THE BATTERED CHILD: SYSTEMIC MANIFESTATIONS

The battered child syndrome refers to bruises, lacerations, fractures, burns, intra-abdominal trauma, blunt head injury, and other forms of physical abuse. The possibility of child abuse should be considered whenever there is wide discrepancy between the explanation for the child's condition, and the physical findings (Table 1). For example, an accidental fall from a couch or bed is a common household occurrence, but serious injury is extremely unlikely. A parent may state that the child fell against a table. On examination, however, the child is found to be covered with multiple bruises. Another clue is inconsistency of the degree of injury with the developmental skills of a child. For example, falling off a tricycle at age 1 year when a child is unable to ride a tricycle is a doubtful explanation for a child's injury. Bruising of almost any kind in the first few months of life is worrisome. Histories that change repeatedly on inquiry from different members of the health-care team or new explanations that seem to arise only after a mechanism for injury is suggested should also be considered suspect. A careful history or subsequent investigation may reveal that the child has been treated at different hospitals for a series of injuries of varying severity.

Table 1. Diagnostic Features of the Battered Child Syndrome

- Fractures and soft tissue injury in different stages of healing with no

organic cause

- Disproportionate degree of injury as compared to history

- Reported mechanism of injury incompatible with physical findings

- Multiple admissions to different hospitals for injuries

- No fresh lesions during hospitalization

- Unexplained delay in seeking care

Modified from Harcourt B: The role of the ophthalmologist in thediagnosis and management of child abuse. Ophthal Surg 4:37, 1973.

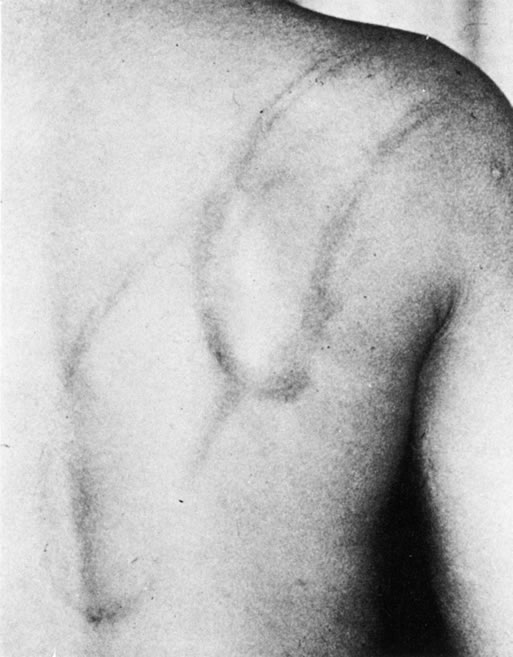

Physical examination may provide additional clinical evidence of child abuse (Table 2). Of course, accidental bruising and abrasion is part of normal childhood but these injuries are usually confined to the knees, anterior surface of the lower legs, the face, and other exposed areas. Accidental injuries do not follow artificial nonbiologic patterns, usually have a viable clear explanation, and are appropriate for the child's developmental level. Bruises that are found on certain parts of the body should raise the possibility of child abuse (Figs. 1 and 2). Bruises that predominate on the buttocks and lower back are often related to punishment (Fig. 3). Likewise, the abdomen and the back of the arms and legs are unusual sites for accidental injuries. Bruises can be morphologically similar to the implement used to inflict the trauma (Fig. 4).11,12 For example, the imprint of a belt buckle or hand may be seen clearly on a child's skin. Genital or innerthigh bruises may be the result of punishment for toileting mishaps. Bruises and scars at multiple stages of healing imply repeated abuse.

Table 2. Physical Manifestations of the Battered Child Syndrome

Brain injury or intracranial hemorrhage from blunt trauma

Bruises in different stages of healing with patterns and distribution inconsistent

with accidental causation

Pattern skin injuries

Lacerations or abrasions without adequate explanation

Unexplained fractures in various stages of healing

Burns without satisfactory accidental explanation

Unexplained human bite marks

Subgaleal hematomas from severe hair pulling

Nonaccidental intra-abdominal trauma

|

|

|

|

Approximately 10% of all cases of child abuse involve burns.13 The most frequent cause of burns in abused children is scalding with hot water.13,14 The buttocks and perineum are frequently burned areas. Full-thickness, symmetric burns of the hands or feet suggest strongly that the extremities were held in a hot liquid (Fig. 5). Another commonly inflicted burn is from a cigarette. These lesions are often found on the palms, soles, or abdomen and often have an excavated center with raised edges.

