Table 1. Advantages of Surgical Approaches to the Rectus Muscles

| Fornix (Cul-de-sac) Incision | Limbal Incision |

| Less trauma | More complete visualization of the tendon of the muscle |

| Less foreign body sensation | Easier to understand |

| Dellen uncommon | Incision will release conjunctival and Tenon's tissue forces |

| Preserves conjunctival vasculature at the limbus | Suitable for en bloc recession technique |

| Suture closure of incision is not required | Easier to perform adjustable suture |

| Incision protected by eyelid | |

| Better cosmesis | |

| Conjunctiva at limbus is preserved if a further glaucoma (filter) procedure is needed | |

| One incision can be used to approach two adjacent muscles |

Table 2. Disadvantages of Common Surgical Approaches to the Rectus Muscles

| Fornix (Cul-de-sac) Incision | Limbal Incision |

| Difficult to comprehend | Disrupts limbal vasculature |

| Does not release subconjunctival tissue bands or restriction | Requires sutures to close |

| Limited visualization | Foreign body sensation |

| Limited access to muscle | Dellen formation |

| Requires more assistant participation | |

| More difficult to perform suture adjustment |

The type of anesthetic is chosen after consultation between the parent or patient and the surgeon. During this discussion, the advantages and disadvantages of each form of anesthesia should be explained and the most suitable form selected. The surgeon should assist the parent or patient in choosing the anesthetic. The use of a general anesthesia is most suited for the young or anxious patient. If the surgeon anticipates difficulty with the procedure, such as a re-operation, or if a “lost” muscle is going to be “found,” general anesthesia is the preferred technique. If both eyes require surgery, it is undesirable to administer a retrobulbar anesthetic that temporarily may decrease the patient's visual acuity. In these situations, topical, perimuscular, or general anesthesia is preferred.

If the result of forced duction testing is critical in determining the amount of surgery to be performed, a local or topical anesthetic may be considered. During general anesthesia, the use of a depolarizing agent, such as succinylcholine, can alter the tone of the extraocular muscles temporarily. This alteration may affect the result of forced duction testing.36 The increased tone of the extraocular muscles can be avoided with the use of a nondepolarizing agent, such as pancuronium. If postoperative suture adjustment is required, it may be several hours before the patient recovers sufficiently from general anesthesia to permit the adjustment to be performed.

Local anesthesia has been used for strabismus surgery for two centuries. Recent advances have made local anesthesia the preferred anesthetic in mature, cooperative patients.23 Because of the myotoxicity of bupivacaine, this agent should be avoided if a retrobulbar block will be used.37 Intravenous sedation with fentanyl citrate combined with midazolam will prepare cooperative adolescents for the administration of either retrobulbar anesthetic (1.0 to 2 ml of a 2% mepivacaine (Carbocaine) solution or a perimuscular block injected subconjunctivally over the muscle insertion. Topical anesthetic, either 4% lidocaine hydrochloride or a 1% to 4% solution of cocaine supplemented with intravenous sedation also may be used. The latter methods provide the patient with anesthesia of the globe without akinesia and permit the patient to participate in suture adjustment in the operating room if needed.

Table 3 lists instruments that are used frequently for strabismus surgery.

