|

|

Chapter 22: Low Vision

Author:

Low Vision

In every subspecialty of ophthalmology, the patient with impaired vision represents a challenge in management. Whether reduced vision is temporary or permanent, it is the consequence of an eye disorder and, as such, is the responsibility of the ophthalmologist and optometrist. If the outcome of optimal medical and surgical intervention is diminished functional vision, the patient needs vision rehabilitation. No person with low vision should have to search far and wide for low-vision care. Some level of care should be integrated into every ophthalmic practice whether it is on-site or referral to a low-vision center.

Low-vision patients typically have impaired visual performance, ie, visual acuity is not correctable with conventional glasses or contact lenses. They may have cloudy vision, constricted fields, or large scotomas. There may be additional functional complaints: glare sensitivity, abnormal color perception, difficulty with diminished contrast. Some patients have diplopia. A frequent complaint is confusion from overlapping but dissimilar images from each eye.

The term "low vision" covers a wide range. A person in the early stages of an eye disease may have near-normal vision. Others may have moderate to severe loss. All low-vision patients have some degree of useful vision even though they might have a profound loss. They should not be considered "blind" unless their level of function is near-blind. Performance varies with each individual.

In the United States, over 6 million persons are visually impaired but not classified as legally blind.* Over 75% of patients seeking treatment are age 65 or older. Age-related macular degeneration accounts for an increasing number of cases. Other common causes of low vision are complicated cataract, corneal dystrophy, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, optic atrophy, stroke, degenerative myopia, and retinitis pigmentosa.

Effective low-vision intervention starts as soon as the patient experiences difficulty performing ordinary tasks. A treatment plan should consider the level of function, realistic goals for intervention, and the varieties of devices that could be helpful. Patients must face the fact that impaired vision is usually progressive. The sooner they adapt to low-vision devices, the sooner they can adjust to the new techniques of using their vision. Low-vision evaluation should never be delayed unless the person is undergoing active medical or surgical treatment.

Visual performance can be improved by the use of optical and nonoptical devices. The general term for corrective devices is "low-vision aids." In this chapter, the emphasis will be on assessment techniques, descriptions of useful devices, and a discussion of some of the functional aspects of common eye diseases.

MANAGEMENT OF THE PATIENT WITH LOW VISION

Comprehensive management includes (1) history of onset, and the effect of the eye condition on daily life; (2) examination for best corrected acuity, visual fields, contrast sensitivity, color perception, and glare sensitivity if it pertains to the patient's symptoms; (3) evaluation of near vision and reading skills; (4) selection and prescription (or lending) of aids that accomplish task objectives; (5) instruction in correct use and application of devices; and (6) follow-up to reinforce new patterns.

1. HISTORY TAKING

Specific features of the onset, treatments given, and current medications should be verified. Patients' responses indicate their understanding of their condition. Are there unrealistic or unreasonable attitudes? Does the person understand what can be achieved with low-vision rehabilitation? It is helpful to list a number of common daily activities the patient can no longer perform efficiently (Table 22-1). From this list it is possible to arrive at realistic objectives for that person.

2. EXAMINATION

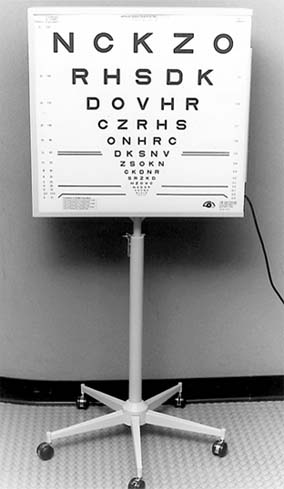

The patient should not have pupillary dilation before a low-vision evaluation. Refractive status should be confirmed to rule out a significant change. A patient may have become myopic (cataract) or astigmatic (corneal or cataract surgery). The most accurate acuity test is the Early-Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart (Figure 22-1), which has 14 five-letter lines of 0.1 log unit size difference and a convenient metric or Snellen conversion table. A 4 meter test distance is used when acuity is 20/20 to 20/200; a 2 meter distance for acuities less than 20/200 but 20/400 or better; and the 1 meter distance for acuities less than 20/400. The ETDRS chart makes obsolete the imprecise expression "finger counting only."