|

THE BATTERED CHILD—OPHTHALMIC MANIFESTATIONS

The spectrum of ocular findings in the battered child is vast. Essentially any injury to the eye or adnexa could be due to abuse. An ocular injury may be as mild as periorbital edema or as severe as a ruptured globe. Signs of bilateral ocular trauma suggest inflicted injury because accidents usually involve only one eye. Perhaps one exception is bilateral periocular ecchymosis due to an accidental, single, central forehead trauma (Fig. 6). However, periorbital ecchymosis may also be caused by inflicted trauma with or without injury to the underlying globe. Attempts to date bruises by their color, particularly when the blood is accumulated in the loose skin of the lids, is notoriously unreliable.

|

There are some eye findings that almost always indicate trauma, and others that should raise the possibility of trauma (Table 3). Eyelid, conjunctival, corneal, and scleral lacerations are always due to trauma. Iridodialysis cannot be due to causes other than trauma, although this lesion can be mimicked by congenital anterior segment malformations such as Axenfeld-Reiger anomaly. Certain vitreoretinal injuries, such as commotio retinae and avulsion of the vitreous base are traumatic injuries. If a child with any of these injuries does not have an adequate explanation, the question of abuse should be raised. The ophthalmologist may conduct a complete physical examination to look for other indicators. Consultation with a multidisciplinary child abuse team is also indicated.

Table 3. Ocular Findings In Children That Raise Concern About Trauma

| Ocular Finding | Always Trauma? | Possibly Child Abuse? |

| Eyelids | ||

| Laceration | yes | yes |

| Bruising | no | yes |

| Conjunctiva | ||

| Hemorrhage | no | yes |

| Laceration | yes | yes |

| Cornea | ||

| Laceration | yes | yes |

| Scar | no | yes |

| Anterior Chamber | ||

| Hyphema | no | yes |

| Iritis | no | yes |

| Iridodialysis | yes | yes |

| Lens | ||

| Cataract | no | yes |

| Ectopia Lentis | no | yes |

| Retina | ||

| Detachment | no | yes |

| Hemorrhages | no | yes |

| Commotio | yes | yes |

| Vitreous | ||

| Vitreous base avulsion | yes | yes |

| Hemorrhage | no | yes |

| Optic Nerve | ||

| Atrophy | no | yes |

Modified from Levin AL: The Ocular Findings in Child Abuse. Focal Points Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists 26: 3–11, 1998.

Other eye findings such as hyphema and unilateral lens subluxation are usually due to trauma, but rarely have other causes. Subconjunctival hemorrhage is a common finding in child abuse, occurring in 4% to 10% of patients.9,10 Jain and colleagues15 reported a 1.7% incidence of subconjunctival hemorrhage in newborns as a result of the normal birth process. This is transient, and subconjunctival hemorrhage beyond the first 2 weeks of life should be considered suspicious.3 One must also rule out other causes of subconjunctival hemorrhage such as thrombocytopenia. Pertussis can result in severe 360-degree bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage. Consideration of appropriate diagnostic tests is always important in eliminating explanations other than abuse.

Other ocular signs such as cataract, iritis, retinal detachment, and optic atrophy occur frequently in the absence of trauma. In a child, however, the ophthalmologist must always consider the possibility of nonaccidental injury, especially if the finding is unilateral, history or other findings reveal inconsistencies and evidence to support a non traumatic diagnosis is absent. For example, Tseng and Keys16 discuss a case simulating congenital glaucoma in a 9-week-old physically abused infant presenting with hazy, enlarged corneas, elevated intraocular pressures, subluxated and cataractous lenses, vitreous hemorrhage, and hyphema.

Injuries, such as hyphema or ruptured globe, may be sustained in the course of discipline, occurring “accidentally” during a belt beating (Fig. 7). An unexpected move by the child or perpetrator not in control of the implement may cause injury to the eye. Spanking, as a form of discipline, may be controversial, but the use of an implement puts a child at significant risk for injury. Injuries to a child by beating should be reported to child protection agencies, even if the injury occurs “accidentally” in the course of the beating. Such circumstances clearly indicate that the perpetrator was “out of control” when the incident occurred. It is this loss of control that is one of the main features of the perpetrators.

