BENIGN FIBRO-OSSEOUS AND CARTILAGINOUS LESIONS

Osteoma

A true osteoma is a tumor-like mass of bony tissue that is histologically similar to normal bone. Its pathogenesis remains unclear, although traumatic, infective, or hamartomatous theories have been proposed.4 Others have suggested that osteomas arise exclusively at the junction of bones of cartilaginous and membranous origin.5 None of these theories account for the facts.

The most common sites of origin are the paranasal sinuses, skull, and facial bone. The fact that osteomas were found in 0.42% (15 of 3510) of plain sinus radiographs reflects their prevalence.6 In the sinuses, 50% occur in the frontal sinus, with the ethmoid, maxillary, and sphenoid involved in descending order of frequency. Most orbital osteomas are secondary invaders from adjacent sinuses, but on occasion they arise primarily in the orbit. In contrast to the sinus distribution, however, orbital osteomas appear to have a roughly equal origin from the ethmoid, frontoethmoid, or frontal regions.7,8 This may reflect the relatively thin barrier to expansion posed by the medial orbital wall.

The age range runs the gamut from 10 to 82 years, with the highest prevalence in the fourth and fifth decades. Males and females are represented equally.7–9

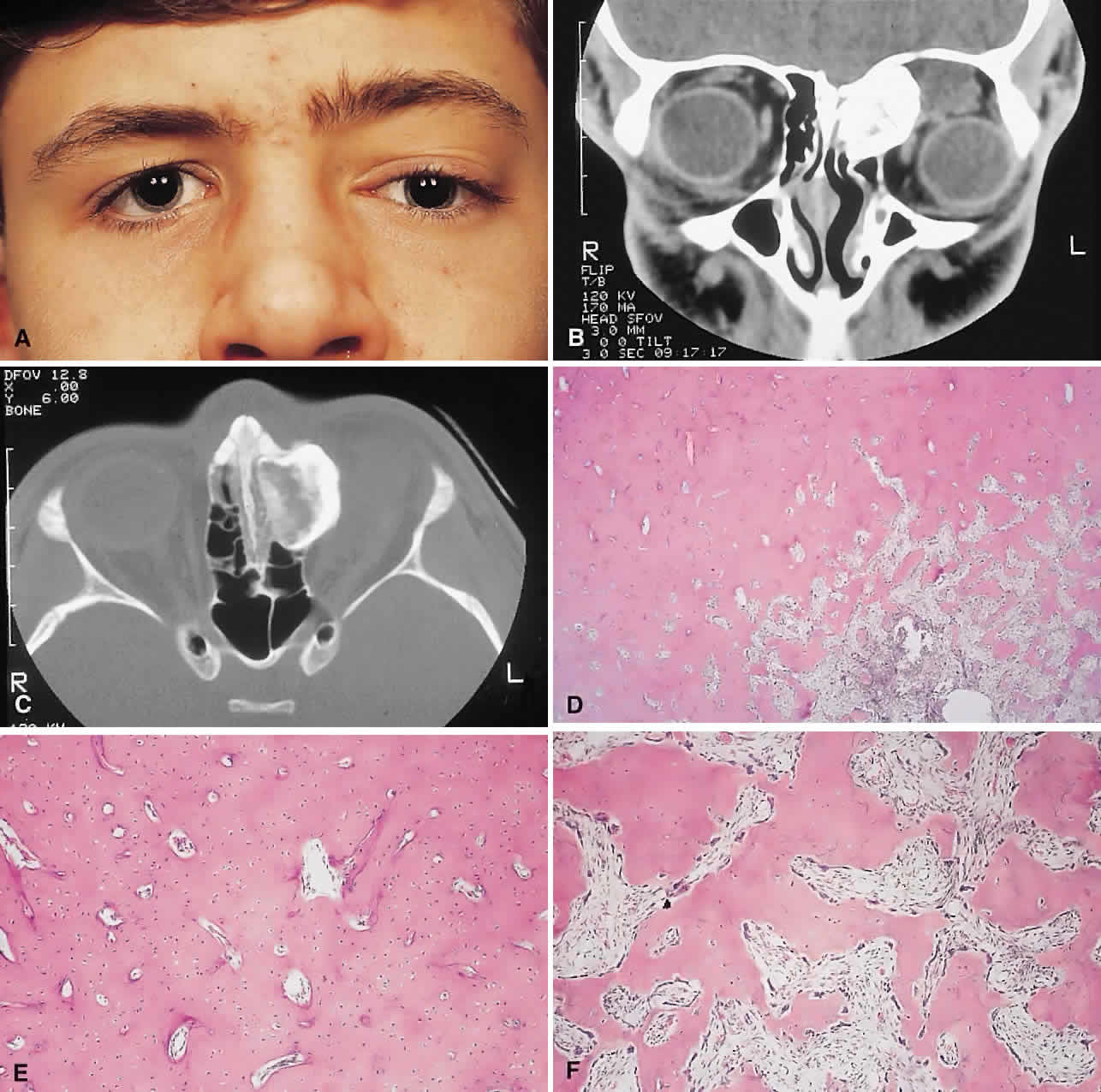

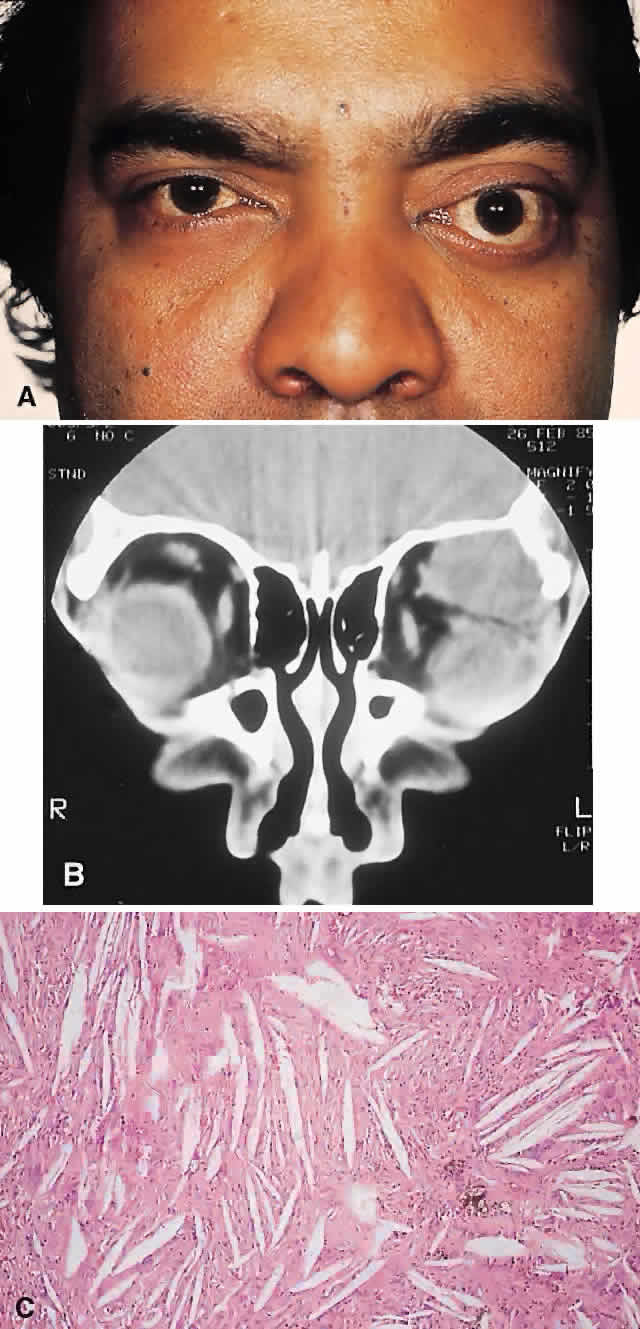

PRESENTATION. Most sinus osteomas are solitary and asymptomatic.6 However, when large enough to encroach on the orbits, a gradual evolution of proptosis or globe displacement over many years can occur (Fig. 1). There may be an associated headache as a result of expansion of the overlying cortex and periosteum, and a bony mass is often palpable in the superior or superomedial orbit. Obstruction of the sinus ostia may lead to chronic sinusitis or mucocele. Less common features include an acquired Brown syndrome,10 gaze-evoked amaurosis or pain,4,11 subluxation of the eye12 and erosion leading to orbital emphysema, or cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea.13 The sphenoid sinus, although a rare site, is significant because even a small lesion may lead to an orbital apex syndrome.

