1. WHO Global AIDS Statistics: AIDS cases reported to the World Health Organization

as of 7 July 1995. Aids Care 7:689, 1995 2. AIDS rates. MMWR 45:926, 1996 3. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance

case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR 41(RR-17):1, 1992 4. Fauci AS, Pantaleo G, Stanley S, Weissman D: Immunopathogenic mechanisms of HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 124:654, 1996 5. Turner BJ, Hecht FM, Ismail RB: CD4+ T-lymphocyte measures in the treatment of individuals infected

with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Arch Intern Med 154:1561, 1994 6. Holland GN, Gotlieb MS, Yee RD et al: Ocular disorders associated with a new severe acquired cellular immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 93:393, 1982 7. Holland GN, Pepose JS, Pettit TH et al: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: ocular manifestations. Ophthalmology 90:859, 1983 8. Rosenberg PR, Uliss AE, Friedland GH et al: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: ophthalmic manifestations in ambulatory

patients. Ophthalmology 90:874, 1983 9. Palestine AG, Rodrigues MM, Macher AM et al: Ophthalmic involvement in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 91:1092, 1984 10. Freeman WR, Lerner CW, Mines JA et al: A prospective study of the ophthalmologic findings in the acquired immune

deficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 97:133, 1984 11. Khadem M, Kalish SB, Goldsmith J et al: Ophthalmologic findings in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Arch Ophthalmol 102:201, 1984 12. Pepose JS, Holland GN, Nestor MS et al: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: pathogenic mechanisms of ocular disease. Ophthalmology 92:472, 1985 13. Kestelyn P, Van de Perre P, Rouvroy D et al: A prospective study of the ophthalmologic findings in the acquired immune

deficiency syndrome in Africa. Am J Ophthalmol 100:230, 1985 14. Mines JA, Kaplan HJ: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): the disease and its ocular manifestations. Int Ophthalmol Clin 26:73, 1986 15. Humphry RC, Weber JN, Marsh RJ: Ophthalmic findings in a group of ambulatory patients infected by human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV): A prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol 71:565, 1987 16. Fabricius EM, Jager H, Prantl F et al: AIDS of the eye: a retrospective analysis of 70 HIV-infected patients. Fortschr Ophthalmol 85:420, 1988 17. Jabs DA, Green WR, Fox R et al: Ocular manifestations of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 96:1092, 1989 18. Dennehy PJ, Warman R, Flynn JT et al: Ocular manifestations in pediatric patients with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 107:978, 1989 19. Jensen OA, Klinken L: Pathology of brain and eye in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). APMIS 97:196, 1989 20. Fabricius EM, Prantl F, Jager H et al: Incidence and pathogenesis of ocular symptoms in HIV infection. Fortschr Ophthalmol 86:461, 1989 21. Auzemery A, Queguiner P, Georges AJ et al: Ophthalmologic manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in

central Africa. Med Trop (Mars) 50:441, 1990 22. II'nitskii VA, Manuilov NN, Meleshenkova TI: Eye manifestations of AIDS in the population of the Republic of Burundi. Vestn Oftalmol 106:58, 1990 23. Gabrieli CB, Angarano G, Moramarco A et al: Ocular manifestations in HIV-seropositive patients. Ann Ophthalmol 22:173, 1990 24. Kawe LW, Renard G, Le Hoang P et al: Ophthalmologic manifestations of AIDS in an African milieu: report of 45 cases. J Fr Ophtalmol 13:199, 1990 25. Ho PCP, Farzavandi SK, Kwok SK et al: Ophthalmic complications of AIDS in Hong Kong. J Hong Kong Med Assoc 46:118, 1994 26. el Matri L, Kammoun M, Cheour M et al: Eye involvement in AIDS: the first 12 Tunisian cases. Tunis Med 70:481, 1992 27. Morinelli EN, Dugel PU, Riffenburgh R, Rao NA: Infectious multifocal choroiditis in patients with acquired immune deficiency

syndrome. Ophthalmology 100:1014, 1993 28. Iordanescu C, Matusa R, Denislam D et al: The ocular manifestations of AIDS in children. Oftalmologia 37:308, 1993 29. Ndoye NB, Sow PS, Ba EA et al: Ocular manifestations of AIDS in Dakar. Dakar Med 38:97, 1993 30. Muccioli C, Belfort R Jr, Lottenberg C et al: Achados oftalmologicos em AIDS: avaliacao de 445 casos atendidos em um

ano. Rev Assoc Med Bras 40:155, 1994 31. Seregard S: Retinochoroiditis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: findings

in consecutive post-mortem examinations. Acta Ophthalmol 72:223, 1994 32. Lewallen S, Kumwenda J, Maher D, Harries AD: Retinal findings in Malawian patients with AIDS. Br J Ophthalmol 78:757, 1994 33. Jabs DA: Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 93:623, 1995 34. Maclean H, Hall AJH, McCombe MF, Sandland AM: AIDS and the eye: a 10-year experience. Austr NZ J Ophthalmol 24:61, 1996 35. Meisler DM, Lowder CY, Holland GN: Corneal and external ocular infections

in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In Krachmer JH, Mannis

MJ, Holland EJ (eds): Cornea: Cornea and External Disease: Clinical

Diagnosis and Management, Vol 2, Chap 86, pp 1017-22. St. Louis, Mosby, 1997 36. Jabs DA: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and the eye—1996. Arch Ophthalmol 114:863, 1996 37. Jabs DA, Quinn TC: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In Pepose JS, Holland

GN, Wilhelmus KR (eds): Ocular Infection & Immunity, Chap 22, pp 289–310. St. Louis, Mosby, 1996 38. Tay-Kearney ML, Jabs DA: Ophthalmic complications of HIV infection. Med Clin North Am 80:1471, 1996 39. Nussenblatt RB, Whitcup SM, Palestine AG: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In