MUNCHAUSEN SYNDROME BY PROXY

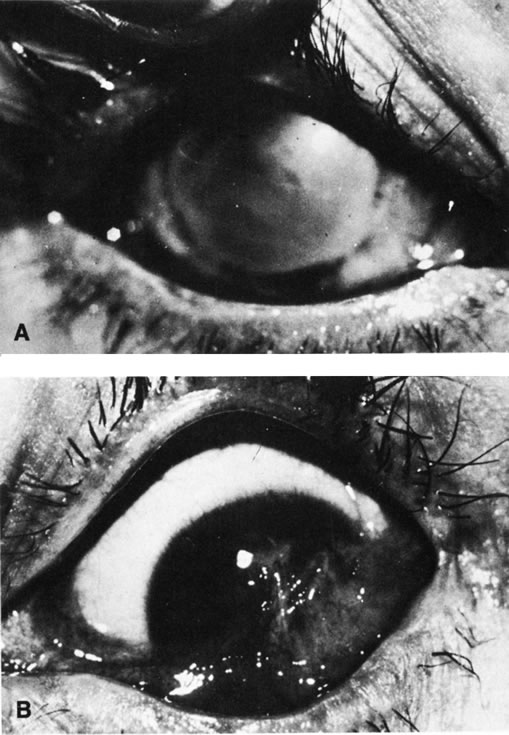

Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is a form of physical (and emotional) child abuse that occurs when a parent, the mother in over 90% of cases, causes the appearance of an illness by the falsification of history, creation of physical findings, or manipulation of laboratory test results. The most common presentation of MSBP is covert suffocation injury causing the child to have seizures or recurrent apnea. The presenting ocular sign may include subconjunctival hemorrhage that is sometimes associated with petechia of the face and perioral or perinasal injury. The perpetrator may induce vomiting in the child or feed the child substances that cause vomiting or diarrhea. Covert poisoning is also a common form of MSBP, and cases of injection of substances ranging from insulin to feces are well known. Reported ocular manifestations have been numerous and include recurrent conjunctivitis due to instillation of chemicals into the fornices. This has even resulted in corneal scarring with bilateral legal blindness (Fig. 8). Pupil and eye movement abnormalities due to toxic topical or systemic medications, recurrent periorbital cellulitis due to injection of foreign substances around the eye, and even intravenous injection of noxious substances into a child receiving chemotherapy for retinoblastoma have been reported. As a result of recurrent unexplained symptoms, the child may be subjected to multiple invasive diagnostic tests, procedures, and hospitalizations, and the physician ordering the tests becomes an unknowing participant in the battery of the patient. Physicians must be aware of the signs of MSBP that are summarized in Table 4 and may help to reveal the diagnosis.

Table 4. Signs Raising Possibility of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy

Disorder that is difficult to diagnose and

• Does not respond to treatment in predictable manner

• Does not fit into any known diagnostic category

• Intermittent and unpredictable symptoms

• Chronic

• “Never seen a case like this before”

Multiple caretakers or parents dissatisfied with care

Mother overly involved with child's care

• Speaks for the child

• Never leaves bedside

• Father absent or uninvolved

• Overly bonded maternal-child relationship

Mother very social and inappropriately happy during hospitalization

• Bonds with ward staff

• At ease with bad news

Mother with history of factitious illness

Siblings with unexplained illness

Mother with prior access to or experience in health-care system

Modified from Levin AL: The Ocular Findings in Child Abuse. Focal Points: Clinical

Modules for Ophthalmologists 26: 3–11, 1998.

SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME

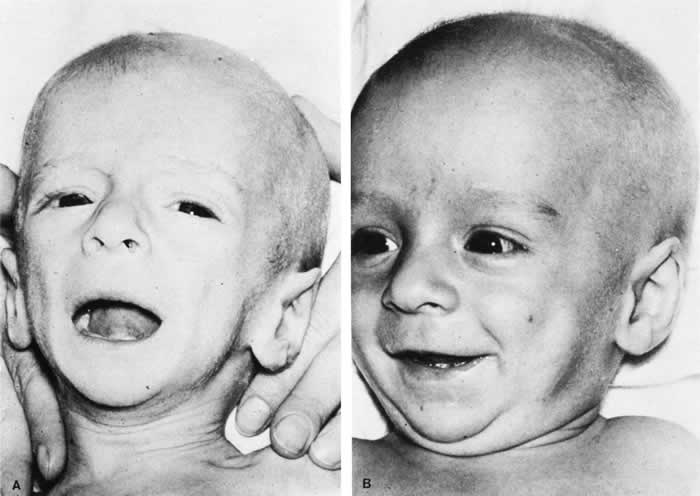

The triad of the SBS includes brain injury usually with hemorrhage, ocular injury, and skeletal injury. These children often have no external signs of trauma. The infant and young child are particularly vulnerable because of their relatively large head, weak cervical musculature, large size of the cranial vault in relation to the size of the brain,3 and immature, unmyelinated brain. Violent shaking causes repetitive anteroposterior and side-to-side disorganized head movement with abrupt acceleration-deceleration forces.7,17,18,19 The magnitude of acceleration-deceleration forces needed to cause brain and eye injuries in humans is extreme but not exactly quantified.20 Although in Caffey's original description, he inferred that normal play activities could cause SBS-like injuries, we now recognize that this is not the case.21

