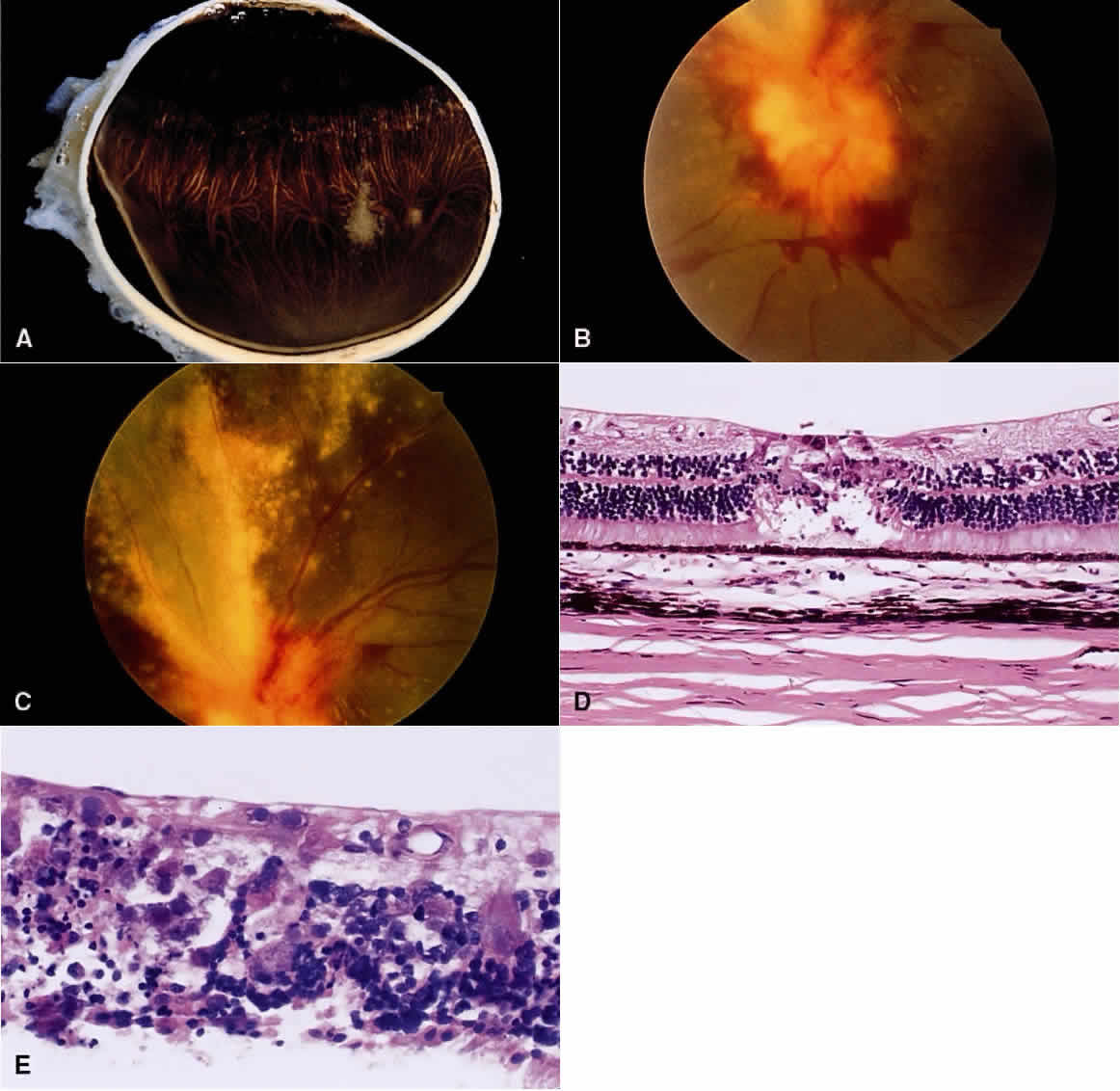

1. Chan C-C, Roberge FG, Whitcup SM et al: 32 cases of sympathetic ophthalmia. A retrospective study at the National

Eye Institute, Bethesda, Md. Arch Ophthalmol 113:597, 1995 2. Fries PD, Char DH, Crawford JB et al: Sympathetic ophthalmia complicating helium ion irradiation of a choroidal

melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol 105:1561, 1987 3. Gass JDM: Sympathetic ophthalmia following vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 93:552, 1982 4. Kinyoun JL, Bensinger RE, Chuang EL: Thirty-year history of sympathetic ophthalmia. Ophthalmology 90:59, 1983 5. Sharp DC, Bell RA, Patterson E et al: Sympathetic ophthalmia. Histopathologic and fluorescein angiographic correlation. Arch Ophthalmol 102:232, 1984 6. Lubin JR, Albert DM: Early enucleation in sympathetic ophthalmia. Ocul Inflam Ther 1:47, 1983 7. Stafford WR: Sympathetic ophthalmia. Report of a case occurring ten and one-half days