Uveitis, Fundamentals and Clinical Practice, 2nd ed, Chap 1, pp 186-97. St. Louis, Mosby, 1996 40. Sarraf D, Ernest JT: AIDS and the eyes. Lancet 348:525, 1996 41. Courtright P: The challenge of HIV/AIDS related eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol 80:496, 1996 42. Eller AW, Warren BB, Conti ER, Rubin TM: AIDS and the eye. Pennsylvania Med 99(suppl): 88, 1996 43. Chronister CL: Review of external ocular disease associated with AIDS and HIV infection. Optom Vis Sci 73:225, 1996 44. Currie J: AIDS and neuro-ophthalmology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 6:34, 1995 45. Miller NR: Viruses and viral diseases. In: Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical

Neuro-Ophthalmology, 4th ed, Vol 5, Pt 2, Chap 71, pp 4107–4156. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1995 46. Akduman L, Pepose JS: Anterior segment manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol 10:111, 1995 47. Kuppermann BD: Noncytomegalovirus-related chorio-retinal manifestations of the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol 10:125, 1995 48. Rajeev B, Rao NA: Ocular pathological changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol 10:168, 1995 49. Luckie A, Ai E: Pitfalls and unusual manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

in the retina. Semin Ophthalmol 10:155, 1995 50. Rickman LS, Freeman WR: Medical and virological aspects of ocular human immunodeficiency virus

infection for the ophthalmologist. Semin Ophthalmol 10:91, 1995 51. Park KL, Smith RE, Rao NA: Ocular manifestations of AIDS. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 6:82, 1995 52. McCluskey PJ, Hall AJ, Lightman S: HIV and eye disease. Med J Austr 164:484, 1995 53. Harrison TJ: Ocular complication in HIV infected individuals. Alaska Med 37:91, 1995 54. McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D: Posterior uveitis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin 35:1, 1995 55. Bernauer W: The eye and HIV. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax 84:1403, 1995 56. Armstrong RA: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the eye. Ophthalmic Physiol Optics 15(suppl 2):S42, 1995 57. Litwak AB: Non-CMV infectious chorioretinopathies in AIDS. Optom Vis Sci 72:312, 1995 58. McMullen WW, D'Amico DJ: AIDS and its ophthalmic manifestations. In Albert

DM, Jakobiec FA (eds): Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology: Clinical

Practice, Vol 5, Chap 251, pp 3102–3119. Philadelphia, WB

Saunders, 1994 59. Rao NA: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and its ocular complications. Ind J Ophthalmol 42:51, 1994 60. Rickman LS, Freeman WR: Retinal disease in the HIV infected patient. In

Ryan SJ (ed): Retina, 2nd ed, Vol 2, Medical Retina, Chap 96, pp 1571–1596. St. Louis, Mosby, 1994 61. Holland GN: AIDS: Retinal and choroidal infections. In Lewis H (ed): Medical

and Surgical Retina, Chap 35, pp 415–433. St. Louis, Mosby-Year

Book, 1994 62. Schnaudigel OE, Gumbel H, Richter R et al: Ophthalmologic manifestations in early and late stages of AIDS. Ophthalmologe 91:668, 1994 63. Glavici M: The ocular manifestations in AIDS. Oftalmologia 38:216, 1994 64. Freeman WR: Retinal disease associated with AIDS. Austr NZ J Ophthalmol 21:71, 1993 65. Mansour AM: Adnexal findings in AIDS. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 9:273, 1993 66. Gariano RF, Rickman LS, Freeman WR: Ocular examination and diagnosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. West J Med 158:254, 1993 67. McCluskey PH: HIV-related eye disease. Med J Austr 158:111, 1993 68. Cernak A, Filova I, Pont'uchova E et al: AIDS and the eye. Cesk Oftalmol 49:387, 1993 69. Banuelos Banuelos J, Gonzalez Ortiz MA, Sayagues Gomez O, Barros Aguado C: Ocular complications in AIDS patients. Rev Clin Esp 193:393, 1993 70. Nagata Y, Fujino Y, Mochizuki M: Ophthalmic manifestations in AIDS. Nippon Rinsho 51(suppl):413, 1993 71. Garweg J: Opportunistic eye diseases within the scope of HIV infection. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 202:465, 1993 72. Bonnet S, Marechal G: Ophthalmological involvement in AIDS. Rev Med Liege 48:91, 1993 73. Dunn JP, Holland GN: Human immunodeficiency virus and opportunistic ocular infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 6:909, 1992 74. Holland GN: Medical treatment of retinal infections in patients with AIDS. West J Med 157:448, 1992 75. Holland GN: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and ophthalmology: the first decade. Am J Ophthalmol 114:86, 1992 76. Frangieh GT, Dugel PU, Rao NA: Ocular manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 3:228, 1992 77. Heinemann MH: Medical management of AIDS patients: ophthalmic problems. Med Clin North Am 76:83, 1992 78. Blumenkranz MS, Penneys NS: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and the eye. Dermatol Clin 10:777, 1992 79. Siwicka R: Ocular manifestations in AIDS. Klin Oczna 94:309, 1992 80. Ugen KE, McCallus DE, Von Feldt JM et al: Ocular tissue involvement in HIV infection: immunological and pathological