Table 3. Surgical Instruments Commonly Used for Strabismus Surgery

| Instrument | Catalogue No. | Quantity |

| Castroviejo caliper | E2404* | 1 |

| Lester fixation forceps | E1656* | 1 |

| Jameson muscle forceps (right) | E2331* | 1 |

| Castroviejo suturing forceps (0.5-mm teeth) | E1798* | 1 |

| Manhattan eye and ear suturing forceps | E1831* | 1 |

| Jameson muscle hook | E0586* | 2 |

| Stevens curved tenotomy hook | E0600* | 2 |

| Castroviejo needle holder (straight with lock) | E3861* | 2 |

| Desmarres lid retractor size 01 | E0981* | 1 |

| Desmarres lid retractor size 0 | E0980* | 1 |

| Westcott curved blunt-tip tenotomy scissors (right) | E3320* | 1 |

| Barraquer wire eyelid speculum (adult, pediatric) | E4106* | 1 each |

| Large resection clamp | Weck 4825† | 1 |

| Weck eye rakes | Weck 481180† | 2 |

| Heavy straight Mayo scissors | Weck† | 1 |

| Small resection clamp | SP7/21185* | 1 |

| Malleable retractor | Sparta 330–520‡ | 1 |

* Storz Instrument, St. Louis, MO

† Linvatec, Largo, FL

‡ Sparta Surgical, Hayward, CA

PREPARATION

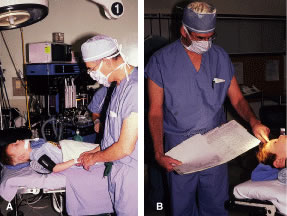

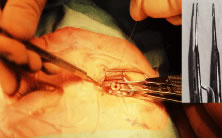

Instrument selection is reviewed by the surgeon (Fig. 1). The patient is positioned so that the head is stabilized, and a shoulder bolster or “roll” is placed under the patient's shoulders to extend the neck slightly (Fig. 2A). The patient is identified, as is the eye to receive surgery (see Fig. 2B).

|

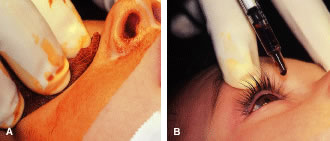

The eyelids and surrounding skin are prepared with two scrubs using a 10% povidone iodine (Betadine) solution that is diluted 50:50 with warm saline38–41 (Fig. 3A and B). The conjunctival cul-de-sacs are irrigated with a bulb syringe and warm saline. Silver protein precipitating solutions, such as Argyrol are not used. A drop of 1% phenylephrine hydrochloride may be instilled into the conjunctival cul-de-sacs to reduce conjunctival bleeding (Fig. 4). The surgical field is isolated with a sterile adhesive barrier drape (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). The instrument tray is positioned, and sterile cotton-tipped applicators are placed on either side of the head so that they are available for sponging the field (Fig. 6). A wet-field or bipolar cautery is available. The surgeon is seated at the head of the operating table. The assistant sits to the left of the surgeon, and the surgical technician sits to the right (Fig. 7). Consistency in the procedures that are used to prepare a patient for surgery, such as positioning of the patient and location of the surgeon and the assistants, helps to eliminate confusion among the operating room staff before each procedure. Surgical instruments can be placed on a Mayo stand if a surgical technician is not available to pass instruments to the surgeon (see Fig. 6). The clinical record is positioned where the surgeon can refer to it.