An uncommon but important systemic association is Gardner's syndrome. This autosomal dominant syndrome of osteomas, soft tissue tumors, and peripheral congenital retinal pigment epithelial hypertrophy also includes the development of colonic polyposis with subsequent malignant transformation.14–16 Multiple osteomas are common; our one patient had only a single tumor, but one was also noted in the skull. Further, because bony lesions may predate the colonic pathology, patients with osteoma warrant a dilated funduscopy and referral to a gastroenterologist.17

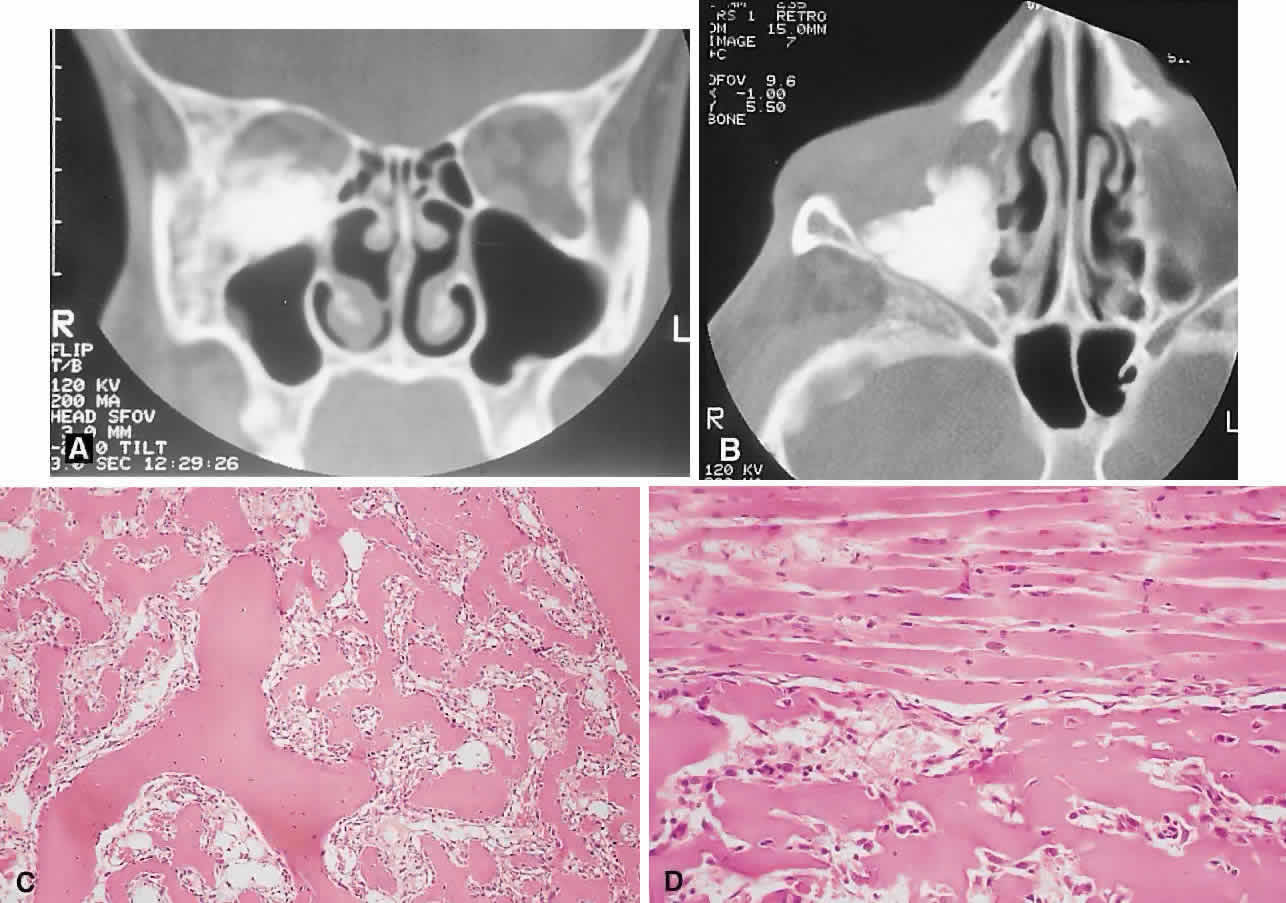

IMAGING. The plain radiograph and CT appearances consist of an osteoblastic round or ovoid sharply circumscribed mass, usually arising in the sinus and invading the orbit. Tumors growing in a sinus conform to its internal contour and often have a bosselated surface. Osteomas may be sessile or pedunculated and generally have a diameter of 1 to 5 cm.18 Bone window settings on CT imaging often show a very dense periphery with a more cancellous internal structure. However, the relative proportions of the two densities may vary with the size of the lesion.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. It is important to distinguish osteomas from reactive osteomatous responses to infection, trauma, and chronic inflammation. The clinical and radiologic appearances are often invaluable in this regard.

Macroscopically, true osteomas have smooth or bosselated contours with a glistening white or pinkish coloration. A covering of mucoperiosteum or periorbita may be seen, depending on the site of origin.18

Osteomas have been classified histologically into three groups depending on the predominant tissue present: compact (cortical, ivory), cancellous (trabecular, spongy), and fibrous. Fu and Perzin19 have postulated that the histologic type is partly dependent on the age of the lesion, with the compact group representing the most mature and the fibrous the least. The fibrous subtype may, in fact, be part of a continuum incorporating ossifying fibroma and fibrous dysplasia.

The compact areas resemble normal cortical bone with dense bony areas and haversian systems. However, there are subtle differences in the arrangement of the haversian canals, which is often evident to the experienced bone pathologist. The cancellous areas consist of anastomosing trabeculae with an intervening fibrovascular stroma. Fatty and hematopoietic elements may also be present in the stroma, as well as evidence of osteoblastic activity along the trabeculae. The fibrous region is made up primarily of loose fibrovascular tissue with a few irregular bony trabeculae and osteoid elements.

In our series of nine surgically treated cases, we noted that although the three types of tissue were present in varying admixtures, in all cases there was a remarkably consistent pattern of arrangement. The most peripheral zone was made up of compact bone; moving toward the center or base of the lesion, there was an intermediate zone of increased osteoblastic activity, osteoid, and vascularity. The innermost region consisted of a loose fibrous stroma with a greater number of blood vessels, few trabeculae, and many plump osteoblasts. This configuration has been described previously by Albert and associates20 and illustrates the growth of these lesions.

The outermost zone presumably represents more mature bone, and the activity seen centrally suggests that this is where growth is initiated. This implies that extirpation of the central region is probably required to prevent recurrence. It may also explain why leaving residual peripheral areas does not usually lead to regrowth.

Finally, the histologic subtyping into compact, cancellous, and fibrous lesions probably has little practical significance, because there appears to be no correlation with the clinical course.

MANAGEMENT. Generally, asymptomatic osteomas can be treated conservatively. The only possible exception to this is in the sphenoid sinus: it is technically easier to remove a small lesion in this location before it has encroached on the orbital apex and optic canal.

If symptomatic and located in the anterior orbit, osteomas can be removed through an anterior orbitotomy. For anterior ethmoid tumors in the superomedial orbit, a modified Lynch incision is often used. Excision can sometimes be aided by coring the lesion and collapsing the cortex for removal. For more posterior tumors, involving the roof or cribriform plate, a combined orbitocranial approach using a bicoronal incision is favored.21 Recurrence is rare, even after a partial resection.

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a benign disorder in which proliferation of fibrous tissue and osteoid replaces and distorts medullary bone. The cause is unknown; past theories have included a maturation arrest at the woven bone stage, or hamartomatous proliferation.22 More recently, the discovery of a postzygotic mutation in the G protein in McCune-Albright syndrome suggests that the bone dysplasia in these patients is a manifestation of a somatic mosaic state.23,24

There are three forms of fibrous dysplasia: monostotic fibrous dysplasia (MFD), polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (PFD), and McCune-Albright syndrome.22,25 MFD accounts for 75% to 80% of cases, of which 20% affect the craniofacial bones. In the skull, the frontal bone is most commonly involved, followed by the sphenoid and ethmoid. Most patients with orbital involvement have MFD, although the disease has generally spread to contiguous bones by the time the patient comes to medical attention. PFD makes up 20% of all cases; half of these patients have head and neck involvement. McCune-Albright syndrome occurs largely in females and incorporates the triad of PFD, sexual precocity, and cutaneous pigmentation.26 This pigmentation appears as brown macules, usually six or fewer, with irregular “coast of Maine” borders.27

Fibrous dysplasia is generally recognized before age 30, although mild or asymptomatic cases may escape detection into late adult life.28 The gender distribution is roughly equal in MFD; there is a female predilection in PFD.