Abusive head trauma is the most common type of child abuse resulting in death,22 although it represents only 3% to 5% of all cases referred to child abuse teams.23 Assault represents more than half of all traumatic brain injury in the first year of life and 90% of brain injuries between 1and 4 years of life. The average age of SBS victim is between 5 and 10 months,22–31 with most children younger than 2 years of age.22,25,26,30 Victims up to 5 years old are rare. The mortality rate of SBS, based on studies with more than 10 patients, is approximately 8% to 61%,23 although this may be a reflection, in part, of separation or imprisonment of perpetrators after the first incident. Recidivism rates are high.

The most common perpetrators of SBS are biological fathers and biologically unrelated boyfriends of the mother.22,26,30,32,33 Babysitters, females 4.4 times more often than males,22 are the perpetrators in 4% to 20% of cases.22,26,33 Biological mothers commit this crime in 5% to 12% of cases.22,26,33 Only a minority (10% to 15%)23,33 of perpetrators confess, although it may be as high as 43%34 in fatal cases.

SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME: SYSTEMIC MANIFESTATIONS

Brain injury in SBS is common: Subdural hemorrhage is found in 10% to 93%, subarachnoid hemorrhage in 10% to 72%, posterior interhemispheric blood in 20% to 100%, stroke in 12% to 50%, intraparenchymal hemorrhage in 5% to 30% and parenchymal tears in 0 to 100%. 23,24,26,29,35 Increased intracranial pressure or cerebral edema is found in 44% to 85%.23,35 The wide variation in incidence figures reflects the nature of the study populations: findings at presentation, in survivors, or at autopsy. At autopsy, subdural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and cerebral edema are the most consistent findings.21,34,36,37 Although one study using a mechanical model and autopsy investigation suggested that blunt head impact is required to generate the forces necessary to cause the brain injury of SBS,38 a wealth of clinical and pathologic investigations indicate that shaking alone can cause significant injury and even death. Perhaps calculation of forces does not allow for a full understanding as cellular and biochemical responses to shearing stress along with other factors such as anemia and hypoxia may play an important role that cannot be modeled. Violent shaking causes shearing forces that tear the bridging veins running from the cortex to the dural venous sinuses, resulting in subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Shearing also causes diffuse axonal injury with secondary brain edema.39,40,41,42 The diagnosis of brain injury is usually confirmed with computed tomography (CT) scan. However, the CT scan may initially be normal or show edema without hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful to find hemorrhage not visualized on CT43 and to date the findings seen on CT.

The long-term prognosis for children with brain injury secondary to SBS is poor. In one study, only 28% of survivors had normal neurologic exams on discharge from the hospital; this figure decreased to 8% to 14% in long-term studies.22 Late findings seen on imaging studies include cerebral atrophy, hydrocephalus ex vacuo, chronic subdural effusion, and encephalomalacia. Patients may have quadriplegia, diplegia, hemiplegia, mental retardation, developmental delay; learning disability, seizures (7% to 65%), and psychiatric/behavioral issues(28% to 50%).23,24,26,30,44