after injury. Arch Ophthalmol 74:521, 1965 8. Kay ML, Yanoff M, Katowitz JA: Sympathetic uveitis development in spite of corticosteroid therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 78:90, 1974 9. Lubin JR, Albert DM, Weinstein M: Sixty-five years of sympathetic ophthalmia. A clinicopathologic review

of 105 cases (1913-1978). Ophthalmology 87:109, 1980 10. Reynard M, Riffenburgh RS, Maes EF: Effect of corticosteroid treatment and enucleation on the visual prognosis

of sympathetic ophthalmia. Am J Ophthalmol 96:290, 1983 11. Rao NA, Robin J, Hartmann D et al: The role of the penetrating wound in the development of sympathetic ophthalmia. Experimental

observations. Arch Ophthalmol 101:102, 1983 12. Albert DM, Diaz-Rohena R: A historical review of sympathetic ophthalmia and its epidemiology. Surv Ophthalmol 34:1, 1989 13. Chan C-C, BenEzra D, Hsu S-M et al: Granulomas in sympathetic ophthalmia and sarcoidosis. Immunohistochemical

study. Arch Ophthalmol 103:198, 1985 14. Jakobiec PA, Marboe CC, Knowles DM et al: Human sympathetic ophthalmia. An analysis of the inflammatory infiltrate

by hybridoma-monoclonal antibodies, immunochemistry, and correlative

electron microscopy. Ophthalmology 90:76, 1983 15. Muller-Hermelink HK, Kraus-Mackiw E, Daus W: Early stage of human sympathetic ophthalmia. Histologic and immunopathologic

findings. Arch Ophthalmol 102:1353, 1984 16. Chan C-C: Relationship between sympathetic ophthalmia, phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis, and

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Ophthalmology 95:619, 1988 17. Easom HA, Zimmerman LE: Sympathetic ophthalmia and bilateral phacoanaphylaxis. A clinicopathologic

correlation of the sympathogenic and sympathizing eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 72:9, 1964 18. Fine BS, Gilligan JH: The Vogt-Koyanagi syndrome. A variant of sympathetic ophthalmia: report

of two cases. Am J Ophthalmol 43:433, 1957 19. Marak GE Jr: Recent advances in sympathetic ophthalmia. Surv Ophthalmol 24:141, 1979 20. Yanoff M: Pseudo-sympathetic uveitis. Trans Pa Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 30:118, 1977 21. Marak GE Jr, Font RL, Zimmerman LE: Histological variations related to race in sympathetic ophthalmia. Am J Ophthalmol 78:935, 1974 22. Inomata H: Necrotic changes of choroidal melanocytes in sympathetic ophthalmia. Arch Ophthalmol 106:239, 1988 23. Rao NA, Xu 5, Font RL: Sympathetic ophthalmia. An immunohistochemical study

of epithelioid and giant cells. Ophthalmology 92:1660, 1985 24. Font RL, Fine BS, Messmer E et al: Light and electron microscopic study of Dalen-Fuchs nodules in sympathetic

ophthalmia. Ophthalmology 90:66, 1982 25. Green WR, Maumenee AE, Saunders TE et al: Sympathetic uveitis following evisceration. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 76:625, 1972 26. Apple DJ, Mamalis N, Steinmetz RL et al: Phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis associated with extracapsular cataract

extraction and posterior chamber intraocular lens. Arch Ophthalmol 102:1528, 1984 27. Chishti M, Henkind P: Spontaneous rupture of anterior lens capsule (phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis). Am J Ophthalmol 69:264, 1970 28. Caudill JW, Streeten BW, Tso MOM: Phacoanaphylactoid reaction in persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. Ophthalmology 92:1153, 1985 29. Marak GE Jr: Phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol 36:325, 1992 30. Marak GE, Font RL, Alepa FP: Immunopathogenicity of lens crystallins in the production of experimental

lens-induced granulomatous endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Res 10:33, 1978 31. Yanoff M, Scheie HG: Cytology of human lens aspirate. Its relationship to phacolytic glaucoma

and phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 80:166, 1968 32. Ferry AB, Barnert AH: Granulomatous keratitis resulting from the use of cyanoacrylate adhesions

for closure of perforated corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol 72:538, 1971 33. Naumann G, Ortbauer R: Histopathology after successful implantation of anterior chamber acrylic

lens. Surv Ophthalmol 15:18, 1970 34. Riddle PJ, Font RL, Johnson FB et al: Silica granuloma of eyelid and ocular adnexa. Arch Ophthalmol 99:683, 1981 35. Naumann GOH, Vulcker HE: Endophthalmitis haemogranulomatosa (Eine spezielle Reaktionsform auf intraokulare