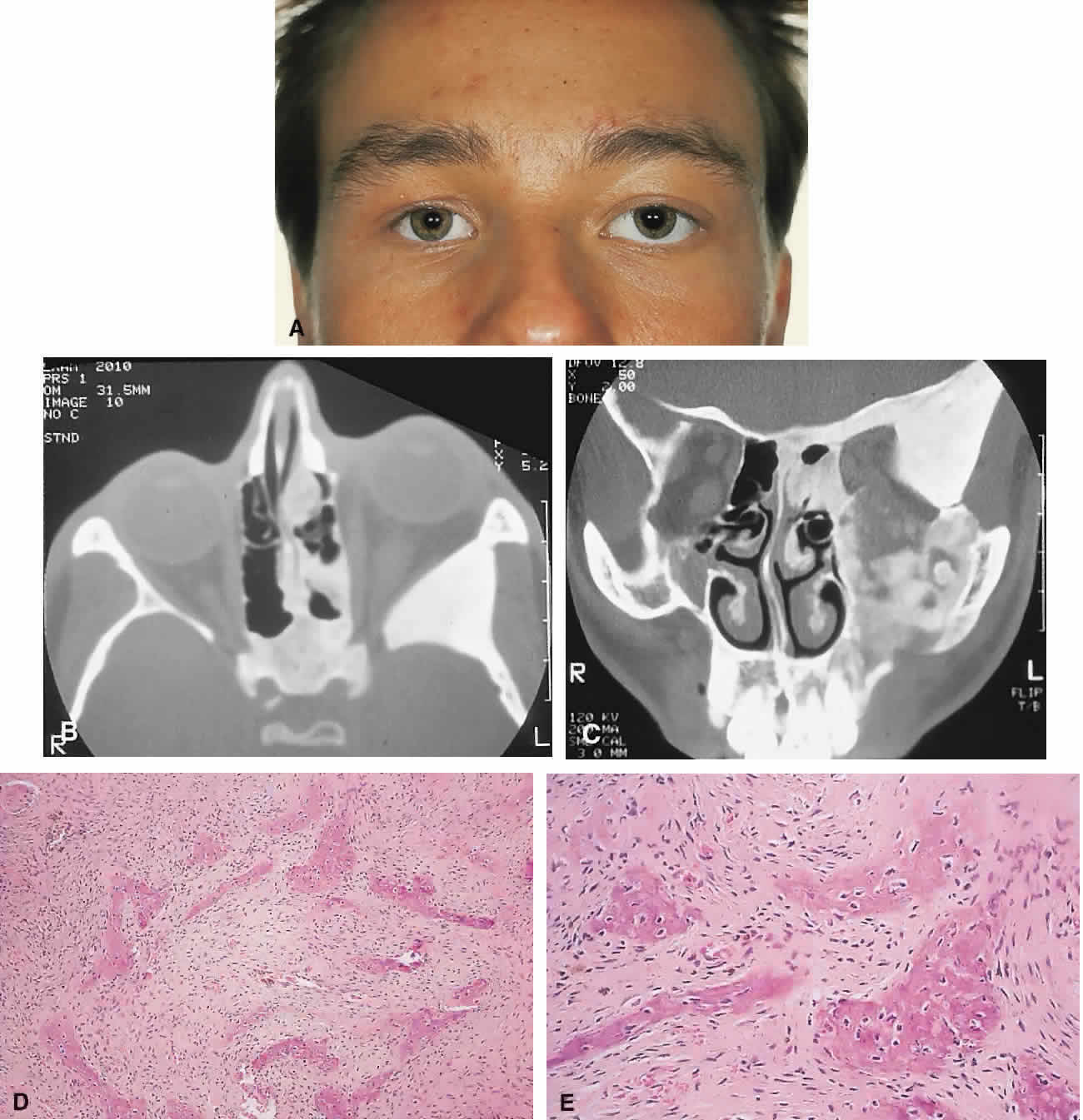

PRESENTATION. The site and the extent of disease are the major determinants of symptomatology. Facial asymmetry, proptosis, and globe displacement evolving over many years are the most common manifestations (Fig. 2). Nasolacrimal duct blockage, diplopia, nasal obstruction, malocclusion, raised intracranial pressure, and cranial nerve palsies also occur.25,28–30 Acute or subacute compressive optic neuropathy can arise as a result of intralesional hemorrhage, sphenoidal mucocele, or secondary aneurysmal bone cyst.31 A more chronic visual loss, although less commonly reported, may occur as a result of compression in the optic canal or at the chiasm. On occasion, a superimposed ischemic neuropathy in the context of chronic compression leads to an acute on chronic deterioration in vision.32

This clinical spectrum is reflected in our experience of 10 cases. Changes in facial contour (7 patients), proptosis (7), globe dystopia (6), and decreased vision (3) were the major signs. Interestingly, seven patients also had pain, either localized to the orbit or described as a diffuse ipsilateral headache.

Overall, the natural history is one of slow growth. Although this was previously thought to cease in adult life, there is evidence that fibrous dysplasia may progress well past the fourth decade.25

Rarely, malignant transformation to osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and giant cell sarcoma can occur; this is often signaled by a more rapid progression and increased pain. The incidence of this complication is estimated at 0.4% to 0.5%, rising to approximately 15% with prior radiation therapy.33

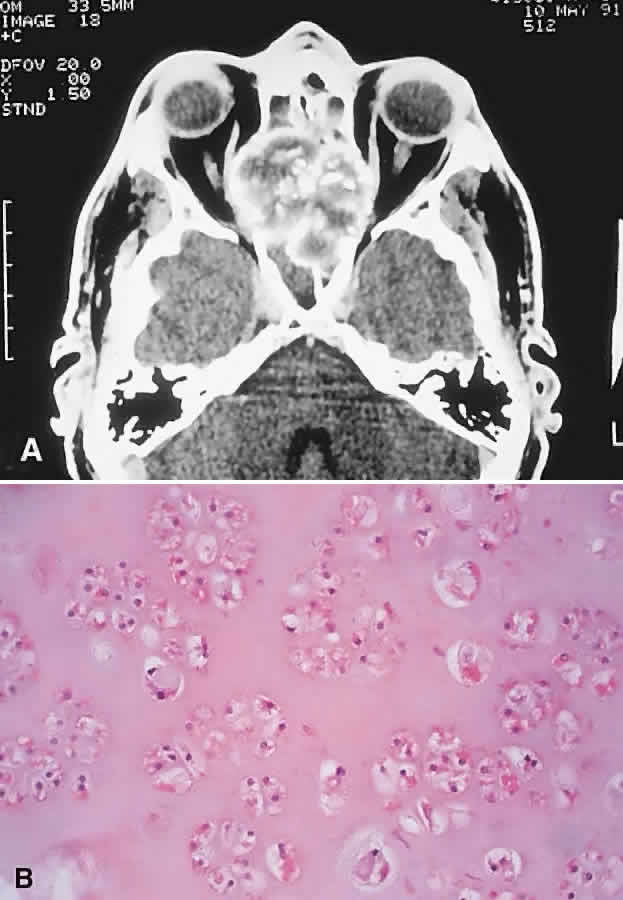

IMAGING. In the craniofacial bones, fibrous dysplasia tends to expand the bone, with thinning of the overlying cortex. The margins are poorly defined, and the dysplasia transgresses suture lines; the proportion of mineralized to fibrous tissue determines the degree of radiolucency. Most cases demonstrate a relatively equal mixture, resulting in a pagetoid appearance. Where the fibrous element is predominant, there may be cystlike areas; a preponderance of mineralized tissue, however, results in a homogeneous, sclerotic, “ground-glass” picture. Fries34 reviewed 39 patients with fibrous dysplasia of the craniofacial bones and found a pagetoid pattern to be most common (56%), followed by sclerotic (23%) and cystlike (21%) appearances.

The primary differential is hyperostotic meningioma. This is distinguished by its occurrence in an older age group and by the presence of an associated enhancing soft tissue component, best seen on MRI. Also, meningioma often causes a more homogeneous thickening of bone, which in contrast to fibrous dysplasia does not leave a discernible cortical rim. MRI shows meningioma to have a signal isointense to gray matter on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Fibrous dysplasia, in contrast, tends to have a lower intensity on T1- and a heterogeneous signal on T2-weighted images.28,35 MRI may also have a role in fibrous dysplasia in the evaluation of mucoceles and recent hemorrhage.

On occasion, Paget's disease and less commonly cystic bone lesions, such as localized Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma), also enter into the differential diagnosis. Paget's disease arises beyond the age of 40, is usually bilateral, and radiologically may show areas of cotton wooltype density that are not usually seen in fibrous dysplasia.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Macroscopically, fibrous dysplasia consists of gritty, white-to-pink tissue, often with blood or serous-filled cystic areas. Histologically, there is a fibrous background containing trabeculae of woven bone. The stroma has variable amounts of collagen, fibroblasts, and vascularity. There may also be myxomatous areas and secondary aneurysmal bone cysts. The curvilinear bone trabeculae take on a variety of configurations, including C or Y shapes (so-called Chinese characters). These trabeculae sometimes have irregular margins as a result of the attachment of collagen fibers arising in the stroma. Cartilaginous nodules as well as small foci of lamellar bone are occasionally seen, but the vast majority of lesions contain immature woven bone. At its periphery, fibrous dysplasia permeates normal bone, and there may be areas of reactive bone with more prominent lamellar bone formation and osteoblastic rimming. Sequential biopsies of fibrous dysplasia from childhood to adult life have shown that the histologic picture does not change with time.36

In the skull, the major histologic differential is ossifying fibroma. The latter, however, is a more circumscribed lesion that displays prominent production of lamellar bone with osteoblastic rimming.

MANAGEMENT. Traditionally, there has been a conservative approach to surgery for fibrous dysplasia, with intervention reserved for gross deformity, functional deficits, pain, or sarcomatous transformation. The procedures included resection if the lesion was well localized, curettage with bone grafting, or contouring. The last two decades have seen a shift to more aggressive and earlier intervention. A multidisciplinary craniofacial approach has been advocated, wherein as much affected bone as possible is removed and the resulting defects are reconstructed in a single operation.37 The indications for intervention include those previously mentioned, with the added rationale of attempting to prevent complications such as optic nerve compression.23,38 However, long-term follow-up data comparing outcomes with the natural history of the disease are lacking. Also, there have been two reports of blindness complicating prophylactic optic nerve decompression.25,32,39 Thus, the need for prophylactic treatment remains unresolved; it is not recommended unless a functional deficit develops.

Ossifying Fibroma

There is controversy as to whether ossifying fibroma is a distinct clinicopathologic entity: some authors believe it is a variant of fibrous dysplasia.40 Nevertheless, there appear to be enough disparate features to characterize it as a benign fibro-osseous neoplasm.

