ANTERIOR UVEA

Cancer to the iris and ciliary body accounts for 4% to 11%10,11,24–26 of intraocular metastasis. Patients with cancer metastatic to the ciliary body and angle structures usually have associated injected epibulbar vessels and anterior uveitis. An iris metastasis is typically a yellow, gelatinous mass located within the iris stroma. Rarely, the iris tumor may be friable and may seed into the aqueous, producing a pseudohypopyon composed of tumor cells8 (Fig. 1). Other associated finding in those eyes with metastases to the anterior uvea include ocular hypertension, hyphema, uveitis, rubeosis, cataract, and infiltration into the surrounding structures.8,24–26 The differential diagnosis of cancer metastatic to the iris includes amelanotic melanoma, granulomatous uveitis, iris cysts, retained foreign body, and retinoblastoma in children.8,26

|

CHOROID

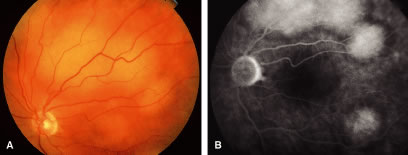

The choroid is the most common site of carcinoma metastatic to the eye (88% of eyes).6,7,10,11 Patients with choroidal metastasis usually complain of painless vision or visual field loss. About 47% of the choroidal lesions were temporal to the disc.11 Metastatic cancer to the eye was multifocal in the choroid in 28% of the eyes.11 Breast cancer was more commonly bilateral (33%) and multifocal (32%) compared with other primary neoplasms.11 There is an associated nonrhegmatogenous retinal detachment in 73% of the eyes.11 Carcinoma metastatic to the choroid is typically a placoid or dome-shaped yellow tumor of varying diameter and thickness. Multiple lesions are not infrequent (Fig. 2). The mean thickness in our series was 3 mm. Rarely a rip to the retinal pigment epithelium can develop.27 Regressed lesions are relatively flat with overlying pigment and lack of associated subretinal fluid. The differential diagnosis of choroidal metastases include amelanotic malignant melanoma, amelanotic nevus, choroidal hemangioma, choroidal osteoma, posterior scleritis, uveal effusion syndrome, Harada's disease, and central serous choroidopathy.28

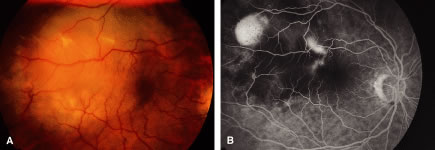

OPTIC DISC

Metastatic cancer to the optic disc is rare (4.5% intraocular metastases).29 The optic disc is usually affected by direct extension of an adjacent choroidal metastatic tumor that infiltrates the optic disc (Fig. 3). Occasionally, tumor emboli enter the optic disc by hematogenous or intrathecal invasion (meningeal carcinomatosis). There is an adjacent juxtapapillary choroidal lesion in 74% of eyes.29 The associated findings include optic disc edema, venous stasis, an afferent pupillary defect, and less commonly hemorrhage or obstruction of a retinal artery or vein.8,29 The optic disc appears to be edematous, hyperemic, or atrophic in patients with meningeal carcinomatosis involving the optic nerve sheath.2,10,29 Most cases are from breast, lung, or an unknown primary malignancy. The differential diagnosis includes papilledema, optic neuritis, granuloma, optic disc drusen, and capillary hemangioma.8

|

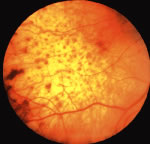

RETINA

Metastatic cancer to the retina, which has rarely been reported,8,13 reaches the retina by either direct invasion from the adjacent choroid or by tumor emboli through the central retinal artery. The retinal tumors may appear as patchy yellow lesions associated with hemorrhage or exudate.

Sometimes there are overlying clumps of tumor cells in the vitreous such as in cases of cutaneous melanoma metastatic to the retina. The differential diagnosis includes cotton-wool spots, vascular obstructions, and retinitis.

VITREOUS

Metastatic cancer to the vitreous can be associated with metastasis to the retina or ciliary body.8,30 Clumps of tumor cells are visible in the vitreous. Cutaneous malignant melanoma and lymphoproliferative disorders such as large cell lymphoma are known to disseminate to the vitreous, although breast cancer and lung cancer have been associated with metastatic cells in the vitreous cavity. The differential diagnosis includes primary ocular lymphoma, vitritis, and other vitreous opacities.