aspects. Immunol Res 11:141, 1992 81. Morinelli EN, Dugel PU, Lee M et al: Opportunistic intraocular infections in AIDS. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 90:97, 1992 82. de Smet MD, Nussenblatt RB: Ocular manifestations of AIDS. JAMA 266:3019, 1991 83. Keane JR: Neuro-ophthalmologic signs of AIDS. Neurology 41:841, 1991 84. Friedman DI: Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurol Clin 9:55, 1991 85. Martenet AC: Unusual ocular lesions in AIDS. Int Ophthalmol 14:359, 1990 86. Bernauer W, Daicker B: HIV patient and eyes. J Suisse Med 120:888, 1990 87. Kestelyn P: Ocular problems in AIDS. Int Ophthalmol 14:165, 1990 88. Lund OE, Klauss V, Scheiffarth OF: AIDS and the eye. Fortschr Ophthalmol 87(suppl):S94, 1990 89. Holtmann HW: AIDS and ophthalmology. Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena) 84:919, 1990 90. Marsh RJ: Ocular manifestations of AIDS. Br J Hosp Med 42:224, 1989 91. Shuler JD, Engstrom RE, Holland GN: External ocular disease and anterior segment disorders associated with

AIDS. Int Ophthalmol Clin 29:98, 1989 92. Culbertson WW: Infections of the retina in AIDS. Int Ophthalmol Clin 29:108, 1989 93. O'Donnell JJ, Jacobson MA: Cotton-wool spots and cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS. Int Ophthalmol Clin 29:105, 1989 94. Boguszakova J, Stankova M: Eye disorders in AIDS. Cesk Oftalmol 45:380, 1989 95. Newsome DA: Noninfectious ocular complications of AIDS. Int Ophthalmol Clin 29:95, 1989 96. Vedy J, Queguiner P, Auzemery A et al: Ophthalmologic manifestations of AIDS in Africa. Rev Int Trach Pathol Ocul Trop Subtrop Sante Publique 65:107, 1988 97. Katlama C: The eye and AIDS. Ophthalmologie 3(suppl 1):5, 1989 98. Ai E, Wong KL: Ophthalmic manifestations of AIDS. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 1:53, 1988 99. Klauss V, Lund OE: Eye changes in AIDS. Fortschr Med 106:393, 1988 100. Garavelli PL, Astori MR: Ocular pathology in AIDS and related syndromes. Minerva Med 79:295, 1988 101. Zhaboedov GD, Bondareva GS: Eye manifestations of AIDS. Vestn Oftalmol 104:65, 1988 102. Petroni-Placente M, Rossazza C, Tacheix V, Le Calve M: Ophthalmological symptoms of AIDS. Bull Soc Ophtalmol France 88:123, 1988 103. Kreiger AE, Holland GN: Ocular involvement in AIDS. Eye 2 (Pt 5):496, 1988 104. Maichuk IuF: AIDS: clinical aspects of eye lesions. Oftalmologicheskii Zh 4:240, 1988 105. Fabricius EM, Jager H, Lander T et al: Eye involvement in AIDS. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 191:95, 1987 106. Dhermy P: AIDS in ophthalmology. Ann Ther Clin Ophthalmol 38:255, 1987 107. Fujikawa LS, Palestine AG, Schwartz LK, Nussenblatt RB: Ocular involvement

in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In Tasman W, Jaeger EA (eds): Duane's

Clinical Ophthalmology, Vol 2, Chap 36, pp 1–9, 1986 108. Hansen LL, Wiecha I, Witschel H: Initial diagnosis of acquired immunologic deficiency syndrome (AIDS) by

the ophthalmologist. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 191:133, 1987 109. Humphry RC, Parkin JM, Marsh RJ: The ophthalmological features of AIDS and AIDS related disorders. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 105:505, 1986 110. Grasl M, Radda T, Hutterer J: AIDS and the eye. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 187:457, 1985 111. Sonnerborg A, Julander I: AIDS and AIDS-related diseases: clinical manifestations and therapy. Lakartidningen 82:1877, 1985 112. Bass SJ: Ocular manifestations of AIDS. J Am Optometric Assoc 55:765, 1984 113. Le Hoang P, Piette JC, Rozembaum W et al: Ophthalmoscopic manifestations observed in AIDS. Bull Soc Ophtalmol France 84:377, 1984 114. Schuman JS, Friedman AH: Retinal manifestations of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS): cytomegalovirus, Candida albicans, Cryptococcus, toxoplasmosis, and Pneumocystis carinii. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 103:177, 1983 115. Karbassi M, Raizman MB, Schuman JS: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Surv Ophthalmol 36:395, 1992 116. Cole EL, Meisler DM, Calabrese LH et al: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 102:1027, 1984 117. Sandor EV, Millman A, Croxson TS et al: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus in patients at risk for AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol 101:153, 1986 118. Tschachler E, Bergstresser PR, Stingl G: HIV-related skin diseases. Lancet 348:659, 1996 119. Macher AM, Palestine A, Masur H et al: Multicentric Kaposi's sarcoma of the conjunctiva in a male homosexual

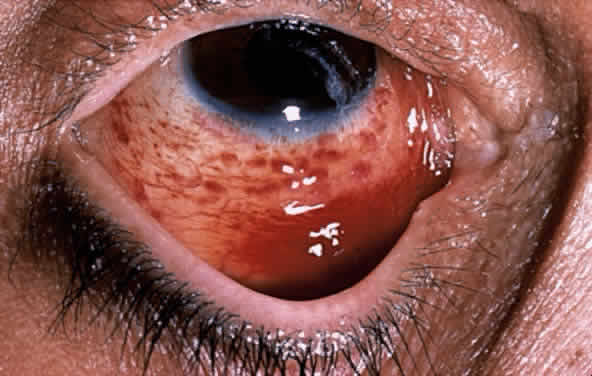

with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 90:859, 1983 120. Shuler JD, Holland GN, Miles SA et al: Kaposi sarcoma of the conjunctiva and eyelids associated with the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 107:858, 1989 121. Dugel PU, Gill PS, Frangieh GT, Rao NA: Ocular adnexal Kaposi's sarcoma in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 110:500, 1990 122. Dugel PU, Gill PS, Frangieh GT, Rao NA: Treatment of ocular adnexal Kaposi's sarcoma in acquired immune deficiency