Ossifying fibroma occurs most commonly in the mandible in the first two decades of life, with a proclivity for females. Only rarely does it arise in the orbit, with the frontal bone being most commonly involved, followed by the ethmoid and the maxillary bones. There are 37 orbital cases reported in the literature, with an age range of 4 months to 52 years and an approximately equal male/female ratio.12,19,41–50

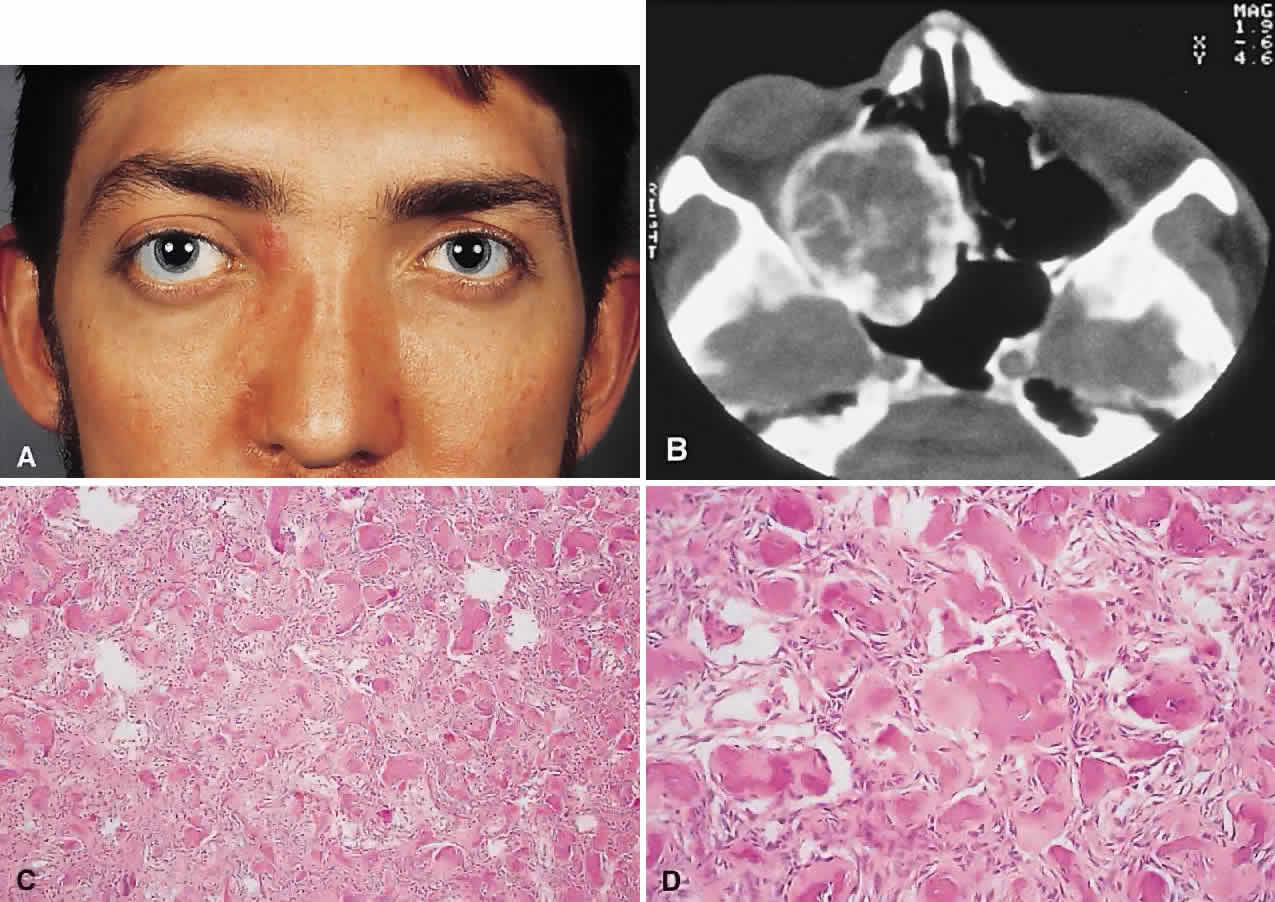

PRESENTATION. As a result of its slow growth, ossifying fibroma generally manifests as a gradual painless globe displacement, with a temporal course measured in years. The mass effect may also lead to proptosis, diplopia, and, if situated more posteriorly, compression of apical structures.

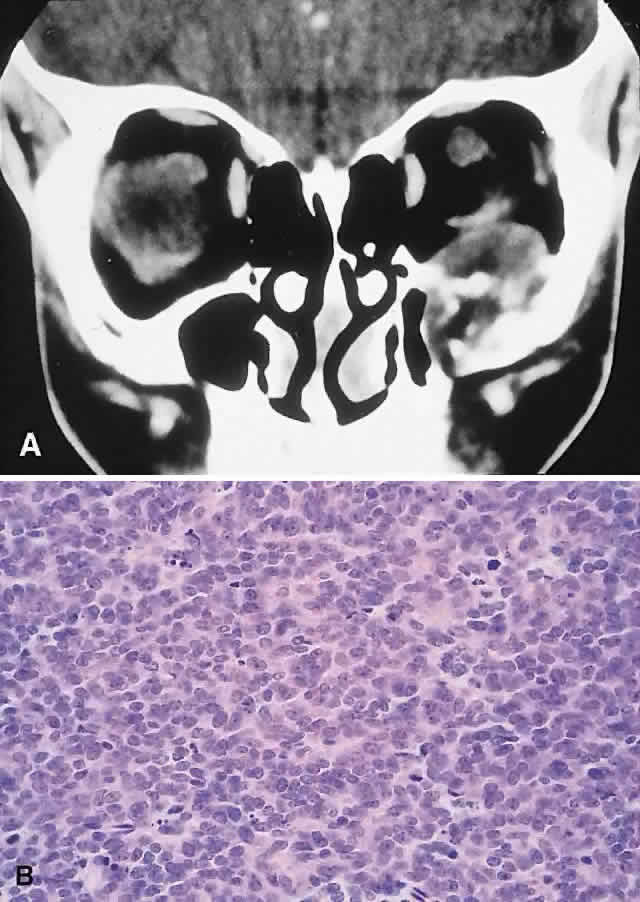

IMAGING. Ossifying fibroma starts as a monostotic lesion that expands the bone of origin in a well-circumscribed manner. However, with growth it may spread to involve adjacent bones and may even extend across the midline to involve both orbits. The characteristic CT appearance is of a round or ovoid mass with a well-defined, thin sclerotic margin (Fig. 3). Centrally, there is often a patchy pattern of osteoblastic and osteolytic areas.46

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Macroscopically, the lesional tissue is white to red and has a largely soft fibrous texture with variable grittiness, dependent on the amount of osteoid. Microscopically, it consists of a cellular vascular stroma containing trabeculae of lamellar bone. These bony trabeculae often have a thin surrounding of osteoid and, in contrast to fibrous dysplasia, display prominent osteoblastic rimming. There may also be osteoblasts as well as a few foci of giant cells in the stroma. If larger specimens are available, they may demonstrate a zonation phenomenon, seen as an increasing maturity of bone toward the periphery.19

In the psammomatoid variant described by Margo and colleagues,49 at least half of the tumor contains sphericular ossicles. This histologic pattern has been correlated with a more aggressive local behavior and a tendency to recur after incomplete excision.

MANAGEMENT. The natural history of ossifying fibroma is one of inexorable progression; thus, surgical intervention is generally required. Because the propensity for recurrence after incomplete excision is well recognized, the surgical objective should be complete removal. This is particularly applicable in the psammomatoid variant. For anterior, relatively small lesions, this may be achieved using a percutaneous or bicoronal approach. However, most tumors tend to be sizable (5 cm in diameter) at presentation.49 Thus, for these lesions as well as those located more posteriorly, combined orbital, neurosurgical, and rhinologic approaches are usually necessary.45

Osteoblastoma

Osteoblastoma is a benign tumor composed of osteoblasts that produce osteoid and bone. It usually arises in the vertebrae and long bones, and its occurrence in the craniofacial region is extremely rare. These tumors are most commonly seen in the second and third decades and have a male/female ratio of 2:1.51

Seven cases with orbital involvement have been reported in the past 30 years.19,52–57 In four of these, the tumors appeared to arise from the orbital roof, with the remainder originating in the ethmoid sinuses. The natural history is of slow growth, although a minority display a more aggressive behavior (aggressive osteoblastoma).

PRESENTATION. The presentation in all patients was of a slowly progressive mass effect with proptosis and either downward or outward displacement of the globe. Pain or discomfort was a feature in several patients.

IMAGING. In the long bones, osteoblastomas produce cortical expansion and have a lytic center. They can also simulate a large osteoid osteoma, with a lucent halo and central ossification. The different morphology of the orbital bones means that the tumor appears as an osteolytic lesion with a sclerotic margin; it occasionally has ossification of the matrix.51

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The gross appearance is of a relatively gritty or friable, reddish-brown tissue. There is a broad spectrum of histologic appearances. The typical picture is of a network of osteoid trabeculae with osteoblastic rimming. These osteoblasts generally have abundant cytoplasm and regular nuclei. However, in some tumors, large epithelioid osteoblasts or a pseudosarcomatous appearance can be observed; this can lead to confusion with osteosarcoma.58 In contrast to osteosarcomas, however, even atypical osteoblastomas show a tendency toward peripheral maturation and do not permeate surrounding bone. Some authors have suggested that this atypical appearance may correlate with a more aggressive clinical course and have used the term aggressive osteoblastoma to define a separate clinicopathologic entity. It is a rare variant, with only one case being reported in the skull.59

The histology of osteoblastoma is similar to that of osteoid osteoma, with the latter being distinguished by a size smaller than 1.5 cm as well as a somewhat less cellular and vascular stroma.60 Nevertheless, they may represent a spectrum of disease, a fact somewhat supported by the recent finding of a common clonal chromosomal abnormality in both tumors.61 Osteoid osteoma, however, has not been reported in the orbit.

MANAGEMENT. Excision is generally curative; however, there is one report of recurrence of an orbital tumor after a piecemeal removal.56 There have also been descriptions of a benign osteoblastoma of the skull that developed into an osteosarcoma after an incomplete excision,62 as well as a case of aggressive osteoblastoma of the temporal bone.63 In view of this, osteoblastomas should be completely removed under direct vision, where possible, to determine the margins. This usually entails an orbitocranial approach for tumors of the roof and a combined orbitorhinologic approach to those arising in the sinuses.