|

|

|

|

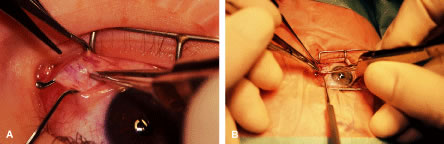

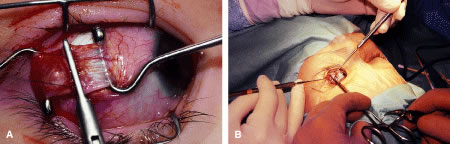

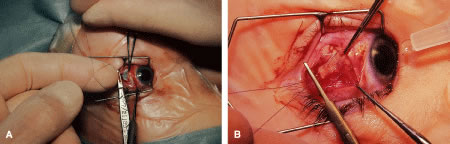

RECESSION PROCEDURE: FORNIX INCISION

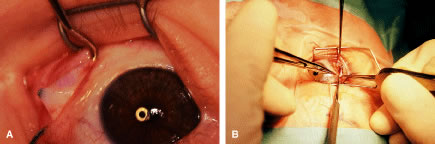

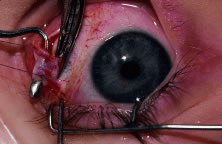

This procedure is recession of the right medial rectus muscle. The eyelids are separated with a Barraquer open-blade wire eyelid speculum (Fig. 8). The open-blade design provides more room for exposure and makes it easier to pass the suture needles, especially in small children or when large recessions are performed. The globe is grasped with a Lester forceps at the limbus. It is best to grasp the limbus with the forceps held perpendicular to the globe and then to position the forceps so that they are rotated and lie tangential to the globe. Forced ductions are performed to detect any restriction of movement of the globe (Fig. 9).

|

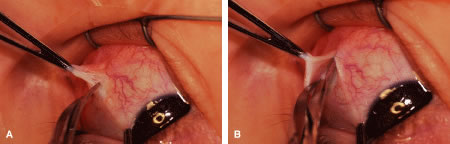

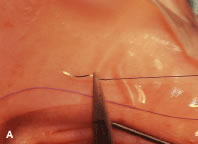

The globe then is gently elevated from the orbit or proptosed at the same time it is abducted or adducted to prepare for the incision. Elevation of the globe helps to separate the horizontal rectus muscle from the inferior rectus muscle so that the inferior rectus muscle is not cut when the incisions are made. The conjunctiva is grasped by the assistant with a Manhattan toothed forceps (Fig. 10). This forceps has teeth that are angled outward and are designed to grasp conjunctiva, as well as the deeper subconjunctival tissue, so that when the blunt-tipped Westcott scissors cuts into the tented tissue, an incision is made into the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule (Fig. 11A and B). If the incision does not completely penetrate Tenon's capsule and the intermuscular septum to the scleral surface of the eye, additional tissue (anterior Tenon's tissue and/or intermuscular septum) is grasped with the Manhattan forceps and at least one additional cut is made.

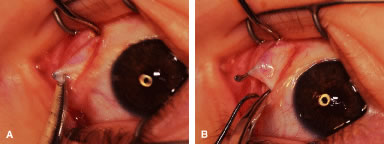

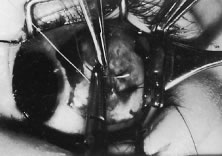

A Stevens' tenotomy hook is passed by the surgeon into the incision and is rotated so that it can be slid underneath the muscle insertion with the tip of the hook held tangential to the globe (Fig. 12). The hook should be passed 2 to 3 mm posterior to the expected location of the muscle insertion. Care is taken not to incorporate intramuscular septum or other adventitial tissue on the hook. When the lateral rectus muscle is secured with the Stevens' or Jameson muscle hook, care should be taken not to bring the inferior oblique muscle up to the insertion (Fig. 13). When the muscle is secured with the Stevens' hook, the hook and the inferior edge of the muscle insertion are elevated and a Jameson muscle hook is passed between the tented muscle tissue and the sclera to secure the muscle at its insertion (Fig. 14). Care is taken to include the entire insertion of the tendon on the hook. The tip of the Jameson hook is gently elevated by depressing the heel of the hook. This maneuver helps to ensure that the entire tendon of the muscle remains captured on the hook. A Stevens' tenotomy hook is placed in the incision, this time anterior to the insertion beneath the conjunctiva (Fig. 15). The Stevens' hook is passed posterior over the orbital surface of the muscle (Fig. 16). Gentle pressure on the Stevens' hook is directed posterior so that the check ligaments and Tenon's tissue that overlie the muscle belly are separated from the muscle capsule with blunt dissection. The hook usually is passed posterior for about 10 mm. When recessing a lateral rectus, attachments between the underside of the lateral rectus and inferior oblique are broken (Fig. 17). Two or three passes over the muscle are made, and, with simultaneous countertraction on the Stevens' hook and the Jameson hook, the conjunctiva is elevated and pulled over the tip of the Jameson hook (Fig. 18A and B).

|

The intermuscular septum and Tenon's capsule at the ball-like tip of the Jameson hook are incised with a Westcott scissors (Fig. 19). A Manhattan forceps can be used to elevate the intramuscular and Tenon's tissue to facilitate this step. Care is taken to incorporate the entire muscle tendon on the Jameson hook before this cut is made. If it is evident that there is residual tendon that is not placed on the hook, the additional tendon, intramuscular septum, and anterior Tenon's tissue are reflected over the tip of the Jameson hook with the closed tips of the Westcott scissors or a small muscle hook.