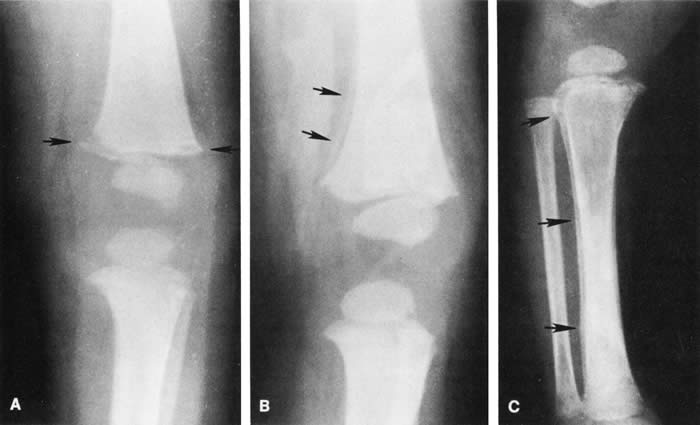

Skull fractures occur in 9% to 31% of shaken babies,23,30 with the parietal and occipital bones most affected. The characteristics of skull fractures that are highly suggestive of abuse include branching, stellate, crossing suture lines, multiple, greater than 5 mm wide, or progressively expanding fractures in a child less than 3 years of age.29 Rib fractures are the most common bone injury in SBS, and are usually posterolateral due to the perpetrator's hands grasping the child. Long bone fractures affect the tibia, forearm bones, femur, or humerus in decreasing order of prevalence. The characteristic metaphyseal fracture, which rarely occurs in young children except in the setting of abuse, results in a “corner” or “bucket handle” chip fracture at the end of the bone (Fig 9). Other injuries seen in SBS include hemorrhagic stripping of the periostium, spiral fractures, and nonsupracondylar humerus fractures—all due to shaking while the infant is held by an extremity, causing the long bones to be twisted and broken.29,30

SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME: OCULAR MANIFESTATATIONS

Retinal Hemorrhages

Retinal hemorrhage is the most common ocular manifestations of SBS. The incidence of retinal hemorrhages in SBS varies in published reports. This variation is in part due to methods of examination (ophthalmologists vs pediatricians, dilated vs undilated pupils) and the population studied. Overall, the incidence varies from 30% to 100%.18,21,30,38,51,52,53 The incidence in studies including children with abusive head trauma not due to shaking is lower than in studies only involving SBS. In postmortem studies, the incidence of retinal hemorrhages approaches 100%.34,51,54,55

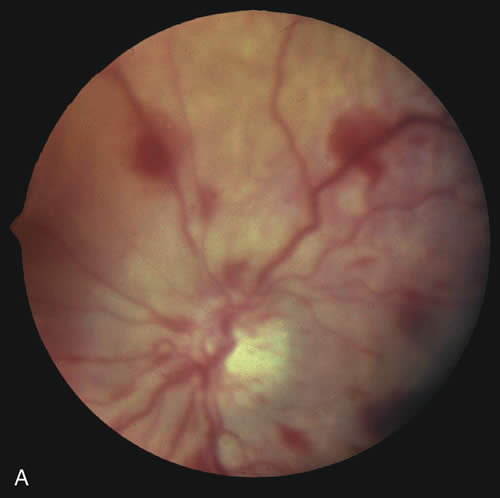

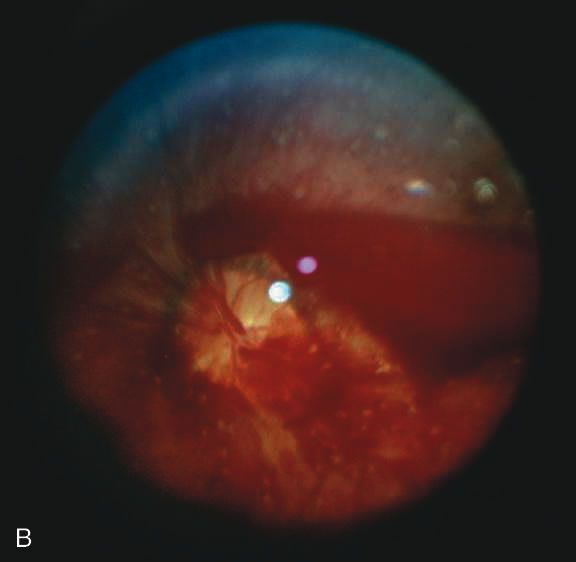

Findings range from a normal fundus to a small number of scattered intraretinal hemorrhages in the posterior pole to massive, confluent hemorrhages from the posterior pole to the ora serrata.(Fig. 10) The hemorrhages may be subretinal, deep intraretinal (dot/blot), nerve fiber layer (flame shaped) or preretinal.19,45 Intraretinal hemorrhages are more common than preretinal or subretinal hemorrhages.32,46 Preretinal hemorrhages must be distinguished from traumatic retinoschisis (see later), which has particular diagnostic significance. White-centered retinal hemorrhages, although classically associated with endocarditis, can occur in any condition that causes retinal hemorrhages, including SBS. Vitreous hemorrhage may be small to massive, and may occur secondary to escape of blood from intraretinal collections or from torn vessels.19 Although vitreous hemorrhage may occur at the time of injury, it may also be a delayed finding occurring 1 to 3 days or more after the initial trauma.47,48

Retinal hemorrhages may be associated with papilledema in SBS. However, papilledema is seen in less than 10% of shaken babies.35, 49 These small, flame-shaped hemorrhages on and radiating around the optic nerve are not necessarily caused by shaking and may be seen in papilledema from any cause. However, retinal hemorrhages associated with SBS may be seen on the optic disc in the absence of papilledema.50

Retinal hemorrhage is usually bilateral but may also be asymmetric or unilateral. Retinal hemorrhage can not be dated with any precision and, therefore, should not be used to help determine when the abusive event occurred.46,47,56,57,58,59 At best, generalizations may be made with wide intervals. For example, intraretinal hemorrhages do not last months, and blood in schisis cavities does not go away in days. Retinal scars or optic atrophy do not form in days.