syndrome. Ophthalmology 99:1127, 1992 123. Ghabrial R, Quivey JM, Dunn JP Jr, Char DH: Radiation therapy of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi's

sarcoma of the eyelids and conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol 110:1423, 1992 124. Hummer J, Gass JD, Huanga JW: Conjunctival Kaposi's sarcoma treated with interferon α-2a. Am J Ophthalmol 116:502, 1993 125. Offermann MK: HHV-8: a new herpesvirus associated with Kaposi's sarcoma. Trends Microbiol 4:383, 1996 126. Kohn SR: Molluscum contagiosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 105:458, 1987 127. Charles NC, Friedberg DN: Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum in acquired immune deficiency syndrome: case

report and review of the literature. Ophthalmology 99:1123, 1992 128. Robinson MR, Udell IJ, Garber PF et al: Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids in patients with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Ophthalmology 99:1745, 1992 129. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C: Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients

with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 102:1031, 1995 130. Winward KE, Curtin VT: Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with human immunodeficiency

virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 107:554, 1989 131. Kim RY, Seiff SR, Howes EL, O'Donnell JJ: Necrotizing scleritis secondary to conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma

in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 109:231, 1990 132. Kestelyn PH, Stevens AM, Ndayambaje A et al: HIV and conjunctival malignancies. Lancet 336:51, 1990 133. Ateenyl-Agaba C: Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. Lancet 345:695, 1995 134. Karp CL, Scott IU, Chang TS, Pflugfelder SC: Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia: a possible marker for human immunodeficiency

virus infection? Arch Ophthalmol 114:257, 1996 135. Muccioli C, Belfort R, Burnier M, Rao N: Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva in a patient with the acquired

immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 121:94, 1996 136. McQueen H, Dhillon B, Ironside J: Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid and the acquired immune deficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 114:219, 1996 137. Lewalen S, Shroyer KR, Keyser RB, Liomba G: Aggressive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in three young Africans. Arch Ophthalmol 114:215, 1996 138. Margo CE, Mack W, Guffey JM: Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva and human immune deficiency

virus infection. Arch Ophthalmol 114:349, 1996 139. Sandler AS, Kaplan L: AIDS lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol 8:377, 1996 140. Goldberg SH, Fieo AG, Wolz DE: Primary eyelid non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 113:216, 1992 141. Janier M, Schwartz C, Dontenwille MN, Civatte J: Hypertrichose des cils au cours du SIDA. Ann Dermatol Venereol 11:1490, 1987 142. Casanova JM, Puig T, Rubio M: Hypertrichosis of the eyelashes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol 123:1599, 1987 143. Roger D, Vaillant L, Arbeille-Brassart B et al: Quelle est la cause de l'hypertrichose ciliaire acquise du SIDA? Ann Dermatol Venereol 115:1055, 1988 144. Lopez Dupla JM, Valencia ME, Pintado V, Khamashta MA: Tricomegalia: una excepcional expression del sindrome de immunodeficiencia

adquirida. Med Clin 92:556, 1989 145. Klutman NE, Hinthorn DR: Excessive growth of eyelashes in a patient with AIDS being treated with

zidovudine. N Engl J Med 324:1896, 1991 146. Kaplan MH, Sadick NS, Talmor M: Acquired trichomegaly of the eyelashes: a cutaneous marker of acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 25:801, 1991 147. Sahai J, Conway B, Cameron D, Gaber G: Zidovudine-associated hypertrichosis and nail pigmentation in an HIV-infected

patient. AIDS 5:1395, 1991 148. Teich SA: Conjunctival microvascular changes in AIDS and AIDS-related complex. Am J Ophthalmol 103:332, 1987 149. Engstrom RE, Holland GN, Hardy WD et al: Hemorrheologic abnormalities in patients with human immunodeficiency virus

infection and ophthalmic microvasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 109:153, 1990 150. Brown HH, Glasgow BJ, Holland GN, Foos RY: Cytomegalovirus infection of the conjunctiva in AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol 106:102, 1988 151. Espana-Gregori E, Vera-Sempere FJ, Cano-Parra J et al: Cytomegalovirus infection of the caruncle in the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 117:406, 1994 152. Balmes R, Bialasiewicz AA, Busse H: Conjunctival cryptococcosis preceding human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion. Am J Ophthalmol 113:719, 1992 153. Gordon JJ, Golbus J, Kurtides ES: Chronic lymphadenopathy and Sjögren's syndrome in a homosexual

man. N Engl J Med 311:1441, 1984 154. Couderc LJ, D'Agay MF, Danon F et al: Sicca complex and infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med 147:898, 1987 155. Pflugfelder SC, Savlsow R, Ullman S: Peripheral corneal ulceration in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Am J Ophthalmol 104:542, 1987 156. Lucca JA, Farris RL, Bielory L, Caputo AR: Keratoconjunctivitis sicca in male patients infected with human immunodeficiency

virus type 1. Ophthalmology 97:1008, 1990 157. Lucca JA, Kung JS, Farris RL: Keratoconjunctivitis sicca in female patients infected with human immunodeficiency