A Stevens' hook is inserted in the opening in the intermuscular septum created by the scissors and is passed anterior to the insertion. Parks has referred to this maneuver as the “pole test.” This maneuver is done to verify that the tendon of the muscle has not been split and that the complete muscle tendon is incorporated on the hook. Leaving residual slips of muscle tendon will partially or completely negate the effect of a recession procedure (Fig. 20A and B).

The anterior Tenon's capsule is cut free from the muscle insertion by grasping the loose tissue anterior to the insertion of the tendon with a forceps and gently tenting it (Fig. 21A and B). Care is taken not to grasp muscle capsule or muscle tendon fibers in the forceps. To best accomplish this step, the blunt tipped Westcott scissors is placed perpendicular to the globe. Cleaning the tissue anterior to the muscle permits passing the needle accurately through the rectus muscle tendon with unobstructed visualization. If the capsule of the muscle tendon is cut, the tendon may split. Two small Stevens' hooks are used to elevate the conjunctiva and expose the intermuscular septa and the tissue overlying the muscle capsule. These tissue bands are cut with the Westcott scissors (Fig. 22A and B). Care is taken not to cut into the muscle or the capsule of the muscle (Fig. 23). The intermuscular septa can be cut 3 to 4 mm back for recessions and 5 to 9 mm back for resections.42

The tendon of the rectus muscle is elevated by lifting it away from the globe with the Jameson hook in a plane that is perpendicular to the surface of the globe. With gentle traction on the muscle insertion with the Jameson hook, a fine spatulated needle with a synthetic absorbable suture is woven through the tendon 1 mm from its insertion to the globe (Fig. 24). The needle exits at the superior edge of the muscle tendon and is then passed back underneath the tendon of the muscle (Fig. 25A and B). The needle is then passed back through the tendon from underneath (lock bite) and out the anterior surface of the tendon, taking a 2-mm portion of tendon that will be incorporated into the double-lock knot. Taking too large a lock bite will tend to narrow the width of the muscle tendon (Fig. 26A and B). The two sutures are brought up and held by the surgeon's thumb on the frets of the Jameson hook (Fig. 27). A blunt-tipped Westcott scissors is used to cut the muscle tendon free from its insertion. The cutting blade of the Westcott scissors is passed posterior to the muscle insertion. Care is taken not to push the tip of the scissor into the insertion but rather to pass the posterior tip of the scissor behind the muscle tendon, in the free space created by elevating the muscle with the Jameson hook. Two or three snips usually are required to remove the muscle from the globe. Care is taken to cut the scleral portion of the insertion flush with the globe. Leaving a large stump at the old insertion will leave a vertical white band of tissue that will show through the conjunctiva and leave an unsightly scar.

|

|

The muscle is suspended to verify that both the muscle tendon and the muscle capsule are incorporated with the suture and its lock bites (Fig. 28). In addition, pulling the sutures superior and inferior will assure the surgeon that the transverse suture that was woven through the tendon was not cut when the muscle was removed from the globe (Fig. 29).