Blutungen). Km Monatsbl Augenheilkd 171:352, 1977 36. Ferry AP: Synthetic fiber granuloma. “Teddy bear” granuloma of the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol 112:1339, 1994 37. Anand R, Font RL, Fish RH et al: Pathology of cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with sustained release intravitreal

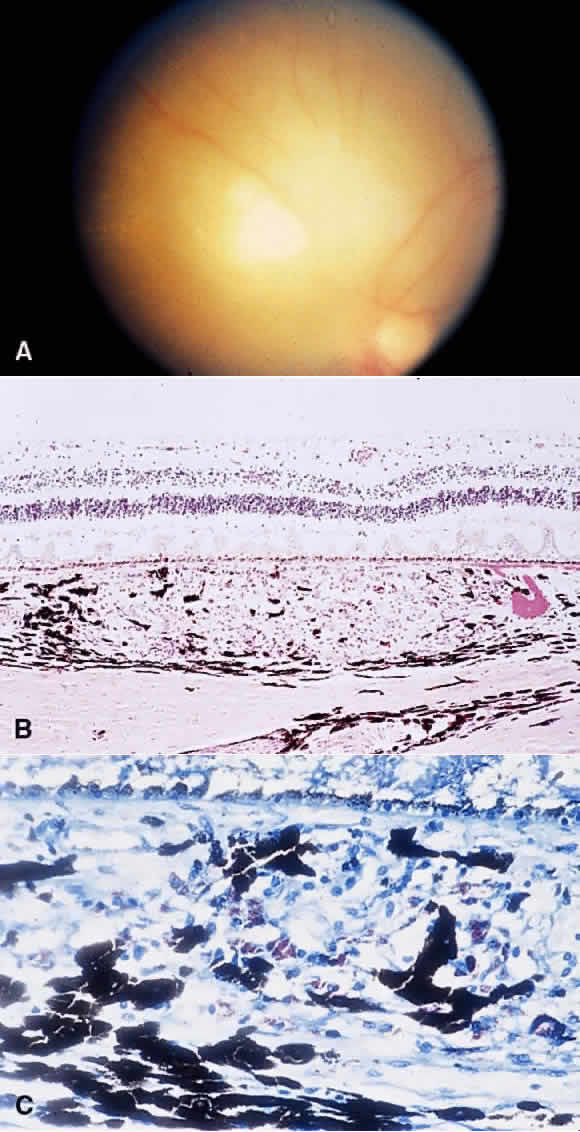

ganciclovir. Ophthalmology 100:1032, 1993 38. Yoser SL, Forster DJ, Rao NA: Systemic viral infections and their retinal and choroidal manifestations. Surv Ophthalmol 37:313, 1993 39. Rummelt V, Rummelt C, Jahn G et al: Triple retinal infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1, cytomegalovirus, and

herpes simplex virus type 1. Light and electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization. Ophthalmology 101:270, 1994 40. Smith ME: Retinal involvement in adult cytomegalic inclusion disease. Arch Ophthalmol 72:44, 1964. 41. deVenecia G, Rhein GMZ, Pratt M et al: Cytomegalic inclusion retinitis in an adult. A clinical, histopathologic

and ultrastructural study. Arch Ophthalmol 86:44, 1971 42. Friedman AH: The retinal lesions of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 82:447, 1984 43. Grossniklaus HE, Frank KE, Tomsak RL: Cytomegalovirus retinitis and optic neuritis in acquired immune deficiency

syndrome. Report of a case. Ophthalmology 94:1601, 1987 44. Guarda LA, Luna MA, Smith JL et al: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: postmortem findings. Am J Clin Pathol 81:549, 1984 45. Kestelyn P, Van de Perre P, Rouvroy D et al: A prospective study of the ophthalmologic findings in the acquired immune

deficiency syndrome in Africa. Am J Ophthalmol 100:230, 1985 46. Schuman JS, Orellana J, Friedman AH et al: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Surv Ophthalmol 31:384, 1987 47. Rabb MF, Jampol LM, Fish RH et al: Retinal periphlebitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

and cytomegalovirus retinitis mimics acute frosted retinal periphlebitis. Arch Ophthalmol 110:1257, 1992 48. Glasgow BJ, Weisberger AK: A quantitative and cartographic study of retinal microvasculopathy in acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 118:46, 1994 49. Pepose JS, Newman C, Bach MC et al: Pathologic features of cytomegalovirus retinopathy after treatment with