Chondroma

These benign cartilaginous tumors usually occur as asymptomatic lesions in the sinuses and nasal cavity. They rarely occur in the orbit, where they present as slow-growing, painless, firm lumps, often near the orbital rim or the trochlea.64,65 They have on occasion also been described in the soft tissues of the orbit.66 Radiologically, they are seen as well-circumscribed, dense masses that histologically consist of lobulated mature hyaline cartilage. Mature chondrocytes are seen in the cartilage, along with a variable fibrous or myxoid stroma. Surgical excision is always curative.64,67

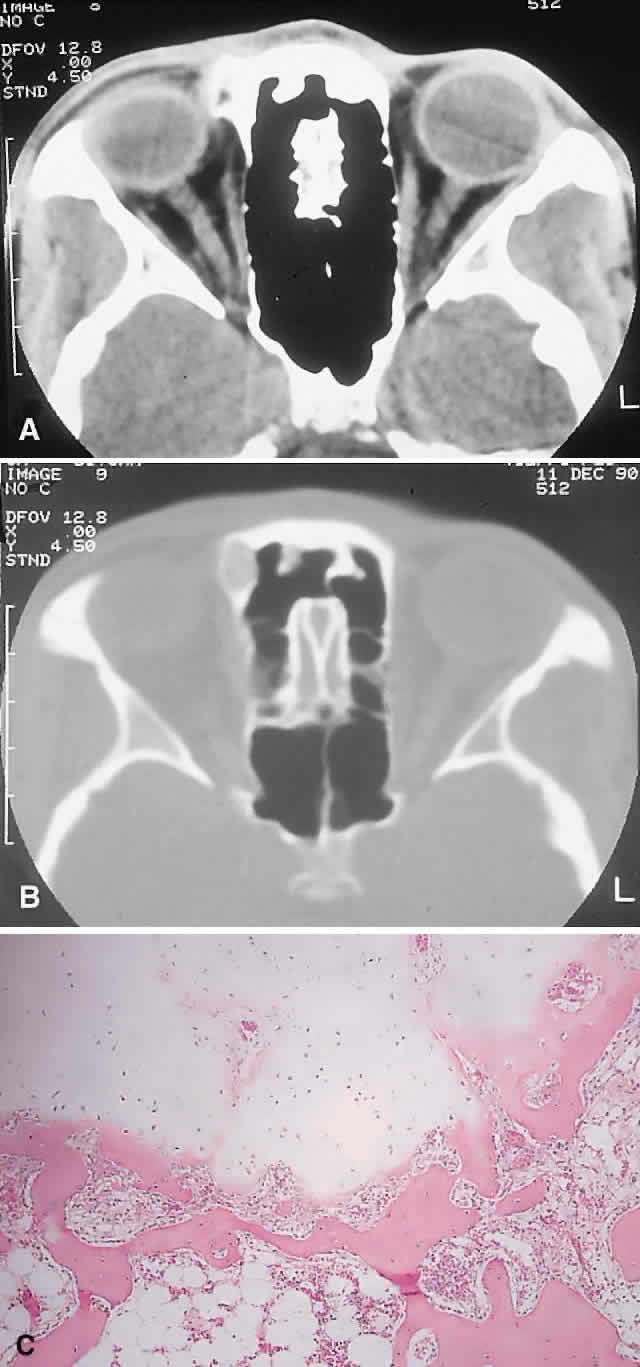

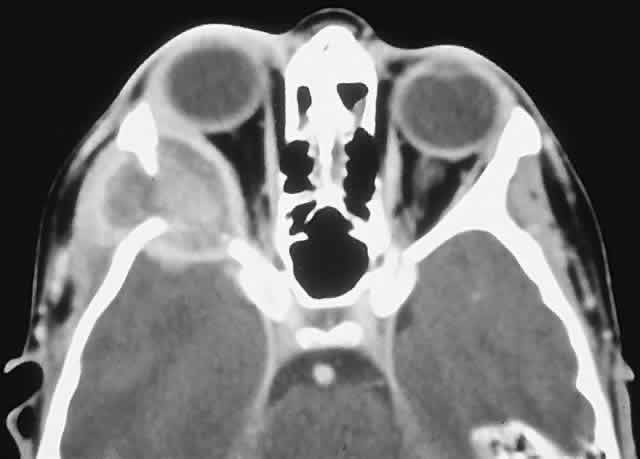

A variety of other benign cartilaginous tumors, including osteochondromas, enchondromas (Fig. 4), and fibrochondromas, have also rarely been described in the orbit, although the histologic documentation is not always convincing.68

REACTIVE LESIONS

Cholesterol Granuloma

A cholesterol granuloma is a foreign body response to the presence of crystallized cholesterol. The common sites are the middle ear and pneumatized portions of the temporal bone.69 In the orbit, it occurs almost exclusively in the diploë of the frontal bone overlying the lacrimal fossa, although it has also been reported in the zygoma.70

Theories of pathogenesis include a purely traumatic intradiploic hematoma or a hemorrhage occurring in a pre-existing bony anomaly. A breakdown of blood products then leads to cholesterol deposition and a granulomatous response. An analysis of 75 reported cases of orbital cholesterol granulomas revealed a marked preponderance of men in the fourth and fifth decades of life.70,71

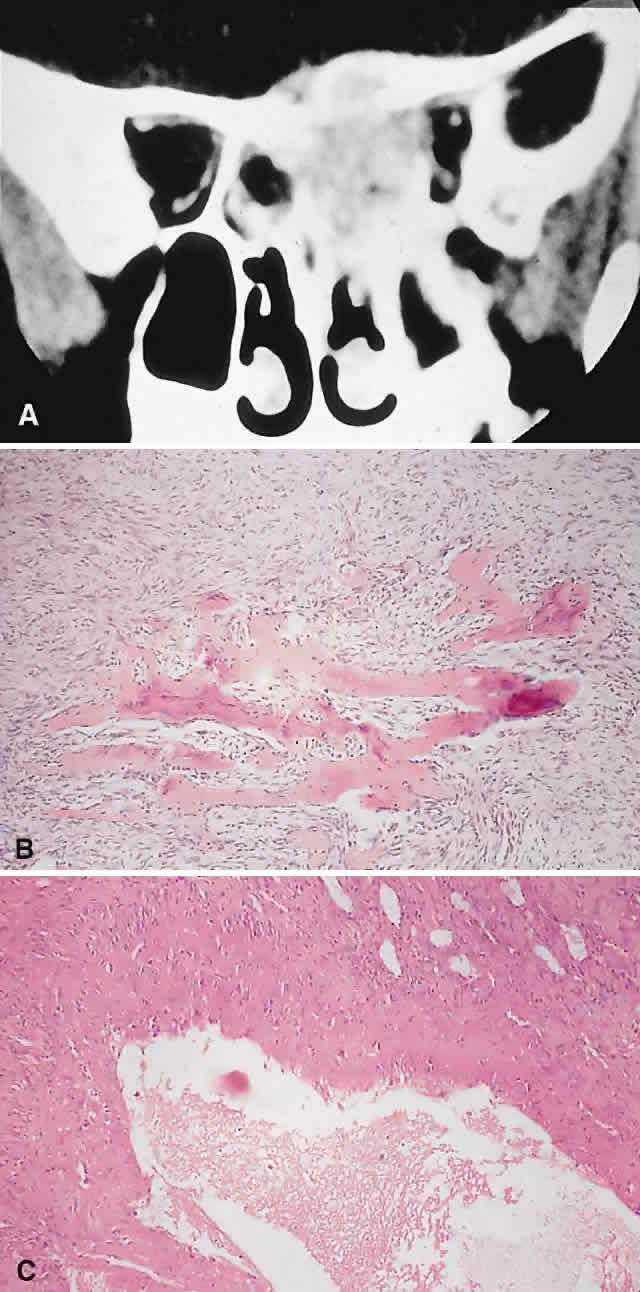

PRESENTATION. A superolateral mass effect encompassing weeks to years is the typical mode of presentation. This leads to inferior globe displacement, proptosis, and diplopia in upgaze (Fig. 5). There may be associated headache or pain; one third of patients recall a prior trauma.70,71

IMAGING. The granuloma arises in the diploë of the frontal bone, causing expansion and eventually erosion of the inner and outer tables. CT reveals it to be osteolytic, with a density equivalent to brain, and occasional intralesional bone fragments.72 Mature lesions display high T1 and T2 signal intensities on MRI.73,74 The most commonly evoked differentials in this setting are dermoid cysts and lacrimal gland carcinomas.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. These cysts usually contain yellow-brown viscous material with friable tissue and porous bone at the periphery. Histologically, the principal feature is the dominance of cholesterol clefts surrounded by granulomatous inflammation with conspicuous foreign body giant cells. A variable fibrous stroma is present and usually contains extensive blood-derived debris in the form of extracellular and intracellular hemosiderin as well as more recent hemorrhage.70,75

There should be no evidence of epithelial elements, ruling out a diagnosis of epidermoid or dermoid cyst. The prominence of the xanthomatous components also serves to differentiate this condition from giant cell granuloma and aneurysmal bone cyst.

We have seen six cases of cholesterol granuloma, two of which had histologic evidence of dysplastic-looking bone at their peripheries. This perhaps lends some support to the theory of a pre-existing dysplastic bony abnormality.