Figure 22-1: Lighthouse modification of the Ferris-Bailey ETDRS chart in a movable light box.

Projector charts are not recommended for testing subnormal vision because of low contrast and insufficient letter choice at low acuities. Any Snellen chart may be hand-held at 10 feet or less.

The dominant eye and preferred eye should be noted.

The Amsler grid is the traditional test for evaluating the central field. Although it is relatively insensitive, it can be used to advantage in low vision, particularly to identify the dominant eye. At the test distance of 33 cm, the patient should first look at the chart binocularly. ("Can you see the dot?") Observe for eye or head turn. If the dot is seen, the patient is using either a viable macular area or an eccentric viewing region. An eye turn or head tilt may confirm this. Ask the patient to report distortion or blank areas seen binocularly. Then check the grid monocularly and again ask the patient to report seeing the center fixation dot and any distortion or scotoma. If the grid is presented in this manner, the patient understands what is expected and the test can provide helpful data. For example, if a large scotoma in the dominant eye overrides the better nondominant eye, the patient probably will require occlusion of the dominant eye. If the dominant eye "fills in" the defect of the poorer eye, the patient can benefit from binocular correction.

Tests of contrast express the functional level of retinal sensitivity more accurately than any other test, including acuity. Of the available tests for contrast sensitivity, the test using sine wave gratings (Vistech) covers the greatest number of retinal receptor channels. The resulting curve measures the contrast levels attained in each of five channels covering low, middle, and high contrast. Contrast sensitivity is a predictor of the retina's response to magnification. Regardless of acuity, if contrast is subthreshold, the patient is unlikely to respond to optical magnification. The contrast curve is analogous to the curve produced in audiometry (pitch and volume).

the test using sine wave gratings (Vistech) covers the greatest number of retinal receptor channels. The resulting curve measures the contrast levels attained in each of five channels covering low, middle, and high contrast. Contrast sensitivity is a predictor of the retina's response to magnification. Regardless of acuity, if contrast is subthreshold, the patient is unlikely to respond to optical magnification. The contrast curve is analogous to the curve produced in audiometry (pitch and volume).

Simple color identification tests are done if the patient's complaints include difficulty with color cues.

3. NEAR VISION

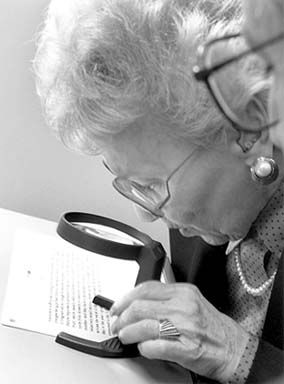

Near vision may be evaluated with a combination of single-letter tests (Figure 22-2) and graded text. Single letters and short words are presented first to establish near acuity. Graded text is presented after the function tests to establish reading skills with the selected optical devices.

Figure 22-2: Low-vision spectacle aid. Patient demonstrates close reading distance (with lenticular spectacle) but with both hands free to hold reading material.

4. SELECTION OF DEVICES & PATIENT INSTRUCTION

The dioptric range is selected from the outcome of acuity tests, modified by the results of the Amsler grid and contrast sensitivity tests. A rule of thumb for the starting power is to calculate the reciprocal of a visual acuity-eg, an acuity of 20/160 (160/20) suggests a starting lens of 8 diopters. Keep in mind that visual acuity is not a particularly sensitive measure of function. Scotomas within the reading field and the contrast sensitivity of the paramacular retina have a greater influence on ability to read through an optical lens.

After the dioptric range has been agreed upon, the three major categories of devices are presented in sequence in the selected power.

5. INSTRUCTION

Part of effective management of every low-vision patient is skilled instruction in using a device. Attention should be paid to daily living activities, which can be complemented by low-vision lenses, but may also require referral to an agency for the visually impaired.

The patient uses the various devices under the supervision of an instructor until proficiency is achieved. During the instruction time, mechanics of the aids are reviewed, questions are answered, and goals reexamined. The patient is allowed ample time to learn correct techniques in one or more sessions, and possibly a loaner lens for home or job trial. Older patients usually need more adaptation time and reinforcement than younger or congenitally impaired persons.