the antiviral agent acyclovir. Ophthalmology 94:414, 1987 50. Hennis HL, Scott AA, Apple DJ Jr: Cytomegalovirus (clinicopathologic review). Surv Ophthalmol 34:193, 1989 51. Karbassi M, Raizman MB, Schuman JS: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Surv Ophthalmol 36:395, 1992 52. Kupperman BD, Quiceno JI, Wiley C et al: Clinical and histopathological study of varicella zoster virus in patients

with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 118:589, 1994 53. Kattah JC, Kennerdell JS: Orbital apex syndrome secondary to herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am J Ophthalmol 85:378, 1978 54. Wenkel H, Rummelt V, Fleckenstein B et al: Detection of varicella zoster virus DNA and viral antigen in human eyes

after herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology 105: 1323, 1998 55. Naumann G, Gass JDM, Font RL: Histopathology of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am J Ophthalmol 65:533, 1968 56. Hedges TR III, Albert DM: The progression of the ocular abnormalities of herpes zoster. Histopathologic

observations of nine cases. Ophthalmology 89:165, 1982 57. Helm CJ, Holland GN: Ocular tuberculosis. Surv Ophthalmol 38:229, 1993 58. Berinstein DM, Gentile RC, McCormick SA et al: Primary ocular tuberculoma. Arch Ophthalmol 115:430, 1997 59. Sarvanathan N, Wiselka M, Bibby K: Intraocular tuberculosis without detectable systemic infection. Arch Ophthalmol 116:1386, 1998 60. Bloomfield SE, Mondino B, Gray GF: Scleral tuberculosis. Arch Ophthalmol 94:954, 1976 61. Spaide R, Nattis R, Lipka A et al: Ocular findings in leprosy in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol 100:411, 1985 62. Dana M-R, Hochman MA, Viana MAG et al: Ocular manifestations of leprosy in a noninstitutionalized community in

the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 112:626, 1994 63. Nemeth GG, Fish RH, Itani KM, Yates BE: Hansen's disease. Arch Ophthalmol 110:1482, 1992 64. Chang WJ, Tse DT, Rosa RH et al: Periocular atypical mycobacterial infections. Ophthalmology 106:86, 1999 65. Bullington RH Jr, Lanier JD, Font RL: Nontuberculous mycobacterial keratitis. A report of two cases and review

of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol 110:519, 1992 66. Rosenbaum PS, Mbekeani JN, Kress Y: Atypical mycobacterial panophthalmitis seen with iris nodules. Arch Ophthalmol 116:1524, 1998 67. Winterkorn JMS: Lyme disease: neurologic and ophthalmic manifestations. Surv Ophthalmol 35:191, 1990 68. Karma A, Seppala I, Mikkila H et al: Diagnosis and clinical characteristics of ocular Lyme borreliosis. Am J Ophthalmol 119:127, 1995 69. McCarron MJ, Albert DM: Iridocyclitis and an iris mass associated with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmology 91:1264, 1984 70. Scattergood KD, Green WR, Hirst LW: Scrolls of Descemet's membrane in healed syphilitic interstitial keratitis. Ophthalmology 90:1518, 1983 71. Spektor FE, Eagle RC, Nichols CW: Granulomatous conjunctivitis secondary to treponema pallidum. Ophthalmology 88:863, 1981 72. Arruga J, Valentines J, Mauri F et al: Neuroretinitis in acquired syphilis. Ophthalmology 92:262, 1985 73. Scully RE, Mark EJ, McNeely BU: Mass in the iris and a skin rash in a young man. N Engl J Med 310:972, 1984 74. Margo CE, Hamed LM: Ocular syphilis. Surv Ophthalmol 37:203, 1992 75. Rogers SJ, Johnson BL: Endogenous Nocardia endophthalmitis: report of a case in a patient treated for lymphocytic

lymphoma. Ann Ophthalmol 9:1123, 1977 76. Golnik KC, Marotto ME, Fanous MM et al: Ophthalmic manifestations of Rochalimaea species. Am J Ophthalmol 118:145, 1994 77. Warren K, Goldstein E, Hung VS et al: Use of retinal biopsy to diagnose Bartonella (formerly Rochalimaea) henselae retinitis in an HIV-infected patient. Arch Ophthalmol 116:937, 1998 78. Dondey JC, Sullivan TJ, Robson JMB et al: Application of polymerase chain reaction assay in the diagnosis of orbital