The globe is stabilized with two locking Castroviejo forceps with 0.5-mm teeth (Fig. 30). Care is taken to grasp the most superior and most inferior portions (for vertical muscle, the most lateral and most nasal portions) of the insertion. For recessions, exposure of the sclera posterior to the insertion is obtained by abducting or adducting the globe while applying a gentle lifting action of the forceps at the insertion. This elevating, or proptosing the globe from the orbit, opens the edges of the conjunctival-Tenon's incision and provides improved exposure of the sclera where the muscle will be reattached.

|

A Castroviejo caliper is used to mark a point on the sclera at a predetermined distance from the posterior portion of the muscle insertion (Fig. 31). Some surgeons prefer to mark the sclera the using the limbus as a reference point. These surgeons believe that it is more accurate to measure from the limbus than from the insertion of the rectus muscle because the insertion may have some anatomic variation. If a large recession procedure will be performed, measurement from the limbus will introduce a cord effect that will increase the amount of recession achieved (Fig. 32). To reduce this effect, William Scott has designed a curved ruler that provides a more accurate measurement of the arc. It is important for the surgeon to be careful and consistent with the measurement technique so that the effect of the surgical procedures can be critically evaluated.

The needle is grasped with a locking Barraquer needle holder at the middle portion of the shaft. Grasping the S wedged portion of the needle can cause the needle to roll within the jaws of the needle holder and this can increase the risk of penetration of the sclera. At the mark created by the caliper, there is usually a small dimple or depression in the sclera. The mark results from expressing water from the sclera so that the blue color of the uvea is seen. Because the muscle will attach to the globe at the point at which the needle tip enters the sclera, care is taken to start the intrascleral needle pass at the point marked by the caliper (Fig. 33). Care should be taken not to introduce any unintentional supraplacement or infraplacement effect of the tendon at the new insertion. The width of the insertion should be preserved: The width of the new insertion should equal the width of the original insertion. If the width of the insertion is not preserved, the muscle will not pull up to the new insertion evenly (Fig. 34A and B). If there is a sag in the new insertion caused by the new insertion site being too narrow, the suture can be passed back through the insertion to pull the center of the sagging muscle tendon back to the insertion (Fig. 35). The fine wire needles need to be passed following the curvature of the needle tip. Attempts to elevate the tip of the needle while it is in the sclera can cause the needle shaft to bend (Fig. 36A and B).

Some surgeons advocate a “crossed-swords technique” so that the second needle pass does not cut the suture from the first needle pass. With appropriate magnification, the other end of the suture is easily avoided. Once the needles have been passed through the sclera, the muscle is pulled up to its new insertion (Fig. 37). A Stevens' hook is used to keep the Tenon's and other surrounding tissue from being drawn into the insertion. The synthetic absorbable sutures tend to drag Tenon's tissue when the suture comes in contact with this tissue. Coating the suture tends to minimize this problem but does not completely eliminate it. The muscle is tied with a surgeon's (double throw) knot that is further secured with two or three square knots. The new insertion is checked and measured to verify that the muscle is in the desired position. After the measurement is checked, the locking Castroviejo forceps are removed.

The conjunctival edges of the wound are repositioned or swept closed with a muscle hook. The wound is not sutured. After the procedure, we do not use ointments or occlusive dressings. A drop of an antibiotic-steroid solution can be applied at the discretion of the surgeon.

RESECTION PROCEDURE: FORNIX INCISION

This procedure is a resection of a lateral rectus muscle. The approach to the rectus muscle to be resected is similar to that of the recession. The limbus is grasped with a Lester forceps. The globe is rotated up and away from the muscle to be resected. The conjunctiva is incised, and the rectus muscle is grasped with a Stevens' hook that is replaced with a Jameson hook. The Tenon's tissue and intermuscular septa are cut and reflected onto the Jameson hook. The intermuscular septa are cut with a Westcott scissors. The rectus muscle tendon is then suspended between the Jameson muscle hook (Fig. 38).