virus. CLAO J 20:49, 1994 158. Engstrom RE, Holland GN: Chronic herpes zoster virus keratitis associated with the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 105:556, 1988 159. Silverstein BE, Chandler D, Neger R, Margolis TP: Disciform keratitis: a case of herpes zoster sine herpete. Am J Ophthalmol 123:254, 1997 160. Young TL, Robin JB, Holland GN et al: Herpes simplex keratitis in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 96:1476, 1989 161. McLeish W, Pfulugfelder SC, Course C et al: Interferon treatment of herpetic keratitis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 109:93, 1990 162. Rosenwasser GOD, Greene WH: Simultaneous herpes simplex types 1 and 2 keratitis in acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 113:102, 1992 163. Hodge WG, Margolis TP: Herpes simplex virus keratitis among patients who are positive or negative

for human immunodeficiency virus: an epidemiologic study. Ophthalmology 104:120, 1997 164. Wilhelmus KR, Font RL, Lehmann RP, Cernoch PL: Cytomegalovirus keratitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 114:869, 1996 165. Ticho BH, Urban RC Jr, Safran MJ, Saggau DD: Capnocytophaga keratitis associated with poor dentition and human immunodeficiency

virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 109:352, 1990 166. Nanda M, Pflugfelder SC, Holland S: Fulminant pseudomonal keratitis and scleritis in human immunodeficiency

virus-infected patients. Arch Ophthalmol 109:503, 1991 167. Maguen E, Salz JJ, Nesburn AB: Pseudomonas corneal ulcer associated with rigid, gas-permeable, daily-wear

lenses in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Ophthalmol 113:336, 1992 168. Hemady RK, Griffin N, Aristimuno B: Recurrent corneal infections in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Cornea 12:266, 1993 169. Aristimuno B, Nirankari VS, Hemady RK, Rodrigues MM: Spontaneous ulcerative keratitis in immunocompromised patients. Am J Ophthalmol 115:202, 1993 170. Santos C, Parker J, Dawson C, Ostler B: Bilateral fungal corneal ulcers in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Am J Ophthalmol 102:118, 1986 171. Parrish CM, O'Day DM, Hoyle TC: Spontaneous fungal corneal ulcer as an ocular manifestation of AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol 104:302, 1987 172. Bryan RT: Microsporidiosis as an AIDS-related opportunistic infection. Clin Infect Dis 21(suppl 1):562, 1995 173. Lowder CY, Meisler DM, McMahon JT et al: Microsporidia infection of the cornea in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency

virus. Am J Ophthalmol 109:242, 1990 174. Cali A, Meisler DM, Rutherford I et al: Corneal microsporidiosis in a patient with AIDS. Am J Trop Med Hygiene 44:463, 1991 175. Cali A, Meisler DM, Lowder CY et al: Corneal microsporidiosis: characterization and identification. J Protozool 38:215S, 1991 176. Davis RM, Font RL, Keisler MS, Shadduck JA: Corneal microsporidiosis: a case report including ultrastructural observations. Ophthalmology 97:953, 1990 177. Friedberg DN, Stenson SM, Orenstein JM et al: Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 108:504, 1990 178. Didier ES, Didier PJ, Friedberg DN et al: Isolation and characterization of a new human microsporidian, Encephalitozoon

hellem (n. sp.), from three AIDS patients with keratoconjunctivitis. J Infect Dis 163:617, 1991 179. Yee RW, Tio FO, Martinez JA et al: Resolution of microsporidial epithelial keratopathy in a patient with AIDS. Ophthalmology 98:196, 1991 180. Metcalfe TW, Doran RM, Rowlands PL et al: Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in a patient with AIDS. Br J Ophthalmol 76:177, 1992 181. Diesenhouse MC, Wilson LA, Corrent GF et al: Treatment of microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis with topical fumagillin. Am J Ophthalmol 115:293, 1993 182. McCluskey PJ, Goonan PV, Marriott DJ, Field AS: Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in AIDS. Eye 7:80, 1993 183. Schwartz DA, Visvesvara GS, Diesenhouse MC et al: Pathologic features and immunofluorescent antibody demonstration of ocular

microsporidiosis (Encephalitozoon hellem) in seven patients with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 115:285, 1993 184. Rosberger DF, Serdarevic ON, Erlandson RA et al: Successful treatment of microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis with topical

fumagillin in a patient with AIDS. Cornea 12:261, 1993 185. Lowder CY: Ocular microsporidiosis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 33:145, 1993 186. Gunnarsson G, Hurlbut D, DeGirolami PC et al: Multiorgan microsporidiosis: Report of five cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 21:37, 1995 187. Lowder CY, McMahon JT, Meisler DM et al: Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis caused by Septata intestinalis in a

patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 121:715, 1996 188. Shah GK, Pfister D, Probst LE et al: Diagnosis of microsporidial keratitis by confocal microscopy and the chromotrope

stain. Am J Ophthalmol 121:89, 1996 189. Holland GN, Tufail A, Jordan MC: Cytomegalovirus disease. In Pepose JS, Holland

GN, Wilhelmus KR (eds): Ocular Infection and Immunity, Chap 81, pp 1088–1120. St. Louis, Mosby, 1996 190. Dunn JP, Jabs DA: Cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS: natural history, diagnosis, and

treatment. AIDS Clin Rev 99, 1995-1996 191. Foster DJ, Dugel PU, Frangieh GT et al: Rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis in the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 110:341, 1990 192. Margolis TP, Lowder CY, Holland GN et al: Varicella-zoster virus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 112:119, 1991 193. Engstrom RE Jr, Holland GN, Margolis TP et al: The progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome: a variant of necrotizing

herpetic retinopathy in patients with AIDS. Ophthalmology 101:1488, 1994 194. Short GA, Margolis TP, Kuppermann DB et al: A PCR based assay for the diagnosis of AIDS associated VZV retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 123:157, 1997 195. Cunningham ET Jr, Short GA, Irvine AR et al: AIDS-associated herpes simplex virus retinitis: clinical description and