MANAGEMENT. A percutaneous approach and curettage is almost always curative, with only one well-documented case of recurrence that occurred when peripheral bone containing lesional tissue was not removed.71 If there is an extensive intracranial component, a combined orbitocranial operation may be required.76

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

This benign cystic lesion occurs most commonly in the metaphyses of long bones and in the spine. The pathogenesis is not known, although 30% to 50% occur secondary to other bone diseases, including fibrous dysplasia, giant cell granuloma, giant cell tumor, osteoblastoma, osteosarcoma, and intraosseous hemangioma.18,77,78 There is also evidence that some aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs) may arise as a reactive change to a pre-existing arteriovenous malformation.40 ABCs occur rarely in the skull; of those with orbital involvement, the frontal bone appears to be the most common location. An analysis of 24 recorded orbital cases, including 2 from our series, revealed an age range of 11 months to 42 years. Most presented in the second decade, and there was a female preponderance of 5:3.8,78–89

PRESENTATION. The usual signs and symptoms include proptosis, displacement of the eye, and diplopia. Masses in the midline can cause optic nerve compression.82 Because most ABCs arise in the orbital roof, intracranial extension can rarely give rise to raised intracranial pressure. Although typically subacute or chronic in evolution, sudden progression may occur as a result of intralesional hemorrhage.83

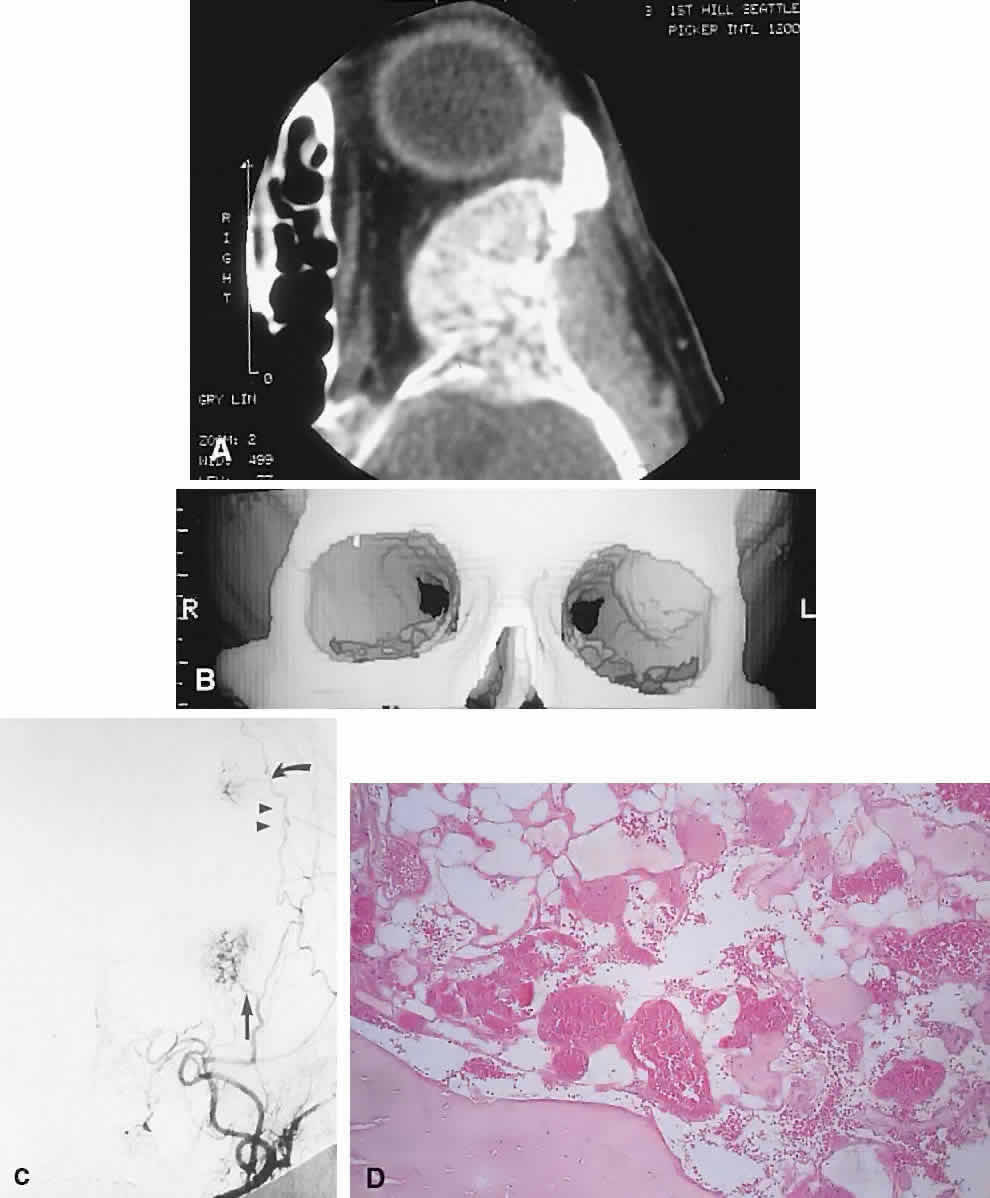

IMAGING. ABCs occurring in long bones have a characteristic uni- or multilocular expansile appearance. However, the radiology in the orbital bones is not specific and consists of destruction or expansion (Fig. 6). If expansile, the mass may have a thin cortical margin, but this is often absent as a consequence of erosion through to periorbita or dura. The central area is inhomogeneous, shows patchy enhancement, and can have multiple fluid levels, particularly in the more mature lesions.85,88 MRI may demonstrate recent hemorrhage in cases with an acute onset.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The gross specimen almost always consists of curettings of reddish-brown tissue with a texture that varies from friable to fibrous or gritty. More solid lesions may yield softer, pink to gray-white tissue. If larger samples are available, one may see honeycombed areas of serosanguineous or blood-filled cavitation.18,40 The cardinal microscopic features are cavernous blood-filled spaces that lack endothelial lining, pericytes, or smooth muscle. These spaces are bounded by a fibrous stroma that contains giant cells, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, lymphocytes, and trabeculae of osteoid and bone. The osteoid may lack osteoblastic rimming and may seem to arise from the stroma in a metaplastic fashion. Degenerating chondromyxoid areas may surround the osteoid and can display partial calcification.18,40

In 1983, Sanerkin and coworkers90 described a solid variant of ABC in which the aneurysmal sinusoids were either seen only in small foci or were absent. We have seen two cases that fit this histologic description. It is evident that this picture, apart from the chondromyxoid and sinusoidal foci, may bear a close resemblance to giant cell granuloma.

Finally, in any case of ABC, one should conduct a meticulous search for a primary pathology such as fibrous dysplasia.

MANAGEMENT. Curettage is typically curative. In the absence of an underlying bony abnormality, recurrence of orbital lesions is rare and usually occurs in the first 6 months.77,85 In such cases, a repeat curettage is generally successful. Resolution has also been reported after incomplete excisions. Radiation therapy has been used for recurrent aggressive lesions, but it entails a small yet definite risk of postradiation sarcoma.77

Giant Cell Granuloma

Giant cell granuloma (GCG) is a benign granulomatous proliferation of unknown cause. It has also been called giant cell reparative granuloma, the term referring to a past theory postulating a reparative process in response to trauma and hemorrhage.91 GCG occurs most commonly in the mandible, maxilla, and phalanges.92 Cases with orbital involvement have been reported rarely and appear to have arisen in the maxilla, frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones with equal frequency. Nine patients are reported in the literature and with the inclusion of our patient, they range in age from 5 to 54 years (average 18.6 years), and the male/female ratio is 3:2.93–98 This corresponds with the epidemiology of GCG elsewhere in the skeleton, which generally presents in the first two decades of life with an equal male/female ratio.94,96