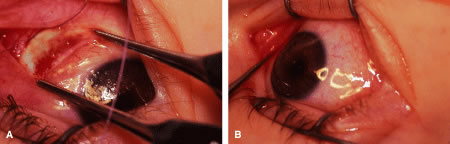

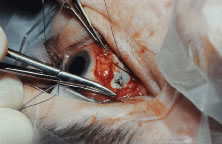

|

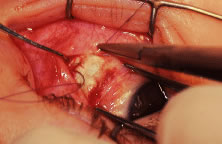

A fine-wire spatula-tip needle is woven through the muscle or tendon. Care is taken to avoid the anterior ciliary vessels on the orbital surface of the muscle (Fig. 39). The resection effect is achieved by measuring the location of the transverse suture from the posterior portion of the Jameson hook at the insertion to a predetermined point on the muscle tendon. Various locations can be used as reference points. This measurement can be taken from the anterior, middle, or posterior portion of the Jameson hook under the muscle. Periodic review of the effects of the operation will determine the amount of surgical correction that is achieved for each surgeon's individual technique. The suture is passed back through the tendon on the origin of the muscle side of the transverse suture. The suture is secured to the tendon with double-throw lock knots (Fig. 40). The muscle is clamped with a fine-tipped vascular clamp (Fig. 41A). A vascular clamp is used because it minimizes the crush damage to tissue that is held in the clamp. Care is taken not to include the transverse suture or any of the lock knots in the clamp. The clamp is stabilized on the drape with a towel clip (see Fig. 41B). A Stevens' hook is used to pull the conjunctiva and anterior Tenon's tissue away from the muscle, and a Westcott scissors is used to cut the muscle free from its insertion (Fig. 42). The muscle stump that is to be resected is grasped with forceps and elevated from the clamp. The resected tendon is then cut free from the clamp with a Westcott scissors (Fig. 43). The sutures are pulled away from the jaws of the clamp by the assistant so that they are not cut. A wet-field cautery is used to cauterize the stump of muscle that is held in the clamp (Fig. 44). The muscle insertion is grasped with a locking Castroviejo forceps in the center of the insertion. Each needle is passed from the upper or lower (for a vertical rectus, medial or lateral) pole of the insertion to exit near the center of the old insertion. The intrascleral bite is made in sclera that is just anterior to the insertion. This location is used to allow the needle to pass through the thickest portion of the sclera (Fig. 45). At the midpoint of the insertion, the tip of the needle is brought out of the sclera and the needle is regrasped and passed through the central portion of the muscle tendon on the origin side of the previously placed transverse suture (Fig. 46). A double-throw knot is tied, and the knot is pinched by the surgeon's index finger and thumb (Fig. 47A and B). The muscle clamp is removed, and the knot is pulled down to the muscle by elevating the suture and snugging it down in a stepwise fashion. Two or three additional square knots are added to secure the muscle to the new insertion (Fig. 48). The muscle is inspected to verify that Tenon's tissue is not drawn into the insertion. The knot is trimmed, and conjunctiva is reposited over the muscle with a Stevens' hook (Fig. 49).

|

|

|

|

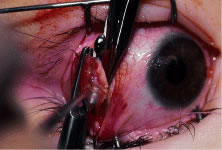

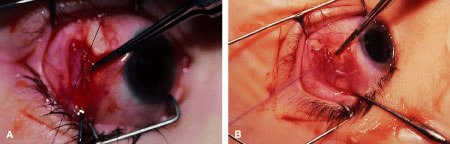

RECESSION PROCEDURE: LIMBAL APPROACH

The surgeon and the assistant sit opposing each other on either side of the patient's head. The surgical technician is located between the surgeon and the assistant.

Two 6-0 silk stay sutures are passed through the conjunctiva and superficial scleral tissue at the limbus (see Fig. 49). These sutures are used to stabilize the globe during the procedure. These stabilizing sutures attached to bulldog clamps will hold the globe in adduction or abduction as required.