use of a polymerase chain reaction-based assay as a diagnostic tool. Arch Ophthalmol 114:834, 1996 196. Rummelt V, Rummelt C, Gahn G et al: Triple retinal infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1, cytomegalovirus, and

herpes simplex type 1: light and electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization. Ophthalmology 101:270, 1994 197. Holland GN, Engstrom RE, Glasglow BJ et al: Ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 106:653, 1988 198. Grossniklaus HE, Specht CS, Allaire G, Leavitt JA: Toxoplasma gondii retinochoroiditis and optic neuritis in acquired immune

deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 97:1342, 1990 199. Gagliuso DJ, Teich SA, Friedman AH, Orellana J: Ocular toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 88:63, 1990 200. Cochereau-Massin I, LeHoang P, Lautier-Frau M et al: Ocular toxoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Am J Ophthalmol 114:130, 1992 201. Berger BB, Egwuagu CE, Freeman WR, Wiley CAA: Miliary toxoplasmic retinitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 111:373, 1993 202. Zaidman GW: Neurosyphilis and retrobulbar neuritis in a patient with AIDS. Ann Ophthalmol 18:260, 1986 203. Johns DR, Tierney M, Felsenstein D: Alteration in the natural history of neurosyphilis by concurrent infection

with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 316:1569, 1987 204. Berry CD, Hooton TM, Collier AC, Lukehart SA: Neurologic relapse after benzathine penicillin therapy for syphilis in

a patient with HIV infection. N Engl J Med 316:1587, 1987 205. Carter JB, Hamill RJ, Matoba AY: Bilateral syphilitic optic neuritis in a patient with a positive test for

HIV. Arch Ophthalmol 105:1485, 1987 206. Kleiner RC, Najarian L, Levenson J, Kaplan HJ: AIDS complicated by syphilis can mimic uveitis and Crohn's disease. Arch Ophthalmol 105:1486, 1987 207. Zambrano W, Perez GM, Smith JL: Acute syphilitic blindness in AIDS. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 7:1, 1987 208. Radolf JB, Kaplan RP: Unusual manifestations of secondary syphilis and abnormal humoral immune

response to Treponema pallidum antigens in a homosexual man with asymptomatic

human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 18:423, 1988 209. Passo MS, Rosenbaum JT: Ocular syphilis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 106:1, 1988 210. Richards BW, Hessburg TJ, Nussbaum JN: Recurrent syphilitic uveitis. N Engl J Med 320:62, 1989 211. Levy JH, Liss RA, Maguire AM: Neurosyphilis and ocular syphilis in patients with concurrent human immunodeficiency

virus infection. Retina 9:175, 1989 212. Becerra LI, Ksiazek SM, Savino PJ et al: Syphilitic uveitis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and non-infected

patients. Ophthalmology 96:1727, 1989 213. Gass JBM, Braunstein RA, Chenoweth RG: Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. Ophthalmology 97:1288, 1990 214. McLeish WM, Pulido JS, Holland S et al: The ocular manifestations of syphilis in the human immunodeficiency virus

type 1--infected host. Ophthalmology 97:196, 1990 215. Tamesis RR, Foster CS: Ocular syphilis. Ophthalmology 97:1281, 1990 216. Pillai S, DePaolo F: Bilateral panuveitis, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis in a patient

with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 114:773, 1992 217. Halperin LS: Neuroretinitis due to seronegative syphilis associated with human immunodeficiency

virus. J Clin Neuroophthalmology 12:171, 1992 218. Macher A, Rodrigues MM, Kaplan W et al: Disseminated bilateral chorioretinitis due to Histoplasma capsulatum in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 92:1159, 1985 219. Kurosawa A, Pollack SC, Collins MP et al: Sporothrix schenckii endophthalmitis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Ophthalmol 106:376, 1988 220. Davis JL, Nussenblatt RB, Bachman DM et al: Endogenous bacterial retinitis in AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol 107:613, 1989 221. Shivaram U, Cash M: Purpura fulminans, metastatic endophthalmitis, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic

purpura in an HIV-infected patient. NY State J Med 92:313, 1992 222. Pavan PR, Margo CE: Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Bipolaris hawaiienisis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 116:644, 1993 223. Tufail A, Weisz JM, Holland GN: Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis as a complication of intravenous therapy

for cytomegalovirus retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 114:879, 1996 224. Glasgow BJ, Engstrom RE Jr, Holland GN et al: Bilateral endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis associated with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 114:873, 1996 225. Walton CR, Wilson J, Chan C-C: Metastatic choroidal abscess in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 114:880, 1996 226. Rehder JR, Burnier M, Pavesio CE et al: Acute unilateral toxoplasmic iridocyclitis in an AIDS patient. Am J Ophthalmol 106:740, 1988 227. Charles NC, Boxrud CA, Small EA: Cryptococcosis of the anterior segment in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 99:813, 1992 228. Chang M, van der Horst CM, Olney MS, Peiffer RL: Clinicopathologic correlation of ocular and neurologic findings in AIDS: case

report. Ann Ophthalmol 18:105, 1986 229. Altman EM, Centeno LV, Mahal M, Bielory L: AIDS-associated Reiter's syndrome. Ann Allergy 72:307, 1994 230. Berenbaum F, Duvivier C, Prier A, Kaplan G: Successful treatment of Reiter's syndrome in a patient with AIDS with

methotrexate and corticosteroids. Br J Rheumatol 35:295, 1996 231. Shafran SD, Deschenes J, Miller M et al: Uveitis and pseudojaundice during a regimen of clarithromycin, rifabutin, and

ethambutol. N Engl J Med 330:438, 1994 232. Saran BR, Maguire AM, Nichols C et al: Hypopyon uveitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome treated