granuloma complicating atypical oculoglandular cat scratch disease. Ophthalmology 104:1174, 1997 79. Cunningham ET, McDonald HR, Schatz H et al: Inflammatory mass of the optic nerve head associated with systemic Bartonella henselae infection. Arch Ophthalmol 115:1596, 1997 80. Reed JB, Scales DK, Wong MT et al: Bartonella henselae Neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease. Ophthalmology 105:459, 1998 81. Ulrich GG, Waecker NJ, Meister SJ et al: Cat scratch disease associated with neuroretinitis in a 6-year old girl. Ophthalmology 99:246, 1992 82. Steinemann TL, Sheikholeslami MR, Brown HH et al: Oculoglandular tularemia. Arch Ophthalmol 117:132, 1999 83. Williams JG, Edward DP, Tessler HH et al: Ocular manifestations of Whipple disease, an atypical presentation. Arch Ophthalmol 116:1232, 1998 84. Sponsler TA, Sassani JW, Johnson LN et al: Ocular invasion in mucormycosis. Surv Ophthalmol 36:345, 1992 85. Yohai RA, Bullock JD, Aziz AA et al: Survival factors in rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Surv Ophthalmol 39:3, 1994 86. Griffin IR, Pettit TH, Fishman LS et al: Bloodborne Candida endophthalmitis. A clinical and pathologic study of 21 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 89:450, 1973 87. Donahue SP, Greven CM, Zuravleff JJ et al: Intraocular candidiasis in patients with candidemia. Ophthalmology 101:1302, 1994 88. Fine BS: Intraocular mycotic infections. Lab Invest 11:1161, 1962 89. McDonnell PJ, McDonnell JM, Brown RH et al: Ocular involvement in patients with fungal infections. Ophthalmology 92:706, 1985 90. Cunningham ET, Seiff SR, Berger TG et al: Intraocular coccidioidomycosis diagnosed by skin biopsy. Arch Ophthalmol 116:674, 1998 91. Hiss PW, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ: Solitary retinovitreal abscess as the initial manifestation of cryptococcosis. Ophthalmology 95:162, 1988 92. Charles NC, Boxrud CA, Small EA: Cryptococcosis of the anterior segment in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 99:813, 1992 93. Barr CC, Gamel JW: Blastomycosis of the eyelid. Arch Ophthalmol 104:96, 1986 94. Callanan D, Fish GE, Anand R: Reactivation of inflammatory lesions in ocular histoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 116:470, 1998 95. Moorthy RS, Rao NA, Sidkaro Y et al: Coccidioidomycosis iridocyclitis. Ophthalmology 101:1923, 1994 96. Dortzbach RK, Segrest DR: Orbital aspergillosis. Ophthalmic Surg 14:240, 1983 97. Glasgow BJ, Brown HH, Foos RY: Miliary retinitis in coccidioidomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 104:24, 1987 98. Reidy JJ, Sudesh S, Klafter AB et al: Infection of the conjunctiva by Rhinosporidium seeberi. Surv Ophthalmol 41:409, 1997 99. Savino DF, Margo CE: Conjunctival rhinosporidiosis. Light and electron microscopic study. Ophthalmology 90:1482, 1983 100. Font RL, Jakobiec FA: Granulomatous necrotizing retinochoroiditis caused by Sporotrichum schenkii. Report of a case including immunofluorescence and electron microscopical

studies. Arch Ophthalmol 94:1513, 1976 101. Lou P, Kazdan J, Basu PK: Ocular toxoplasmosis in three consecutive siblings. Arch Ophthalmol 96:613, 1978 102. Fung JC, Clogston A, Swenson P et al: Serologic diagnosis of toxoplasmosis with emphasis on the detection of

toxoplasma-specific immunoglobulin M antibodies. Am J Clin Pathol 83:196, 1985 103. Doft BH, Gass JDM: Punctate outer retinal toxoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 103:1332, 1985 104. Michelson JB. Shields JA, McDonald PR et al: Retinitis secondary to acquired systemic toxoplasmosis with isolation of

the parasite. Am J Ophthalmol 86:548, 1978 105. Grossniklaus HE, Specht CS, Allaire G et al: Toxoplasma gondii retinochoroiditis and optic neuritis in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Report

of a case. Ophthalmology 97:1342, 1990 106. Andres TL, Dorman SA, Winn WC Jr et al:Immunohistochemical demonstration of Toxoplasma gondii. Am J Clin Pathol 75:431, 1981 107. Wilder HC: Toxoplasma chorioretinitis in adults. Arch Ophthalmol 48:127, 1952 108. O'Connor GR: The roles of parasite invasion and of hypersensitivity in the pathogenesis

of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Ocul Inflam Ther 1:37, 1983 109. Rao NA, Font RL: Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Electron-microscopic and immunofluorescence