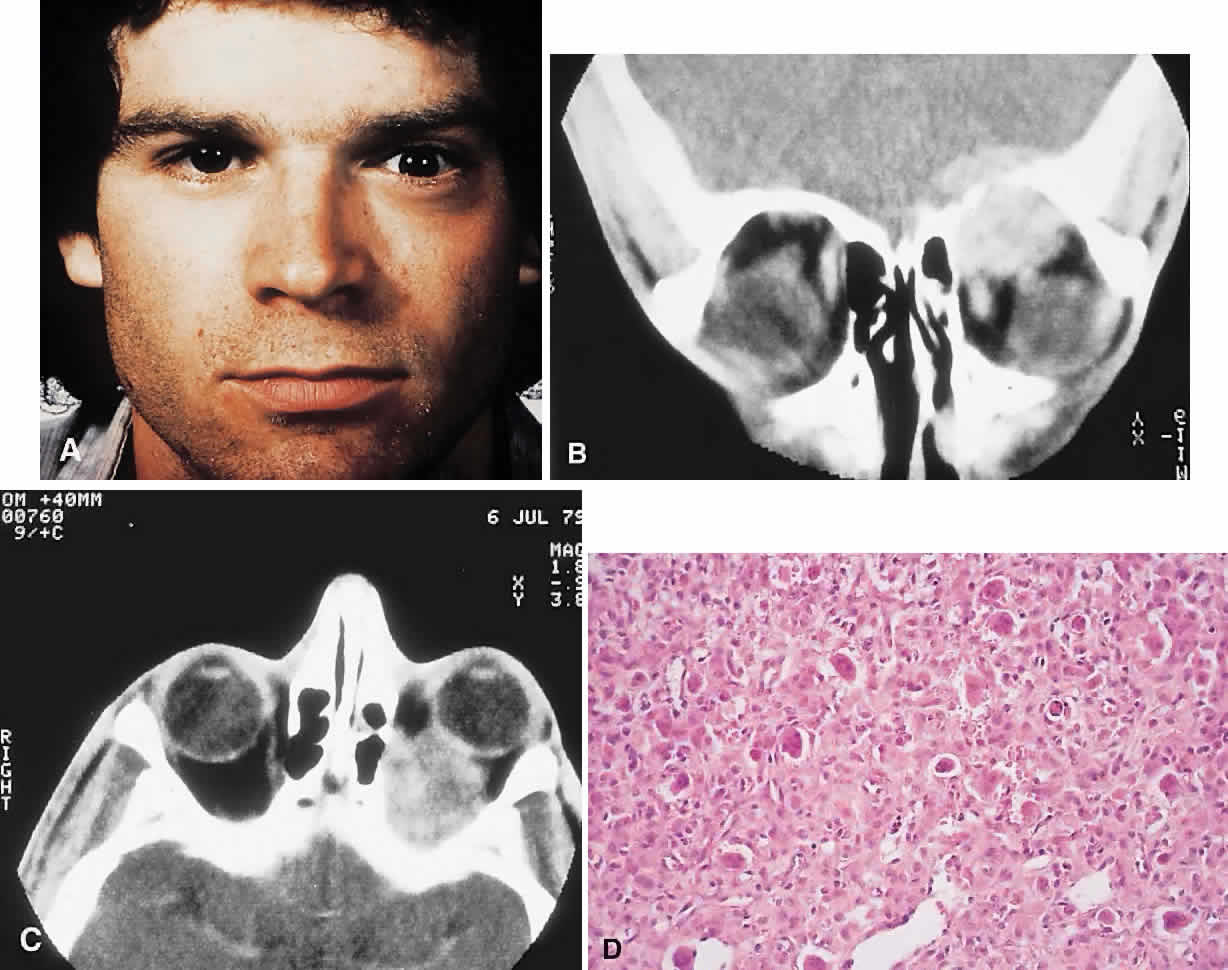

PRESENTATION. Proptosis and ocular displacement are the most common presentations, although headache and pain may be prominent (Fig. 7). Diplopia and decreased vision also occur, depending on the site of the mass. The time course is variable, ranging from months to years, and may be complicated by a rapid progression of symptoms resulting from hemorrhage.

IMAGING. GCG typically manifests as a destructive lesion with erosion of adjacent bone. It may have indistinct or sclerotic margins and may show moderate enhancement of an often-inhomogeneous central matrix.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Macroscopically, the granuloma consists of soft, friable, tan to brown tissue, typically in the form of curettings. A fibrous stroma with giant cells clustered around foci of hemorrhage is the dominant histology. This stroma contains ovoid and spindle-shaped fibroblasts with a variable amount of fibrosis and evidence of old and new hemorrhage. Reactive bone formation is common (75%) and consists of trabeculae of woven and lamellar bone, which may or may not demonstrate osteoblastic rimming. Areas of secondary aneurysmal bone cyst formation may also be seen.91,92,95

When the preceding histologic pattern is seen, investigations to exclude Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism are necessary. Once the latter diagnosis is ruled out, the histologic differential includes giant cell tumor and the solid areas in an ABC. It is important to differentiate giant cell tumor from GCG because the former is more aggressive and can undergo malignant transformation. Hirsch and Katz92 have outlined the histologic criteria for this differentiation. The major differences are that in giant cell tumor, the stroma is made up of largely plump, round, oval cells, and it displays less fibrosis than the often spindle-cell stroma of GCG. Also, the giant cells in giant cell tumor tend to be larger with more nuclei (more than 20) and are more diffusely distributed, rather than being centered around hemorrhagic foci, as in GCG. In addition, reactive bone formation is not a conspicuous feature of giant cell tumor. Nevertheless, the distinction between the two entities is not always sharply delineated.

MANAGEMENT. GCG generally responds well to curettage with or without bone grafting. A variable recurrence rate is reported for lesions elsewhere in the body, but most appear to be cured with a second curettage. This generalization appears to hold true for most orbital cases. However, in one patient described by Sood and colleagues,93 the tumor behaved in a locally aggressive fashion, requiring three operations and ultimately radiation therapy.

“Brown Tumor” of Hyperparathyroidism

“Brown tumor” represents a benign reactive proliferation with a histologic appearance virtually identical to GCG. Its association with primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, however, differentiates the former.

Brown tumors arise as a consequence of the increased osteoclastic activity associated with hyperparathyroidism. This leads to focal areas of bone resorption and hemorrhage. Histologically proven orbital Brown tumors have been described in 14 cases in the literature.8,12,99–108 They appeared in an older age group (range, 10 to 70 years; average 33 years), with a more marked female preponderance (5:2) when compared with GCG. Eight cases were associated with primary hyperparathyroidism and six with hyperparathyroidism secondary to renal dysfunction. The maxilla and the frontal bone were the favored sites, in that order.

Brown tumors tend to have a temporal onset usually measured in months and like GCGs are vulnerable to intralesional hemorrhage. Patients with Brown tumors also demonstrate abnormalities in serum calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, and parathormone levels and skeletal surveys.108

The radiologic and histologic appearances are essentially the same as for GCG (Fig. 8). Treatment of the hyperparathyroidism often results in spontaneous resorption and healing of the bony lesion.12,105,108 Hence, a careful clinical evaluation for manifestations of hypercalcemia or renal dysfunction may obviate the need for surgery.

NEOPLASMS

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) is the most common primary neoplasm of bone. Long bones are the most common site; orbital involvement is rare and usually from a maxillary focus. In most cases, the tumor arises de novo, but some are secondary to Paget's disease, fibrous dysplasia, radiation therapy, giant cell tumor, or osteoblastoma.40 Osteosarcomas are also seen as a second tumor in patients with familial retinoblastoma, even in the absence of radiation therapy. Also, a proportion of de novo osteosarcomas have been found to share the deletion of chromosome 13, which renders the retinoblastoma antioncogene inactive.109–112

De novo tumors are most common in the second decade, with a slight male predilection; however, osteosarcomas involving the orbit afflict an older population, being most common in the fourth and fifth decades (range, 10 to 54 years). The common precursor lesions for secondary tumors in the orbit appear to be radiation therapy, Paget's disease, and fibrous dysplasia.12,113–115

PRESENTATION. The course is typically more rapid than that of the benign tumors discussed previously, averaging approximately 4 to 6 months. In addition to any mass effect, there may be significant pain and infiltration leading to diplopia and decreased vision.

IMAGING. A mixed lytic and sclerotic mass with indistinct margins is the usual CT appearance (Fig. 9). Soft tissue infiltration of the orbit may also be evident, and the mass may contain foci of mineralization, producing fluffy densities. MRI can be of value in delineating the extent of any soft tissue component.12,116,117

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Gross specimens contain infiltrative tumor, which may be white, tan, or hemorrhagic in parts, with a soft to firm or gritty texture, depending on the stromal components. The stroma contains sarcomatous cells and must show at least some foci of osteoid production. The anaplastic cells may subsume a variety of histologic subtypes, including osteoblastic, chondroblastic, and fibroblastic. In most high-grade lesions, the cells are markedly malignant, but they become less so when incorporated into the osteoid (so-called normalization of malignant osteoid). The osteoid itself may assume a characteristic delicate filigreed or lacelike pattern.40

MANAGEMENT. The regimen for osteosarcoma involves preoperative chemotherapy, resection, and then continuation of the chemotherapy, with modifications based on the pathology of the resected specimen. Radiation therapy has an adjunctive postoperative role for residual tumor. These therapies have improved the 5-year survival rate from 20% to 70% for resectable lesions.118 However, the prognosis in the skull is poorer because of delayed diagnosis and inability to obtain complete resection once the tumor has gained access to the skull base or intracranial space.116,117

Chondrosarcoma

This malignant tumor is characterized by chondroid production and occurs most commonly in the lower extremities and pelvis. Orbital involvement is generally secondary to tumors arising in the sinuses and nasal cavity. Craniofacial chondrosarcomas have a male/female ratio of 2:1 and are prevalent in the fifth and sixth decades, with a wide age range.20,65,119–122

PRESENTATION. Because of their frequent sinus origin, chondrosarcomas usually manifest symptoms of nasal and sinus obstruction.65,123,124 Orbital mass effects often occur medially or inferiorly and consist of proptosis, ocular displacement, and epiphora secondary to nasolacrimal duct obstruction. There may be a variable degree of pain or headache as well as infiltrative features. Posterior growth leads to compromise of the optic nerve and apical structures. The course is usually prolonged, and symptom duration averages 2 to 3 years.