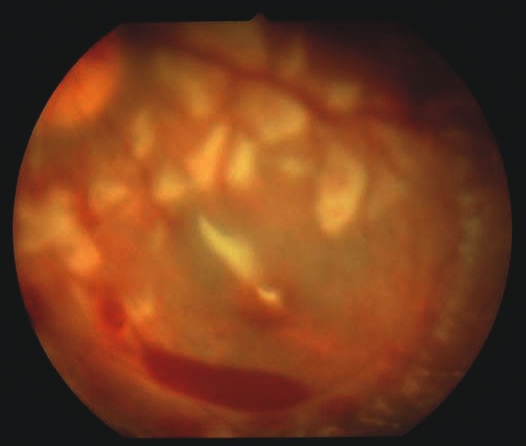

The pathophysiologic mechanisms of retinal hemorrhage in SBS are varied. Vitreous and perhaps orbital shaking is likely to be involved in most of the vitreoretinal injuries. In children, the vitreous is well attached to the retina at the macula, blood vessels, and the periphery. Shaking of an infant causes the vitreous to shake, which, in turn, applies shearing forces to the retina at points of firm attachment. These shearing forces at the macula may split the retina at any layer, causing the formation of a cystic cavity, which may be filled partially or completely with blood (Fig. 11). This traumatic retinoschisis has been well documented in abuse cases by ultrasound, electroretinogram, and pathology.34,58,60,61,62,63,64 Histopathology reveals a widening of the retinal layers or a stripping of the internal limiting membrane. The vitreous may stay adherent or detach. Clinically, to recognize this important finding in SBS, the examiner may observe a hemorrhagic or hypopigmented curvilinear edge to the schisis cavity, with or without a fold in the retina (Figure 11).50,65,66 Recognition of this edge helps distinguish retinoschisis from subhyaloid hemorrhage. However, subhyaloid hemorrhage, which may have originated from blood breaking out of a schisis cavity, may obscure the underlying schisis. It is important to follow any potentially shaken child with preretinal blood in the macula until that blood has cleared as the signs of schisis may be unmasked as the blood resorbs thus confirming the diagnosis of SBS. The retinal fold or hypopigmented line may be a complete circle or just an arc. In the long term, these patients may have surprisingly few sequelae and good vision as the cavity flattens spontaneously. There may also be findings of permanent curvilinear, hypopigmented scars or retinal folds. These provide clues to prior abuse.67

|

There does appear to be a statistically significant higher incidence of peripheral retinal hemorrhage in SBS versus accidental head trauma. Vitreous shaking and shearing forces may be responsible because the vitreous is well attached in the periphery at the vitreous base. This theory requires further investigation. Evidence from animal models suggests that there may also be a biochemical cascade of factors involved with vascular permeability and autoregulation that may also play a role in the generation of retinal hemorrhages in response to shearing stress.68 Other factors such as hypoxia and anemia may also contribute.

Shaking may also cause changes in the orbit that contribute to the generation of retinal hemorrhages. One of the authors (AVL) has performed orbital dissection on victims of SBS and accidental head trauma finding hemorrhage within the dura proper, orbital fat, cranial nerve sheaths, and extraocular muscle in the former but rarely in the latter. Other authors have described intrascleral hemorrhage at the junction of the optic nerve and globe.69,70 These findings suggest that there may be mechanical disruption to the circle of Zinn or other vessels running to the eye and trauma to the cranial nerves that carry autonomic supply involved with vascular autoregulation. In addition, orbital injury remains the only viable theory to explain the high incidence of optic nerve injury in survivors.