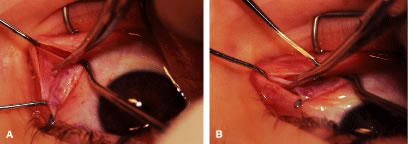

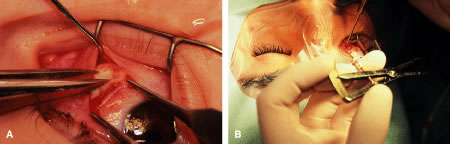

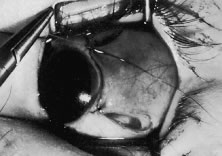

A no. 15 surgical knife or other similar instrument is used to penetrate the conjunctiva at the limbus (Fig. 50). Care is taken to approach the limbustangential to the globe so that inadvertent penetration of the sclera or cornea is avoided. A Westcott scissors also may be used to incise the conjunctiva at the limbus. To facilitate this step, conjunctiva is lifted gently with a 0.5-mm Castroviejo forceps (see Fig. 50).

|

A blunt-tipped Westcott scissors is used to extend the incision for about 3 clock hours (Fig. 51). Once the fused area of conjunctiva and anterior Tenon's capsule has been penetrated, blunt dissection is performed to carry the limbal incision back toward the muscle. This maneuver is best accomplished by directing the closed tips of a blunt-tipped Westcott scissors into the tissue and letting them open to spread the tissue in a plane between the scleral surface and the underside of Tenon's tissue. The limbal incision is extended radially with a Westcott scissors (Fig. 52). Care is taken to avoid cutting into the anterior portion of the rectus muscle insertion (Fig. 53).

|

|

Figure 54 shows the conjunctiva being elevated by the assistant with Castroviejo forceps. The anterior extension of the muscle can be seen.

|

A Jameson hook is passed under the rectus muscle about 2 mm posterior to the insertion (Fig. 55). The insertion has been identified previously with a Stevens' hook that is used to lift up the tendon to facilitate passage of the Jameson hook.

Figure 56 shows sharp dissection of the intermuscular septa and the check ligaments that extend from the orbital surface of the muscle. The assistant applies gentle traction to the conjunctiva to show the surgeon the weblike bands that are to be cut. Care is taken not to penetrate the muscle capsule because penetration can injure the muscle and will cause bleeding. This dissection is carried back about 4 to 5 mm for recessions and 5 to 9 mm for resections.

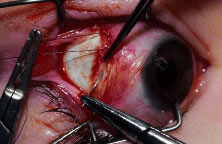

A single-armed 6-0 synthetic absorbable suture is passed through the muscle tendon near its insertion (Fig. 57). A double-lock bite is taken with the needle, and the suture is tied with two square knots to secure it to the upper and lower poles of the tendon of the rectus muscle. The muscle is lifted or tented off of the surface of the globe with a Jameson hook. A Westcott scissors is used to cut the muscle free (Fig. 58).

|

|

The assistant holds the Castroviejo caliper that marks the location of the new insertion (Fig. 59). Care is taken to locate it directly posterior to the stump of the old insertion and to avoid inadvertent supraplacement or infraplacement of the new insertion.

|

An intrascleral passage of the needle is used to secure the muscle to the globe (Fig. 60). The intrascleral bites are usually 3 to 4 mm in length. The superior and inferior pole sutures are tied to secure the muscle to its new insertion site (Fig. 61), and the wound is inspected. The new insertion is measured to ensure that the appropriate amount of recession effect has been achieved. The sutures are trimmed, and the conjunctiva is brought back to the limbus (Fig. 62). Care is taken to identify the conjunctival tissue. Confusion may occur when an attempt is made to differentiate this tissue from Tenon's tissue. A fine absorbable suture such as 8-0 collagen is used to secure the conjunctiva at the limbus (Fig. 63). If an en bloc recession technique is used, or a bare sclera closure is required, the conjunctiva is recessed 4 to 5 mm back from the limbus, leaving the sclera between the anterior conjunctiva edge and the limbus uncovered. This technique is useful when conjunctival and subconjunctival tissue is contracted or when it restricts movement of the globe.