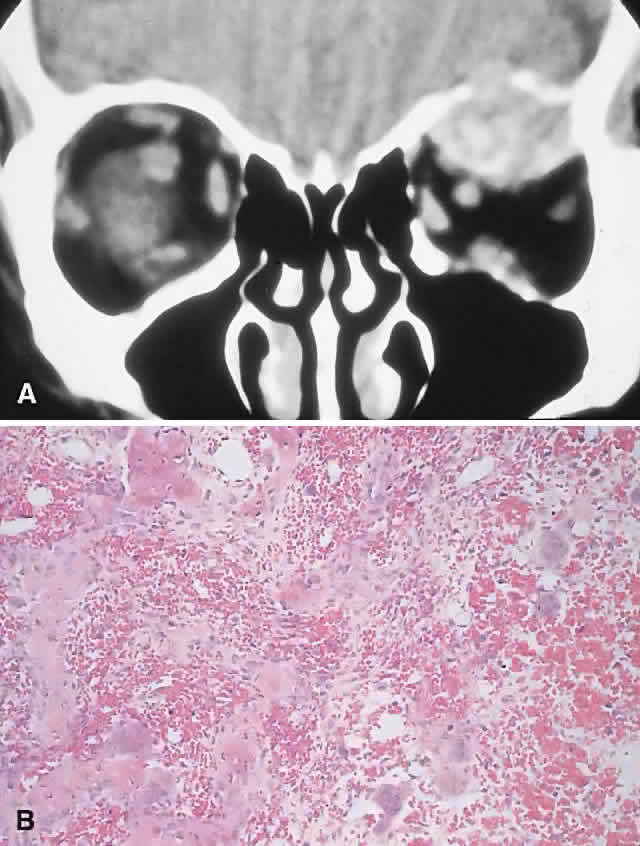

IMAGING. Chondrosarcomas appear as well-defined osteolytic lesions with stippled or mottled densities indicative of mineralization (Fig. 10). Higher-grade tumors tend to have irregular margins with nonuniform calcification in the form of amorphous cloudlike densities.125 The noncalcified regions show T1 signal intensities lower than or equal to gray matter on MRI. T2 signals are isointense to the cortex, and the masses usually display moderate enhancement.121,124,126,127

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Grossly, the tissue is white to blue-gray, with a discernible lobular pattern. Histologically, there are irregular lobules of hypercellular cartilage with lacunae containing plump bi- or multinucleated chondrocytes, separated by fibrous stroma or reactive bony trabeculae. The stroma may be myxoid in areas and shows a wide variability in the amount of cellularity, atypia, and chondroid matrix, which has led to a grading system. The grades 1 through 3 appear to have some correlation with prognosis.119,121,128 This is manifest in tumors involving the orbit, which are mostly grades 1 or 2 and exhibit slow growth with a low incidence of metastasis.

The major histologic differentials for conventional chondrosarcomas in the orbit are chondromas and chondroblastic osteosarcomas.

MANAGEMENT. Ablative surgery is the goal for resectable chondrosarcomas. However, for craniofacial tumors, this is often not possible, and because of their indolent growth a protracted course with multiple recurrences is common. Although not particularly radio- or chemosensitive tumors, both these modalities have been used in an adjunctive role for incompletely excised lesions.121,124 We have treated two cases of extensive grade 2 chondrosarcoma with radical debulking and postoperative radiation therapy. Both patients have no evidence of recurrence after 14 and 11 years, respectively.

Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is a variant of chondrosarcoma that commonly arises in the jaw. In the orbit, it favors the soft tissues, although bony involvement can occur. It occurs in a younger age group and in the orbit has a female predilection.122

In contrast to conventional chondrosarcoma, this tumor progresses more rapidly and presents with proptosis and infiltrative effects of less than a year's duration. Radiologically it appears on CT as a nonspecific, irregular, mottled, soft tissue mass; the MRI characteristics are similar to the noncalcified areas of the conventional type.127 Histologically, the mesenchymal variant consists of lobules of cartilage arising in a highly cellular stroma of malignant, small round cells. The chondroid production serves to differentiate it from other small round cell tumors, such as Ewing's sarcoma.

Because of its origin in the soft tissues, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is typically treated with exenteration. Despite the small number of reported orbital cases, it appears that resection is adequate therapy in certain patients. More recent reports suggest that mesenchymal chondrosarcoma may also be successfully managed by local resection with adjuvant chemo- and radiotherapy, thus obviating the need for exenteration.129 Compared with the conventional type, however, it has a more rapid course and a propensity for early spread, particularly to the lungs.

Ewing's Sarcoma

Ewing's sarcoma is a small round cell tumor that usually arises in bone. The characteristic chromosomal translocations (t(11;22)(q24:q12)) and proto-oncogenes expressed in this neoplasm suggest an undifferentiated neuroectodermal tumor.130,131 Most cases arise in the first two decades, with a predilection for males (1.5:1). The tumor is uncommon among blacks. Incidence in the head and neck is approximately 4% and favors the mandible and maxilla.18,132 Most orbital cases represent metastases or direct extension, with only a handful of primary orbital lesions reported.133–135 Hence, an orbital presentation should institute a rigorous search for a primary.

PRESENTATION. Nonaxial proptosis of relatively short duration is the usual presentation. We have encountered two cases of primary orbital Ewing's sarcoma, in patients 6 and 10 years old, respectively. Both boys had a 4-week history of ocular displacement. One tumor arose from the maxilla, the other from the nasopharynx.

IMAGING. The CT appearance is of an expansile or permeating mass that shows mottled bone destruction (Fig. 11). There may be an associated soft tissue component.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The tumor consists of firm, white tissue made up microscopically of sheets and clusters of uniform, small round cells. Cytoplasmic glycogen, as demonstrated by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positivity, is present in 90% of cases. Ultrastructurally, there is evidence of glycogen and a sparsity of organelles.18

The criteria for distinguishing Ewing's from neuroectodermal tumor of bone have not been well elucidated. In broad terms, however, Ewing's should not demonstrate signs of neuroectodermal differentiation on light or electron microscopy. Although they probably reflect different points in a spectrum of differentiation, the distinction continues to be made, in part because of the poorer prognosis of the neuroectodermal tumors of bone.136

The other differentials to be considered are metastatic neuroblastoma and chloroma in patients younger than 5 years of age and lymphoma in older patients. Mesenchymal chondrosarcomas and the small cell variant of osteosarcoma are distinguished primarily by the appropriate matrix production.

MANAGEMENT. Induction multiagent chemotherapy followed by radical local surgery or radiation therapy has resulted in improved 5-year survival rates of up to 74%. Unfortunately, 17% to 20% of survivors subsequently develop a second primary, most commonly osteosarcoma.137,138 As a result of factors such as improved local control and postradiation malignancies, surgery is currently favored over radiation therapy for resectable lesions.139

Hematopoietic and Histiocytic Lesions

MYELOMA. Multiple myeloma and more rarely solitary plasmacytoma may involve orbital bone.140–143 These tumors affect those older than 50 years and present with a subacute onset of pain and proptosis. In the case of multiple myeloma, there are usually systemic manifestations such as bone pain, fever, and fatigue, as well as urinary and serum protein abnormalities. Radiologically, an osteolytic area with a contiguous soft tissue mass is the rule. Histologically, the tumors are composed of broad sheets of malignant plasma cells varying in appearance from mature to blastlike.40

LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCYTOSIS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis consists of a variety of syndromes resulting from the proliferation of Langerhans cells. Localized bone involvement (eosinophilic granuloma) is prevalent in boys ages 3 to 10 years. These children characteristically develop proptosis as a result of focal lytic superolateral lesions associated with soft tissue expansion.144–146 We have seen six cases of localized Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and each demonstrated a characteristic CT appearance of a central radiolucent area with an enhancing rim (Fig. 12). Histologically, there is a granulomatous and histiocytic infiltrate with Langerhans cells and prominent eosinophils.147 Localized periorbital disease is responsive to curettage, intralesional steroid injections, or low-dose radiation therapy. The prognosis is poorer in younger patients with visceral involvement.

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumor is usually found in the long bones in the third to fifth decades, with a slight female predominance.40 It rarely occurs in the sphenoid, temporal, or ethmoid bones, with a primary orbital site reported on one occasion.52 Most cases with orbital involvement originate in the sphenoid; patients present with headaches, diplopia, decreased vision, and multiple cranial nerve palsies.148,149 The sphenoidal lesions are radiologically apparent as either lytic or soft tissue masses eroding the sella.

This friable tumor is composed of uniformly distributed osteoclast-like giant cells. Occasionally, a giant cell tumor may display clinical and histologic evidence of malignancy and metastasize to the lungs.19,67

There is a 30% to 50% recurrence rate after curettage, so the goal is complete excision if possible. Radiation therapy has been reserved for inaccessible lesions because of the risk of inducing malignancy.148,149

VASCULAR TUMORS

Aside from one report of a hemangioendothelioma of orbital bone, the only other vascular bony tumor described in the orbit has been the hemangioma. The hemangioendothelioma presented as an aggressive and lytic infiltrative lesion that recurred after resection.150

Intraosseous Hemangioma

These benign vascular tumors of bone, like their counterparts in the orbital soft tissues, are probably hamartomatous in origin. They are common in the calvarium and spine but rare in the orbit. Any of the orbital bones may be involved, although the frontal bone is the most common site. Including one case of our own, there are 20 cases in the literature. The average age is in the fifth decade, with a slight female preponderance.151–155

PRESENTATION. A slowly developing orbital mass, often associated with pain or tenderness, is typical. There may be a palpable mass in the anterior orbit.

IMAGING. Intraosseous hemangiomas present as well-defined, radiolucent masses that expand the inner and outer tables of the bone, often in an asymmetric fashion. Approximately half show the classic picture of a sunburst, striated, or honeycombed internal pattern (Fig. 13). On selective angiography, they appear as a tangle of vessels.155

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The specimen consists of soft, violaceous masses with intervening trabeculae of reactive bone. Microscopically, most are cavernous hemangiomas with large endothelial-lined, blood-filled vascular spaces.156

MANAGEMENT. Surgical treatment consists of excision with a rim of normal bone. Preoperative angiography should be performed and strong consideration given to embolization before resection, because these tumors can bleed in a profuse and persistent manner.155

MISCELLANEOUS

There have been two reports of intramedullary lipoma of the frontal bone that led to chronic painless expansion simulating fibrous dysplasia.157 There have also been reports of intraosseous myxoma presenting in a similar fashion.158,159 Both malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma can rarely arise in orbital bone, often as postradiation neoplasms.160–163