Practitioners and staff benefit from training programs to learn how to manage a low-vision patient in the office. Basic setups for incorporating low vision into a practice are reviewed in a number of publications.

Instruction is the key to success in vision rehabilitation. Over 90% of patients succeed with instruction, whereas a 50% success rate (no better than chance) results from prescribing an aid without training.

6. FOLLOW-UP

In two to three weeks the patient's progress is reviewed, adjustments are made, and prescriptions are finalized. If minor problems arise within the first few days after the appointment they can usually be resolved by telephone.

LOW-VISION AIDS

There are five types of low-vision aids: (1) convex lens aids such as spectacle, hand-held, and stand-mounted magnifiers; (2) telescopic systems, either spectacle-mounted or hand-held; (3) nonoptical (adaptive) devices such as large print, lighting, reading stands, marking devices, talking clocks, timers, and scales; (4) tints and filters, including antireflective lenses; and (5) electronic reading systems such as closed-circuit television reading machines, optical print scanners, computers with large print programs, and computers equipped with voice commands to access the programs.

1. CONVEX LENS AIDS

Spectacles and hand and stand magnifiers are prescribed for over 90% of patients. Various mountings have inherent advantages and disadvantages. If the patient uses spectacles, reading material must be held at the focal distance of the lens, eg, 10 cm for a 10-diopter lens. The stronger the lens, the shorter the reading distance, which tends to obstruct light (Figure 22-2) The advantage of spectacles is that both hands remain free to hold the reading material. Lamps with flexible arms can be adjusted for uniform lighting.

Patients who have binocular potential may use spectacles in the 4- to 14-diopter range with base-in prism to aid convergence. Above 14 diopters, a monocular sphere must be used for the better eye.

Hand magnifiers are convenient for shopping, reading dials and labels, identifying money, etc (Figure 22-3). They are often used by older people in conjunction with their reading glasses to enlarge print. The advantage of the hand-held lens is a greater working space between the eye and lens. Holding a lens, however, may be a disadvantage for a trembling hand or stiff joints. Hand magnifiers are available from 4 to 68 diopters.

Figure 22-3: Hand magnifiers of varius types and strengths.

Stand magnifiers are convex lenses mounted on a rigid base whose height is related to the power of the lens, eg, a 10 diopter lens is just under 10 cm from the page (Figure 22-4). Because the lens mounting may block light, a lens with a battery-powered light may be the best choice. Patients with corneal and lens pathology may not be able to tolerate the glare from an illuminated device.

Figure 22-4: A woman with macular degeneration uses a fixed-focus stand magnifier. Her hand tremor prevented her from using a hand magnifier.

2. TELESCOPIC SYSTEMS

Telescopic systems are the only devices that can be focused from infinity to near. For low vision, the simplest device is the hand-held monocular for short-term viewing, particularly of signs. For patients with vocational or hobby interests, Galilean or Keplerian telescopes (internal prism systems) in a spectacle frame are practical (Figure 22-5). A recent development is a monocular autofocus telescope. The practical limit of power for hand-held units is 2-8×. Spectacle telescopes are difficult to use above 6×. All telescopes share the disadvantage of a small field diameter and shallow depth of field.

Figure 22-5: Low-vision telescopes. A: Hand-held monocular telescope. B: Spectacle-mounted Galilean focusable telescope.

3. NONOPTICAL (ADAPTIVE) DEVICES

There are many practical items that augment or replace visual aids. They are traditionally called "nonoptical devices," though "adaptive aids" is probably a better term. In daily life, difficulty reading is not the only frustrating experience for the low-vision person. Cooking, setting thermostats and stove dials, measuring, reading a scale, putting on makeup, selecting the correct illumination, identifying paper money, and playing cards are only a few things that sighted people take for granted. A catalog from The Lighthouse lists practical articles for every facet of daily life. Patients and family members appreciate it as a handout to review at home.

4. TINTS & COATINGS

Many low-vision patients complain of poor contrast and glare, which particularly hampers getting around by themselves. A basic approach is to consider the effect of short-wave light on cloudy media and to remember that contrast is also affected by time of day, weather, and textures and colors in the surroundings. As a rule, light or medium gray lenses are prescribed to reduce light intensity. To improve contrast and reduce the effect of short-wave light rays, amber or yellow lenses are suggested. Companies such as Corning and NoIR design and manufacture lenses specifically for low-vision patients. An additional antireflective coating should be considered for patients who are mildly glare sensitive.

