|

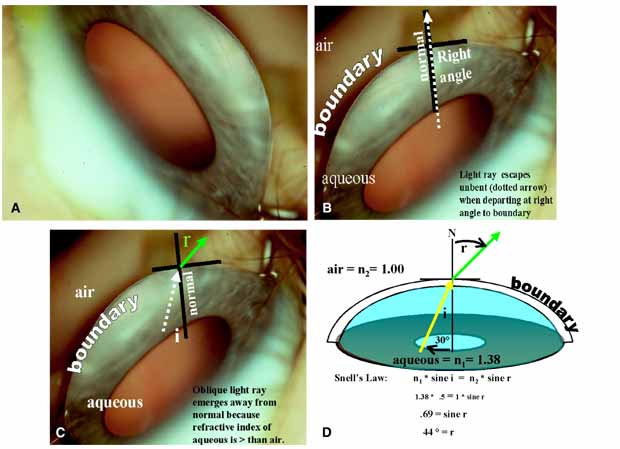

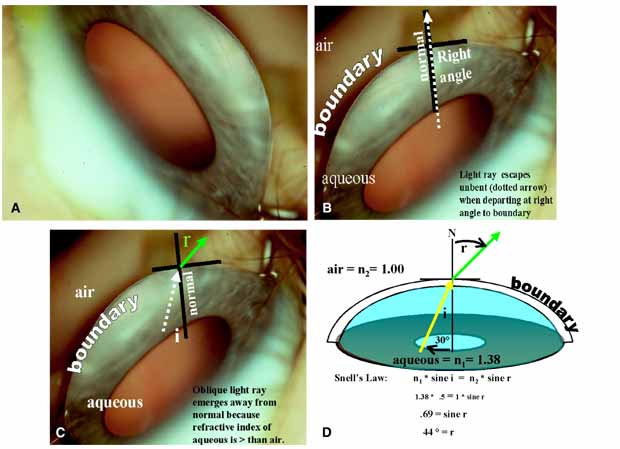

| Fig. 2 Geometrical optics: why you cannot normally see the anterior chamber angle. A. Despite much effort, it is impossible to see into the chamber angle without additional means. This figure is an eye with a very deep anterior chamber and wide-open angle, but without gonioscopy the angle cannot be seen because of the total internal reflection of light rays that originate from the far recesses of the chamber angle. Every ophthalmologist is a lifetime student of optics and should review why this occurs. B. Why is it that lights rays can emerge anywhere from the anterior chamber except the angle? It is best to start with a simple unaltered light ray that emanates from the anterior chamber. A light ray parallel to the normal exits from the anterior chamber unchanged (not bent) when it exits the interface boundary. Obviously a light ray from the scleral spur is not able to escape parallel to a constructed normal. C. An incident light ray that approaches the normal (dotted white arrow) obliquely exits from the anterior chamber bent or refracted when it leaves the interface boundary. A substances index of refraction, n, defines how much it will bend light (n of aqueous = 1.38 and air n = 1.0). Aqueous bends light more than air. When a light ray passes from a medium of higher to lower index of refraction, the ray is bent away from the normal. Because the index of refraction of air is less then aqueous, the light rays are bent away from the normal and simultaneously away from the examiner. i = angle of incidence; r = angle of refraction. D. The amount the ray is bent is dependent on Snell's law. In this example it is determined an incident 30-degree ray of light is bent or refracted 44 degrees away from the normal as it emerges from the boundary of the cornea and air. The obvious problem is the more the incident angle is increased; the emergent ray is refracted away from the examiner. (Figure continues.) |