for systemic Mycobacterium avium complex infection with rifabutin. Arch Ophthalmol 112:1159, 1994 233. Tseng AL, Walmsley SL: Rifabutin-associated uveitis. Ann Pharmacother 29:1149, 1995 234. The HPMPC Peripheral Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Trial: Parenteral cidofovir

for cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS: a randomized, controlled

trial: studies of Ocular complications of AIDS Research Group

in Collaboration with the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Ann Intern Med 126:264, 1997 235. Rahhal FM, Arevalo JF, Munguia D et al: Intravitreal cidofovir for the maintenance treatment of cytomegalovirus

retinitis. Ophthalmology 103:1078, 1996 236. Ullman S, Wilson RP, Schwartz L: Bilateral angle-closure glaucoma in association with the acquired immune

deficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 101:419, 1986 237. Williams AS, Williams FC, O'Donnell JJ: AIDS presenting as acute glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 106:311, 1988 238. Nash RW, Lindquist TD: Bilateral angle-closure glaucoma associated with uveal effusion: presenting

sign of HIV infection. Surv Ophthalmol 36:255, 1992 239. Krzystolik MG, Kuperwasser M, Low RM, Dreyer EB: Anterior-segment ultrasound biomicroscopy in a patient with AIDS and bilateral

angle-closure glaucoma secondary to uveal effusions. Arch Ophthalmol 114:878, 1996 240. Gass JDM: Uveal effusion syndrome: A new hypothesis concerning pathogenesis and technique

of surgical treatment. Retina 3:159, 1983 241. Freeman WR, Chen A, Henderly DE et al: Prevalence and significance of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related

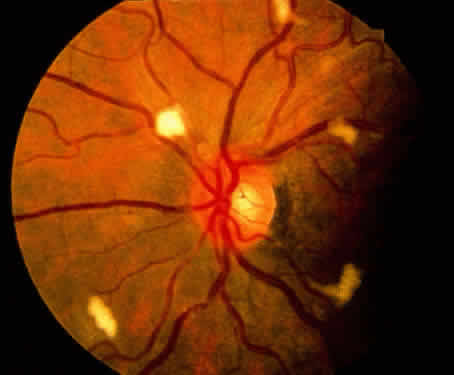

retinal microvasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 107:229, 1989 242. Glasgow BJ, Weisberger AK: A quantitative and cartographic study of retinal microvasculopathy in acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 118:46, 1994 243. Newsome DA, Green WR, Miller ED et al: Microvascular aspects of acquired immune deficiency syndrome retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 98:590, 1984 244. Tenhula WN, Xu S, Madigan MC et al: Morphometric comparisons of optic nerve axon loss in acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 113:14, 1992 245. Sadun AA, Pepose JS, Madigan MC et al: AIDS-related optic neuropathy: a histological, virological and ultrastructural

study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 233:387, 1995 246. Latkany PA, Holopigian K, Lorenzo-Latkany M, Seiple W: Electroretinographic and psychophysical findings during early and late

stages of human immunodeficiency virus infection and cytomegalovirus retinitis. Ophthalmology 104:445, 1997 247. Quiceno JI, Capparelli E, Sadun AA et al: Visual dysfunction without retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 113:8, 1992 248. Plummer DJ, Sample PA, Arevalo JF et al: Visual field loss in HIV-positive patients without infectious retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 122:542, 1996 249. Gonzalez CR, Wiley CA, Arevalo JF et al: Polymerase chain reaction detection of cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency

virus-1 in the retina of patients with acquired immune deficiency

syndrome with and without cotton-wool spots. Retina 16:305, 1996 250. Freeman WR: New developments in the treatment of CMV retinitis. Ophthalmology 103:999, 1996 251. Jabs DA: Treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Ann Intern Med 125:144, 1996 252. Engstrom RE Jr, Holland GN: Local therapy for cytomegalovirus retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 120:376, 1995 253. Cunningham ET Jr: New Treatments for CMV retinitis in patients with AIDS. West J Med 166:138, 1997 254. Moorthy RS, Smith RE, Rao NA: Progressive ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 115:742, 1993 255. Elkins BS, Holland GN, Opremcak EM et al: Ocular toxoplasmosis misdiagnosed as cytomegalovirus retinopathy in immunocompromised

patients. Ophthalmology 101:499, 1994 256. Wei ME, Campbell SH, Taylor C: Precipitous visual loss secondary to optic nerve toxoplasmosis as an unusual

presentation of AIDS. Austr NZ J Ophthalmol 24:75, 1996 257. Lopez JS, de Smet MD, Masur H et al: Orally administered 566C80 for treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis in a patient

with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 113:331, 1992 258. Schlossberg D, Morad Y, Krouse TB et al: Culture-proved disseminated cat-scratch disease in acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Arch Intern Med 149:1437, 1989 259. Wong MT, Dolan MJ, Lattuada CP Jr et al: Neuroretinitis, aseptic meningitis, and lymphadenitis associated with Bartonella (Rochalimaea) henselae infection in immunocompetent patients and patients infected with human

immunodeficiency virus type I. Clin Infect Dis 21:352, 1995 260. Rao NA, Zimmerman PL, Boyer D et al: A clinical, histological, and electron microscopic study of Pneumocystis carinii choroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol 107:218, 1989 261. Shami MJ, Freeman W, Friedberg D et al: A multicenter study of Pneumocystis choroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 112:15, 1991 262. Kestelyn P, Taelman H, Bogaerts J et al: Ophthalmic manifestations of infection with Cryptococcus neoformans in

patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 116:721, 1993 263. Muccioli C, Belfort R Jr, Rao N: Limbal and choroidal cryptococcus infection in the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 120:539, 1995 264. Saran BR, Pomilla PV: Retinal vascular nonperfusion and retinal neovascularization as a consequence

of cytomegalovirus retinitis and cryptococcal choroiditis. Retina 16:510, 1996 265. Schanzer MC, Font RL, O'Malley RE: Primary ocular malignant lymphoma associated with the acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome. Ophthalmology 98:88, 1991 266. Stanton CA, Sloan DB III, Slusher MM, Greven CM: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related primary intraocular lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol 110:1614, 1992 267. Matzkin DC, Slamovits TL, Rosenbaum PS: Simultaneous intraocular and orbital non-Hodgkin lymphoma in acquired immune

deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 101:850, 1994 268. Fujikawa LS, Schwartz LK, Rosenbaum EH: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome associated with Burkitt's lymphoma

presenting with ocular findings. Ophthalmology 90(suppl):50, 1983 269. Tien DR: Large cell lymphoma in AIDS. Ophthalmology 98:412, 1991 270. Antle CM, White VA, Horsman DE, Rootman J: Large cell orbital lymphoma in a patient with acquired immune deficiency

syndrome: case report and review. Ophthalmology 97:1484, 1990 271. Mansour AM: Orbital findings in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 110:706, 1990 272. Brooks HL Jr, Downing J, McClure JA, Engel HM: Orbital Burkitt's lymphoma in a homosexual man with acquired immune

deficiency. Arch Ophthalmol 102:1533, 1984 273. Font RL, Laucirica R, Patrimely JR: Immunoblastic B-cell malignant lymphoma involving the orbit and maxillary

sinus in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 100:966, 1993 274. Kronish JW, Johnson TE, Gilberg SM et al: Orbital infections in patients with human immunodeficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 103:1483, 1996 275. Vitale AT, Spaide RF, Warren FA et al: Orbital aspergillosis in an immunocompromised host. Am J Ophthalmol 113:725, 1992 276. Cahill KV, Hogan CD, Koletar SL, Gersman M: Intraorbital injection of amphotericin B for palliative treatment of Aspergillus

orbital abscess. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 10:276, 1994 277. Friedberg DN, Warren FA, Lee MH et al: Pneumocystis carinii of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol 113:595, 1992 278. Cano-Parra J, Espana E, Esteban M et al: Pseudomonas conjunctival ulcer and secondary orbital cellulitis in a patient

with AIDS. Br J Ophthalmol 78:72, 1994 279. Cheung SW, Lee KC, Cha I: Orbitocerebral complications of Pseudomonas sinusitis. Laryngoscope 102:1385, 1992 280. Meyer RD, Gaultier Cr, Yamashita JT et al: Fungal sinusitis in patients with AIDS: report of 4 cases and review of

the literature. Medicine 73:69, 1994 281. Blatt SP, Lucey DR, DeHoff D, Zellmer RB: Rhinocerebral zygomycosis in a patient with AIDS. J Infect Dis 164:215, 1991 282. Benson WH, Linberg JV, Weinstein GW: Orbital pseudotumor in a patient with AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol 105:697, 1988 283. Fabricius EM, Hoegl I, Pfaeffl W: Ocular myositis as first presenting symptom of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection

and its response to high-dose cortisone treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 75:696, 1991 284. Gross FJ, Waxman JS, Rosenblatt MA et al: Eosinophilic granuloma of the cavernous sinus and orbital apex in an HIV-positive

patient. Ophthalmology 96:462, 1989 285. Singer MA, Warren F, Accardi F et al: Adenocarcinoma of the stomach confirmed by orbital biopsy in a patient

seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Ophthalmol 110:707, 1990 286. Ormerod LD, Rhodes RH, Gross SA et al: Ophthalmic manifestations of acquired immune deficiency syndrome-associated

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ophthalmology 103:889, 1996 287. Englund JA, Baker CJ, Raskino C et al: Clinical and laboratory characteristics of a large cohort of symptomatic, human

immunodeficiency virus-infected infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 15:1025, 1996 288. Baumal CR, Levin AV, Kavalec CC et al: Screening for cytomegalovirus retinitis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 150:1186, 1996 289. Bremond-Gignac D, Aron-Rosa D, Rohrlich P et al: Cytomegalovirus retinitis in children with AIDS acquired through materno-fetal

transmission. J Fr Ophtalmol 18:91, 1995 290. Falloon J, Eddy J, Wiener L et al: Human immunodeficiency virus infection in children. J Pediatr 144:1, 1989 291. Wiznia AA, Lambert G, Pavlakis S: Pediatric HIV infection. Med Clin North Am 80:1309, 1996 292. Marion MW, Wiznia AA, Hutcheon RG, Rubenstein A: Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type II (HTLV-III) embryopathy. Am J Dis Child 140:638, 1986 293. Marion MW, Wiznia AA, Hutcheon G, Rubinstein A: Fetal AIDS syndrome score: correlation between severity of dysmorphism

and age at diagnosis of immunodeficiency. Am J Dis Child 141:429, 1987 294. Whitcup SM, Butler KM, Caruso R et al: Retinal toxicity in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children treated

with 2',3'-dideoxyinosine. Am J Ophthalmol 113:1, 1992 295. Whitcup SM, Dastgheib K, Nussenblatt RB et al: A clinicopathologic report of the retinal lesions associated with didanosine. Arch Ophthalmol 112:1594, 1994 296. Wilhelmus KR, Keener MJ, Jones DB, Font RL: Corneal lipidosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 119:14, 1995 297. Shah GK, Cantrill HL, Holland EJ: Vortex keratopathy associated with atovaquone. Am J Ophthalmol 120:669, 1995 |