab Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol 11:119, 1988 57. Hopkins A, Yiannikas J, Francis IC: Mitral valve prolapse and retinal infarction. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol 15:79, 1987 58. Lichter H, Loya N, Sagie A, et al: Keratoconus and mitral valve prolapse. Am J Ophthalmol 129:667, 2000 59. Street DA, Vinokur ET, Waring GO III, et al: Lack of association between keratoconus, mitral valve prolapse, and joint

hypermobility. Ophthalmology 98:170, 1991 60. Traboulsi EI, Aswad MI, Jalkh AE, Malouf JF: Ocular findings in mitral valve prolapse syndrome. Ann Ophthalmol 19:354, 1987 61. Ross RS, McKusick VA: Aortic arch syndromes; diminished or absent pulses in arteries arising

from arch of aorta. AMA Arch Intern Med 92:701, 1953 62. Kahn M, Knox DL, Green WR: Clinicopathologic studies of a case of aortic arch syndrome. Retina 6:228, 1986 63. Tour RL, Hoyt WF: The syndrome of the aortic arch: ocular manifestations of pulseless disease

and a report of a surgically treated case. Am J Ophthalmol 47:35, 1959 64. Schmidt MH, Fox AJ, Nicolle DA: Bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy as a presentation of Takayasu's

disease. J Neuroophthalmol 17:156, 1997 65. Chun YS, Park SJ, Park IK, et al: The clinical and ocular manifestations of Takayasu arteritis. Retina 21:132, 2001 |