Other factors may also contribute to the appearance of retinal hemorrhages in SBS, although in a minor way. Terson's syndrome is the association of intracranial blood and retinal hemorrhages well recognized in adults in particular after spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage or ruptured aneurysm. Optic nerve sheath hemorrhage is also often associated with Terson's syndrome34,71,72 (Fig. 12). Some have theorized that the optic nerve sheath blood is due to tracking of blood from the subarachnoid or subdural space,29,73 whereas others attribute this finding to sudden elevation of intracranial pressure from intracranial bleeding.56,74,75 It remains unclear whether optic nerve sheath hemorrhages have a role in creating retinal hemorrhages. There is significant evidence to suggest that there is not continuity between the brain and optic nerve sheath through the subdural or subarachnoid space.76 In addition, Terson's syndrome may be observed in the absence of optic nerve sheath hemorrhage or with hemorrhage confined only to the anterior optic nerve sheath. Although optic nerve sheath hemorrhage is not uncommon in SBS, Terson's syndrome in children is rare.77 Further suggesting a lesser role for Terson's syndrome in the pathogenesis of SBS retinal hemorrhage is the absence of correlations between the side of the intracranial hemorrhages and the retinal hemorrhages or between elevated intracranial pressure and retinal hemorrhages in SBS.35

|

There remain still other theories for retinal hemorrhage in SBS that also seem to play a minor role. Some have suggested a Purtscher-like mechanism due to an increase in intrathoracic pressure when the perpetrator squeezes the child's chest. Although the characteristic white retinal patches of Purtscher retinopathy may be seen in SBS (Fig. 11), there appears to be no correlation with rib fractures,35 and the finding is very uncommon. The failure to see significant retinal hemorrhaging after the chest compressions of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in both animal models and humans also argues against a Purtscher-like mechanism.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of retinal hemorrhages in a child is vast. However, if one considers a child with the full spectrum of injuries seen in SBS, including brain, skeletal, and eye findings, most would not dispute that the retinal findings are due to nonaccidental injury. However, in a child with a small number of retinal hemorrhages and without retinoschisis, (Fig. 10A) the diagnosis of SBS may be less clear.

The birth process is likely the most common cause of retinal hemorrhages in newborns, varying in several reports from 11% to 31% or higher.4,15,78 These retinal hemorrhages are most common after vaginal or vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery.79–82 The exact mechanism is unknown, but there is no association with brain hemorrhages in these infants.79,81,83 Prostaglandin release may play an important role. The distribution of retinal hemorrhages secondary to the birth process may extend from the posterior pole to the ora serrata. Most often they are limited to dot, blot, or flame-type of hemorrhages but preretinal and less commonly subretinal hemorrhage may also be seen.79,81,84 Although macular hemorrhages are common,82,85 schisis has never been observed despite the examination of thousands of children. All types of retinal hemorrhages due to the birth process resolve by 6 weeks of age with the exception perhaps of deep foveal hemorrhage. The majority of hemorrhages clear much earlier. Most flame-shaped hemorrhages resolve by 3 to 5 days, with all resolved by 1 week.86,87 Any retinal hemorrhages seen beyond these dates should arouse suspicion of another cause. Retinal hemorrhages seen within the first 6 weeks of life may also be due to SBS, and additional investigations must be considered when appropriate.

Caretakers often relate histories of relatively minor head trauma as the cause of injuries that are otherwise generating the suspicion of SBS.21,34 After much study, most authors88–90 conclude that severe injury after a minor fall should raise the suspicion that the history is false and that the child has been abused. Furthermore, “most investigators agree that trivial forces such as those involving routine play, infant swings, or falls from a low height are insufficient to cause” the injuries seen in SBS.21,91 Even severe accidental head injury such as depressed skull fracture or intracranial hemorrhage does not routinely cause retinal hemorrhages.90,92,93 In compiling the available literature, retinal hemorrhage occurs in less than 3% of accidental head trauma, and then, almost always only in cases of severe, life-threatening injury.35,53,72,91,92,94,95 In the few cases of accidental head trauma with retinal hemorrhage, the bleeding is confined to the posterior pole with dot-blot, flame-shaped, or preretinal hemorrhages. Occasionally, these hemorrhages can extend to the midperiphery. But even the most severe accidental head trauma injuries do not cause the extensive retinal hemorrhages seen in SBS, except perhaps when the injury mechanism involves multiple acceleration-deceleration events such a motor vehicle accident in which the car strikes several objects or rolls consecutively resulting in death of the child. Retinochisis has not been observed after accidental head trauma, although there is one case of a child who may have suffered a severe crush injury to the head (five skull fractures with brain extrusion) and also a few adults with other causes of injury who have been observed to have paramacular folds or subinternal limiting membrane hemorrhage. These cases should not be taken to imply that in the SBS age range, macular schisis has a differential diagnosis other than SBS.