5. ELECTRONIC READING SYSTEMS

Electronic devices are the only ones that encour- age a natural reading posture. A closed-circuit television reading machine (CCTV) consists of a high-resolution television monitor with a built-in camera with a zoom lens, an accessory lamp, and an X-Y reading platform. The patient sits comfortably in front of the screen, moving the print back and forth on the platform. Magnification from 1.5× to 45× is possible with adjustable font sizes, and the background can be reversed from white to dark gray. Some models have choices of print colors. Recent developments include a hand-held camera, the Mouse-Cam, that can be carried around and plugged into any TV; computers with voice output and scrolling of text; and optical scanners that can read text aloud. Standard personal computers can be easily modified for large print programs. Laptop computers have insufficient contrast and screen size for the average low-vision patient.

THE EFFECT OF THE EYE DISORDER

Treatment plans should take into account the effect of the eye disorder on both visual acuity and visual field. The type and strength of visual aid are influenced by the type and extent of the deficit.

Diseases resulting in low vision can be classified in four categories: (1) blurred or hazy vision throughout the visual field, characteristic of cloudy media (cornea, lens, lens capsule, vitreous); (2) impaired resolution without central scotoma with normal peripheral retina, characteristic of macular edema or albinism; (3) central scotomas, characteristic of degenerative, congenital, or inflammatory macular disorders, and the cecocentral scotoma of optic nerve disease; and (4) peripheral scotomas, typical of retinitis pigmentosa, advanced glaucoma, stroke, and any peripheral retinal disorder, including diabetic retinopathy.

1. BLURRED, HAZY VISION

Generalized blurring and haziness of vision is the rule in any abnormality of the optical media. Glare and photophobia may also be factors. Any corneal disease, cataracts, capsular opacification, or vitreous opacities interfere with refraction of light rays entering the eye. Such random refraction causes reduced acuity, glare, and decreased contrast. Pupillary miosis further restricts the quantity of light reaching the retina. Patients have difficulty seeing stairs and steps and other low-contrast objects. Acuity varies with ambient light.

Useful tests of visual function include Snellen visual acuity, glare test, and contrast sensitivity. A potential acuity meter (PAM) used in conjunction with a glare test helps to differentiate retinal from media pathology.

Management

Refraction should always be carefully done, including multiple pinholes, stenopeic slit, and keratometry. Modification of illumination and attention to details of room and task lighting are most important. Antireflective lens coatings and neutral gray lenses reduce light intensity (and therefore glare). Yellow and amber lenses enhance contrast. Ultraviolet filters should be used particularly for pseudophakic patients. Large bold print provides the higher contrast the patient needs.

Magnification may or may not be effective depending on the patient's level of contrast sensitivity. A magnified image itself has low contrast. The glare from an illuminated stand magnifier may actually reduce reading acuity. Large bold print may be a better choice than a magnifier-or a reading slit of matte black plastic to reduce glare and outline the text. Contact lenses, keratoplasty, laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) refractive surgery, posterior capsulotomy, and intraocular lens implants may also be considered in specific cases. The cataract surgeon may wish to discuss overcorrecting the power of the implant by a few diopters. The resulting myopia would allow the low-vision patient useful uncorrected vision in the intermediate range.

2. IMPAIRED RESOLUTION

Macular edema from a variety of disorders and congenital foveal aplasia of albinism affect only a few degrees of the fovea. As a rule, the acuity is in the higher range from 20/50 to 20/200.

Useful tests of visual function include Snellen visual acuity, Amsler grid, and contrast sensitivity.

Management

Careful refraction should be done to rule out astigmatic error. Patients usually accept reading adds of +4 to +10 D and are proficient readers. Bifocals or contact lenses should be considered for stable or congenital conditions. Albinos with nystagmus can wear toric contact lenses successfully.