studies of formalin-fixed tissue. Arch Ophthalmol 95:273, 1977 110. Rockey IH, Donnelly II, Stromberg BE et al: Immunopathology of Toxocara canis and ascaris SUUM infections of the eye: the role of the eosinophil. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 18:1172, 1979 111. Berrocal J: Prevalence of Toxocara canis in babies and in adults as determined by the ELISA test. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 78:376, 1980 112. Watzke RC, Oaks JA, Folk JC: Toxocara canis infection of the eye. Correlation of clinical observations with developing

pathology in the primate model. Arch Ophthalmol 102:282, 1984 113. Wilder HC: Nematode endophthalmitis. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 54:99, 1950 114. Spaeth GL, Adams RE, Soffe AM: Treatment of trichinosis. Case report. Arch Ophthalmol 71:359, 1964 115. Gendelman D, Blumberg R, Sadun A: Ocular Loa loa with cryoprobe extraction of subconjunctival worm. Ophthalmology 91:300, 1984 116. Gass JDM, Gilbert WR Jr, Guerry RK et al: Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Ophthalmology 85:521, 1978 117. Kazacos KR, Raymond LA, Kazacos EA et al: The raccoon ascarid. A probable cause of human ocular larva migrans. Ophthalmology 92:1735, 1985 118. Phelan MJ, Johnson MW: Acute posterior ophthalmomyiasis interna treated with photocoagulation. Am J Ophthalmol 119:106, 1995 119. Gass JD: Subretinal migration of a nematode in a patient with diffuse unilateral

subacute neuroretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 114:1526, 1996 120. Custis PH, Pakalnis VA, Klintworth GK et al: Posterior internal ophthalmomyiasis. Identification of a surgically removed Cuterebra larva by scanning electron microscopy. Ophthalmology 90:1583, 1983 121. Goodart RA, Riekhof FT, Beaver PC: Subretinal nematode. An unusual etiology for uveitis and retinal detachment. Retina 5:87, 1985 122. Sorr EM: Meandering ocular toxocariasis. Retina 4:90, 1984 123. Zinn KM, Guillory SL, Friedman AH: Removal of intravitreous cysticerci from the surface of the optic nerve

head. A pars plana approach. Arch Ophthalmol 98:714, 1980 124. Kruger-Leite E, Jalkh AE, Quiroz H et al: Intraocular cysticercosis. Am J Ophthalmol 99:252, 1985 125. Beri S, Vajpayee RB, Dhingra N et al: Managing anterior chamber cysticercosis by viscoexpression: a new surgical

technique. Arch Ophthalmol 111:1278, 1994 126. Morales AG, Croxatto JS, Crovetto L et al: Hydatid cyst of the orbit. A review of 35 cases. Ophthalmology 95:1027, 1988 127. Manschot WA: Coenurus infestation of eye and orbit. Arch Ophthalmol 94:961, 1976 128. Jakobiec FA, Gess L, Zimmerman LE: Granulomatous dacryoadenitis caused by Schistosoma haematobium. Arch Ophthalmol 95:278, 1977 129. Collison JMT, Miller NR, Green WR: Involvement of orbital tissues by sarcoid. Am J Ophthalmol 102:302, 1986 130. Asdourian GK, Goldberg MF, Busse BJ: Peripheral retinal neovascularization in sarcoidosis. Arch Ophthalmol 93:787, 1975 131. Gass JDM, Olson CL: Sarcoidosis with optic nerve and retinal involvement. Arch Ophthalmol 94:945, 1976 132. Westlake WW, Heath JD, Spalton DJ: Sarcoidosis involving the optic nerve and hypothalamus. Arch Ophthalmol 113:669, 1995 133. Nichols CW, Mishkin M, Yanoff M: Presumed orbital sarcoidosis: report of a case followed by computerized

axial tomography and conjunctival biopsy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 76:67, 1978 134. Peterson EA, Hymas DC, Pratt DV et al: Sarcoidosis with orbital tumor outside the lacrimal gland. Initial manifestations

in 2 elderly white women. Arch Ophthalmol 116:804, 1998 135. Hoover DL, Khan JA, Giangiacomo J: Pediatric ocular sarcoidosis (review). Surv Ophthalmol 30:215, 1986 136. Pertschuk LP, Silverstein E, Friedland J: Immunohistologic diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Am J Clin Pathol 75:350, 1981 137. Baarsma GS, La Hey E, Glasius E et al: The predictive value of serum angiotensin converting enzyme and lysozyme

levels in the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol 104:211, 1987 138. Weinreb RN: Diagnosing sarcoidosis by transconjunctival biopsy of the lacrimal gland. Am J Ophthalmol 97:573, 1984 139. Karcioglu ZA, Brear R: Conjunctival biopsy in sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol 99:68, 1985 140. Nichols CW, Eagle RC Jr, Yanoff M et al: Conjunctival biopsy as an aid in the evaluation of the patient with suspected