There are a variety of other causes of retinal hemorrhage in children (Table 5). However, these are usually easily identified on the basis of history, systemic physical examination, or ocular examination. The retinal hemorrhages are almost always few in number and confined to the posterior pole unless there is predisposing retinal pathology which causes the hemorrhages to be located elsewhere (e.g. at the active ridge in retinopathy of prematurity). If an examining ophthalmologist finds retinal hemorrhage in a patient with these systemic problems, the physician must also attempt to understand if the disease could be the cause of the hemorrhages or if the child has been abused.

Table 5. Retinal Hemorrhages in Childhood*

| Etiology in Children <5 years of age | Identifying Features† |

| Accidental head trauma | Obvious history of trauma |

| Hyperviscosity/polycythemia anemia | Abnormal CBC Hg, <5, usually with thrombocytopenia, vascular tortuosity and dilation |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with chest compressions | History of CPR, very few peripapillary intra or preretinal hemorrhages |

| ECMO | History of ECMO |

| Hypoxia/asphyxia | Vascular tortuosity/dilation |

| Incontinentia pigmentia | Skin and dental abnormalities, peripheral avascular retina, hemorrhage peripherally only, temporal retinal traction |

| Malaria | Abnormal blood smear |

| Menke's Disease | Abnormal hair |

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | Environmental exposure, clinical symptoms improve in new setting, increased carboxyhemoglobin |

| Meningitis | Abnormal lumbar puncture |

| Coagulopathy | Abnormal PT/PTT/INR/bleeding time |

| Collagen disorders | History of head trauma, clinical systemic findings |

| Endocarditis | White-centered hemorrhages, heart murmur or history of predisposing cardiac disease, abnormal echocardiogram, positive blood cultures, fever |

| Leukemia | Abnormal CBC |

| Prematurity | Peripheral avascular retina with neovascularization |

| Cyanotic congenital heart disease | Heart malformation, low oxygen saturation, dilated and tortuous retinal veins |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Characteristic rash, history of exposure/tick bite |

| Sepsis | Fever, positive blood culture, hypotension |

| Galactosemia jaundice | Hepatosplenomegaly, formula/breast milk intolerance, |

| Glutaric aciduria | Chronic macrocephaly, extrapyramidal signs on recovery, basal ganglia involvement on CT |

| Valsalva | Usually exclusively preretinal hemorrhage |

| Increased intracranial pressure intracranial pressure | Papilledema, other evidence of increased |

| Vasculitis | Perivascular hemorrhage |

| Vitamin K Deficiency | Prolonged PTT/abnormal INR, history of missed neonatal dose/malabsorption/liver disease |

* Unless otherwise noted, retinal findings confined to a small number of intraretinal or preretinal hemorrhages in the posterior pole.

† Identifying features not meant to be complete CBC, complete blood count; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CT, Computed tomography; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; INR, International Normalized Ratio; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

OTHER OCULAR INJURIES

Victims of SBS may sustain other ocular injuries either due to the acceleration-deceleration events or from concomitant blunt eye trauma. Partial or total retinal detachment may occur, likely secondary to the same types of shearing forces described earlier. Most of the reported retinal detachments have been rhegmatogenous.96–98 Macular edema may be detected, although it is uncommon.99 Although edema may suggest retinal ischemia, this should be differentiated clinically from commotio, which indicates blunt trauma to the globe. Subconjunctival hemorrhage is another rare finding in SBS,100 as is hyphema. Subconjunctival hemorrhage may be due to associated strangulation. Cranial nerve palsies may occur affecting nerves III, IV, V, VI, and VII.

OUTCOMES

Subretinal fibrosis is a late finding and represents scar tissue formation.99 Other late findings include optic atrophy,9 the circumlinear paramacular hypopigmented scars or folds due to schisis, and peripheral chorioretinal scarring. Injury to the occipital cortex is the most common cause of permanent visual loss in these patients. There are many mechanisms including infarction, contusion, shearing/laceration, diffuse axonal injury, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, and contre-coup injury.101–104

The majority of retinal hemorrhages caused by shaking with or without blunt head trauma clear without sequelae. Retinoschisis also usually has a good visual prognosis. However, preretinal hemorrhage over the fovea and vitreous hemorrhages may cause amblyopia. Although surgical evacuation is usually unnecessary, close follow-up and patching may be indicated. The incidence of blindness in long-term survivors of SBS is 15% to 28%. 24,44 An additional 15% experience other forms of visual impairment. Even children without permanent retinal damage may have visual loss secondary to brain injury. One study showed that 35% of children without retinal injury had permanent visual loss.105 Other forms of permanent visual impairment due to SBS include visual field loss, color vision impairment, decreased contrast sensitivity, and abnormal binocularity. Considering all forms of visual impairment, 67% of patients in one study of SBS were affected.30