|

|

|

|

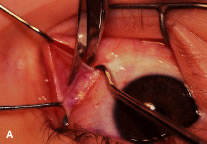

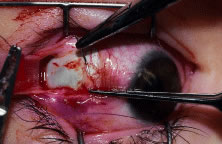

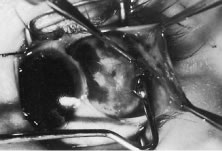

RESECTION PROCEDURE: LIMBAL APPROACH

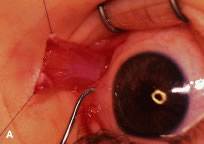

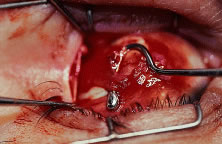

Incision is made into the conjunctiva at the limbus (Fig. 64).

|

The assistant elevates the conjunctiva while the surgeon uses a Stevens' hook to elevate the rectus muscle (Fig. 65). A Jameson muscle hook is passed under the muscle tendon in a plane that is tangential to the scleral surface, about 3 mm behind the tented rectus muscle insertion. Figure 66 shows the rectus muscle on the Jameson hook.

|

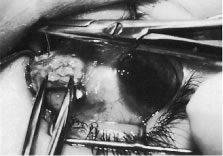

The surgeon cuts the intermuscular septa free from the muscle capsule (Fig. 67). A Castroviejo caliper is used to measure the amount of tendon that will be resected (Fig. 68). A Jameson resection clamp is placed on the muscle at the point of anticipated resection. Measurement is made from the portion of tendon that is on the posterior edge of the Jameson hook to the resection clamp. Exposure is facilitated with a Desmarres retractor.

|

|

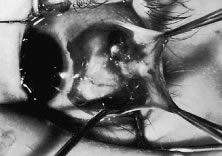

The muscle is cut free from its insertion (Fig. 69). The surgeon holds the Jameson clamp to elevate the muscle from the globe, and, using the other hand, the surgeon cuts the muscle free from the globe. The muscle stump is cut so that it is flush with the globe.

|

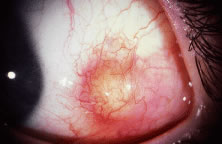

The globe is stabilized with a 0.5-mm-toothed Castroviejo forceps (Figs. 70 and 71). A mattress stitch with a double-armed 6-0 synthetic absorbable suture is placed through the most inferior portion of the insertion. The second needle is passed 1 mm below the central portion of the insertion. The initial penetration of the needle is just anterior to the insertion, and a secure bite is taken of the former insertion so that the needle exits just posterior to the old insertion. The needle is then passed underneath the Jameson resection clamp through muscle tendon, and the two sutures are held with a bulldog clamp to keep them separate from the sutures that are later passed through the upper pole of the insertion. Figure 71 shows the sutures being tied. This maneuver will effectively bring the resected muscle tendon up so that it can be reinserted at the insertion. Once the muscle is tied securely, the Jameson resection clamp is released and then advanced to the cut end of the insertion (Fig. 72). Under direct visualization, a Westcott scissors is used to trim the excess muscle stump. Care is taken to leave at least 1 mm of muscle tendon in front of the two sutures that secure the muscle to the insertion. After the muscle stump has been inspected, the conjunctiva is advanced back to the limbus (Fig. 73). Two 8-0 collagen sutures are used to secure the conjunctiva at the limbus. The small open radial portion of the incision will heal without suture closure. If the surgeon “buries the knots” under the conjunctiva near the limbus, the patient will have less foreign body sensation. Figure 74 shows the eye immediately after a recess-resect procedure. The conjunctiva should be smooth at the limbus to prevent disruption of the tear layer and formation of dellen. The eye is not patched. Antibiotic drops or antibiotic-steroid drops may be used at the discretion of the surgeon.

|

|

|

|