sarcoidosis. Ophthalmology 87:287, 1980 141. Saer IB, Karcioglu GL, Karcioglu ZA: Incidence of granulomatous lesions in postmortem conjunctival biopsy specimens. Am J Ophthalmol 104:605, 1987 142. Weinreb RN, Kimura SJ: Uveitis associated with sarcoidosis and angiotensin converting enzyme. Am J Ophthalmol 89:180, 1980 143. Chan C-C, Wetzig RP, Palestine AG et al: Immunohistopathology of ocular sarcoidosis. Report of a case and discussion

of immunopathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol 105:1398, 1987 144. Foster CS, Forstot SL, Wilson LA: Mortality rate in rheumatoid arthritis patients developing necrotizing

scleritis or peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Effects of systemic immunosuppression. Ophthalmology 91:1253, 1984 145. Kleiner RC, Raber IM, Passero FC: Scleritis, pericarditis, and aortic insufficiency in a patient with rheumatoid

arthritis. Ophthalmology 91:941, 1984 146. McGavin DDM, Williamson J, Forrester JV et al: Episcleritis and scleritis: a study of their clinical manifestations and

association with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Ophthalmol 60:192, 1976 147. de la Maza MS, Foster S, Jabbur NS: Scleritis associated with rheumatoid arthritis and with other systemic

immune-mediated diseases. Ophthalmology 101:1281, 1994 148. Watson PG, Hayreb SS: Scleritis and episcleritis. Br J Ophthalmol 60:163, 1976 149. Ross MI, Cohen KL, Peiffer RL et al: Episcleral and orbital pseudorheumatoid nodules. Arch Ophthalmol 101:418, 1983 150. Green WR, Zimmerman LE: Granulomatous reaction to Descemet's membrane. Am J Ophthalmol 64:555, 1967 151. Wolter JR, Johnson FD, Meyer RF et al: Acquired autosensitivity to degenerating Descemet's membrane in a

case with anterior uveitis in the other eye. Am J Ophthalmol 72:782, 1971 152. Holbach LM, Font RL, Naumann GOH: Herpes simplex stromal and endothelial keratitis. Granulomatous cell reactions

at the level of Descemet's membrane, the stroma, and Bowman's

layer. Ophthalmology 97:722, 1990 153. Lubin JR. Loewenstein JI, Frederick AR: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome with focal neurologic signs. Am J Ophthalmol 91:332, 1981 154. Perry HD, Font RL: Clinical and histopathologic observations in severe Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada

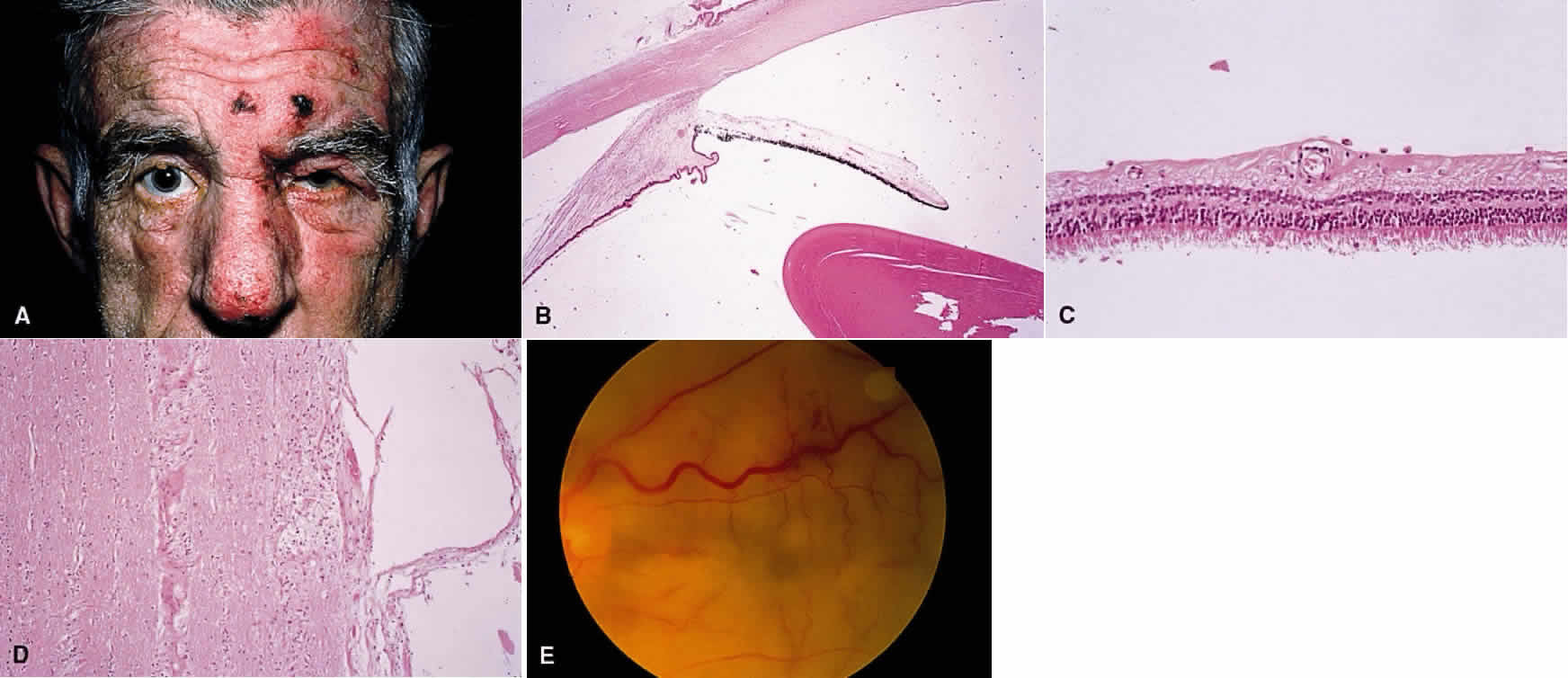

syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 83:242, 1977 155. Kimura R, Sakai M, Okabe H: Transient shallow anterior chamber as initial symptom in Harada's

syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 99:1604, 1981 156. Friedman AH, Deutsch-Sokol RH: Sugiura's sign. Perilimbal vitiligo in the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Ophthalmology 88:1159, 1981 157. Moorthy RS, Inomata H, Rao NA: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 39:265, 1995 158. Rutzen AR, Ortega-Larrocea G, Schwab IR et al: Simultaneous onset of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome in monozygotic twins. Am J Ophthalmol 119:239, 1995 159. Chan C-C, Palestine AG, Kuwabara T et al: Immunopathologic study of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 105:607, 1988 160. Yokoyama MM, Matsui Y, Yamashiroya HM et al: Humoral and cellular immunity studies in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada

syndrome and pars planitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 20:364, 1981 161. Chan C-C, Palestine AG, Nussenblatt RB et al: Anti-retinal auto-antibodies in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, Behçet's

disease, and sympathetic ophthalmia. Ophthalmology 92:1025, 1985 162. Moorthy RS, Chong LP, Smith RE et al: Subretinal neovascular membrane in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 116:164, 1993 163. Rodrigues MM, Palestine AG, Macher AM et al: Histopathology of ocular changes in chronic granulomatous disease. Am J Ophthalmol 96:810, 1983 164. Corberand J, DeLarrard B, Vergnes H et al: Chronic granulomatous disease with leukocytic glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

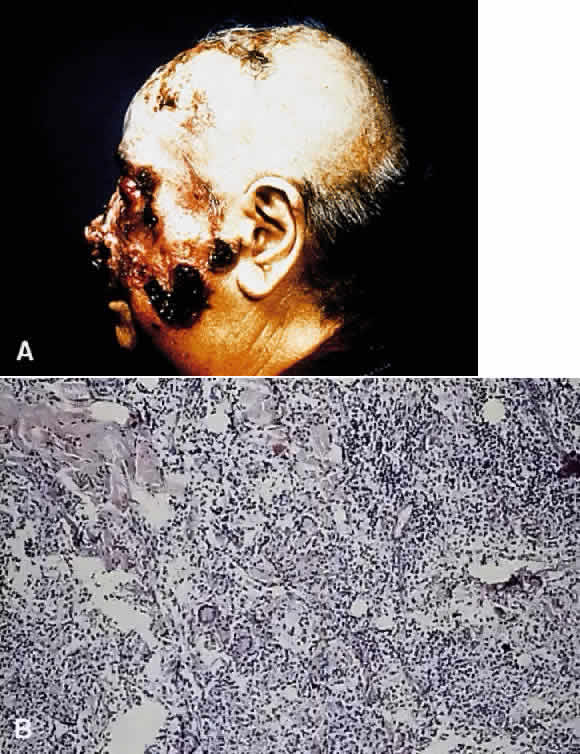

deficiency in a 28-month-old girl. Am J Clin Pathol 70:296, 1978 165. Appen RE, Weber SW, deVenecia G et al: Ocular and cerebral involvement in familial lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Ophthalmol 82:758, 1976 |