3. CENTRAL SCOTOMAS

Central vision is essential for details, color vision, and daylight vision. The macula consists predominately of cones. The two commonest causes of macular disease are atrophic (dry) and exudative (wet) macular degeneration, both of which are more prevalent in today's aging society. Other causes are macular holes, myopic macular degeneration, optic nerve disease (cecocentral scotoma), and congenital macular disorders. Laser treatment near the fovea may result in a dense scotoma.

In the early stages of macular disease, patients most often report blurred or distorted central vision. Peripheral vision is unaffected unless there is a cataract to complicate the picture. The loss of central vision interferes with reading, seeing facial features, and other details. Dense scotomas are not present unless there is scarring following choroidal or subretinal hemorrhage (disciform disease). Contrast sensitivity decreases as the disease extends beyond the fovea. Macular degeneration generally does not hinder safe travel because the peripheral vision is effective for orientation purposes.

Tests of visual function include Snellen acuity, Amsler grid, and contrast sensitivity. Reduced contrast indicates the need for higher magnification, more contrast, and more illumination than predicted from the Snellen acuity.

Management

Patients often spontaneously adopt an eccentric head tilt or eye turn to move images from nonseeing retina to a viable parafoveal area. The ability to move the scotoma may be demonstrated to a patient during the Amsler grid test. Some patients respond to bilateral prisms in spectacles to relocate the image.

Magnifying lenses enlarge the retinal image beyond the scotoma. The power of the lens is related to the near acuity and contrast sensitivity, as well as location and density of the scotoma. Patients may use different types of devices for various tasks: spectacles for reading, hand magnifier for shopping, CCTV for writing and typing. Most people learn to use low-vision aids successfully, particularly after instruction sessions to reinforce correct usage. Older people may require more time and repetition. All patients need to be reassured about the remote possibility of blindness.

4. PERIPHERAL SCOTOMA

Scotomas in the peripheral field are characteristic of end stage glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa, diabetic retinopathy treated with photocoagulation, and central nervous system diseases and disorders such as tumor, stroke, or trauma. The peripheral field is essential for orienting oneself in space, detecting motion, and for awareness of potential hazards in the environment. The predominantly rod vision is most sensitive in twilight and at night. A person with a constricted field may be able to read small print yet need a cane or guide dog to get around.

Management

Adequate task and ambient lighting is essential for persons who depend for vision principally on the macula. Photophobia often results from using high levels of light, which may be relieved by introducing amber to yellow filters that block ultraviolet and visible blue light below 527 nm.

If a cataract seems to interfere with optimal function, a combination of contrast sensitivity and glare tests may indicate the best timing for cataract surgery. The posterior chamber implant should contain an ultraviolet blocking agent.

When the central field diameter is less than 7 degrees, magnification may not be advantageous to the patient. Telescopes and spectacle magnifiers may enlarge the image beyond the useful field. Hand magnifiers and closed-circuit television or computers may be the equipment of choice because the size of the image can be adjusted to match the size of the field.

*Legal blindness-defined as best corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye or a visual field of 20 degrees or less-affects 1,000,000 individuals in the USA (see Chapter 23).

Vistech Contrast Sensitivity Vision Test, Pelli-Robson, Lea Test System and Symbols available from The Lighthouse Low Vision Catalog, 111 East 59th Street, New York, NY 10022.

Vistech Contrast Sensitivity Vision Test, Pelli-Robson, Lea Test System and Symbols available from The Lighthouse Low Vision Catalog, 111 East 59th Street, New York, NY 10022.

List of Figures

| Figure 22-1: Lighthouse modification of the Ferris-Bailey ETDRS chart in a movable light box. | |

| Figure 22-2: Low-vision spectacle aid. Patient demonstrates close reading distance (with lenticular spectacle) but with both hands free to hold reading material. | |

| Figure 22-3: Hand magnifiers of varius types and strengths. | |

| Figure 22-4: A woman with macular degeneration uses a fixed-focus stand magnifier. Her hand tremor prevented her from using a hand magnifier. | |

| Figure 22-5: Low-vision telescopes. A: Hand-held monocular telescope. B: Spectacle-mounted Galilean focusable telescope. |

List of Tables

| Table 22-1: Common activities that are adverlsely affected by visual impairment are listed with suggestions for low vision aids. |

10.1036/1535-8860.ch22