CHOROIDAL NEVUS

The choroidal nevus is a benign uveal melanocytic tumor of limited growth potential. The typical lesion (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4) appears as an ill-defined, gray-brown choroidal mass that is usually less than 5 mm in maximal basal diameter and less than 1 mm in thickness. The basal margins of typical lesions often blend into the normal surrounding choroid in a feathered or striate pattern. Drusen and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) pigment clumps commonly develop on the surface of these tumors.

Fluorescein and ICG angiographic features of choroidal nevi have been described by numerous authors.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 Neither fluorescein nor ICG angiography appears to be particularly helpful for evaluation of a typical choroidal nevus. Ophthalmoscopy is usually sufficient to allow one to decide with reasonable certainty whether a small melanotic choroidal tumor is a typical choroidal nevus or an equivocal lesion that may be either a large nevus or small choroidal melanoma. No well-designed clinical study has ever demonstrated significant independent differential diagnostic value of fluorescence angiography for clarifying this differential diagnosis.8

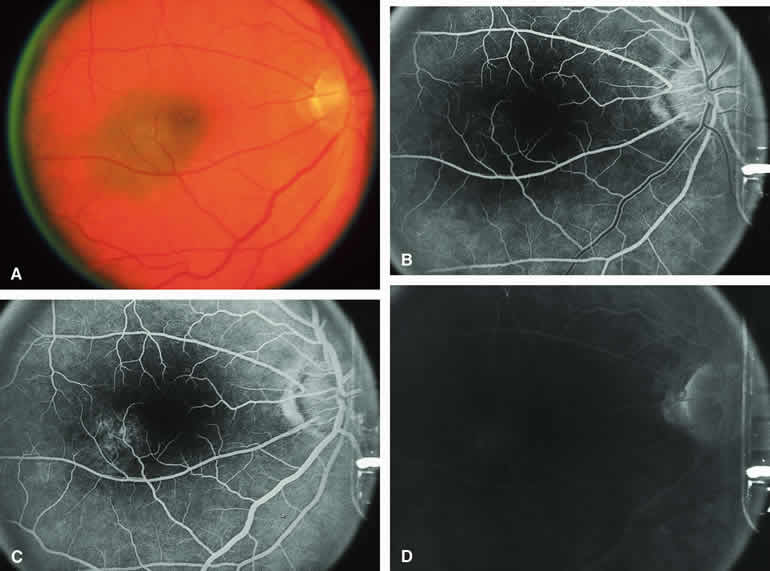

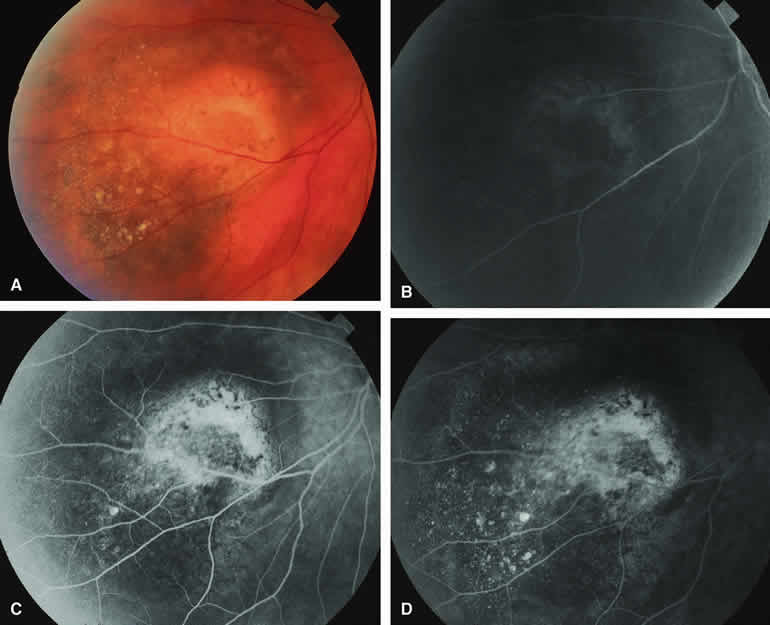

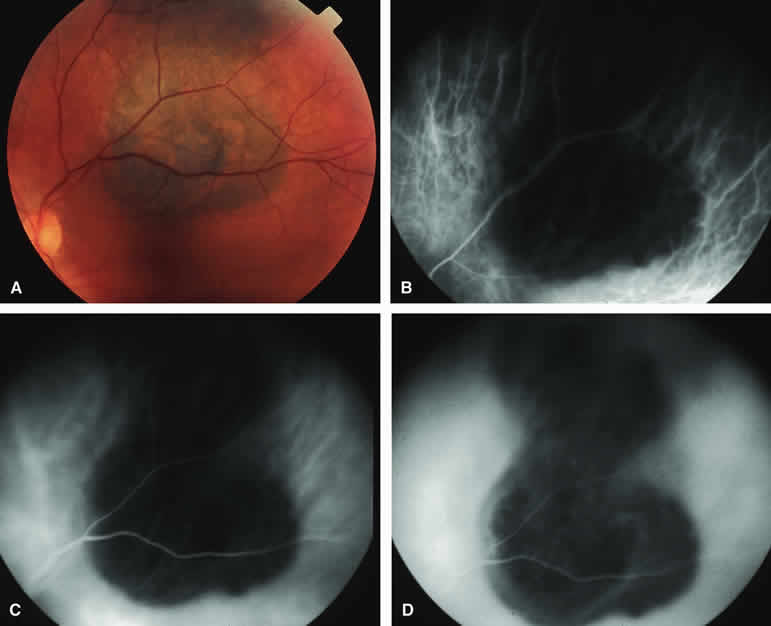

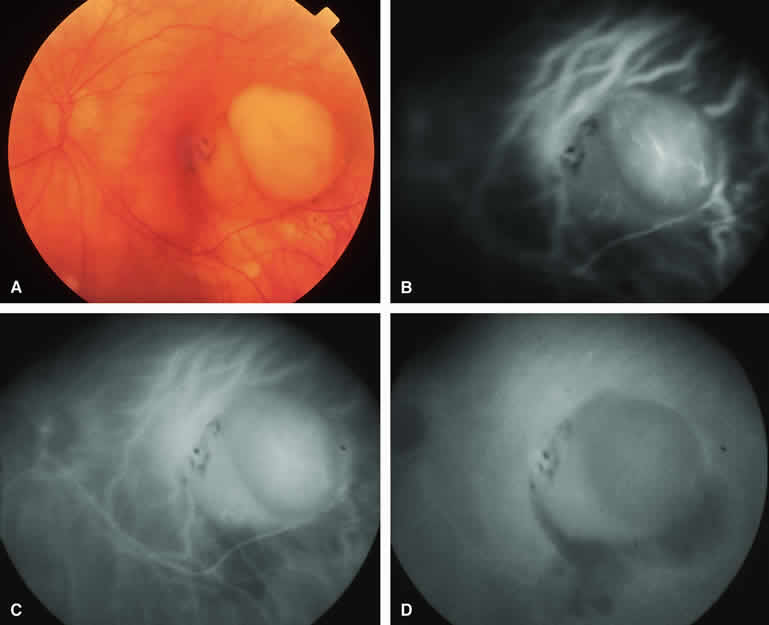

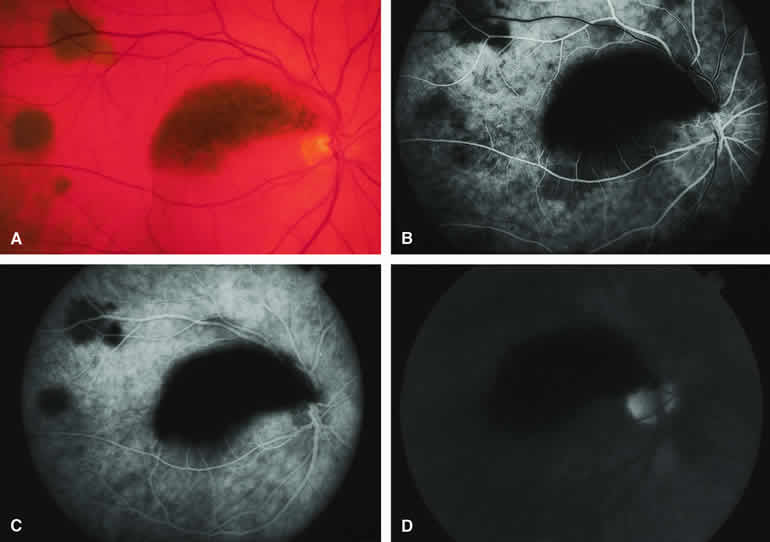

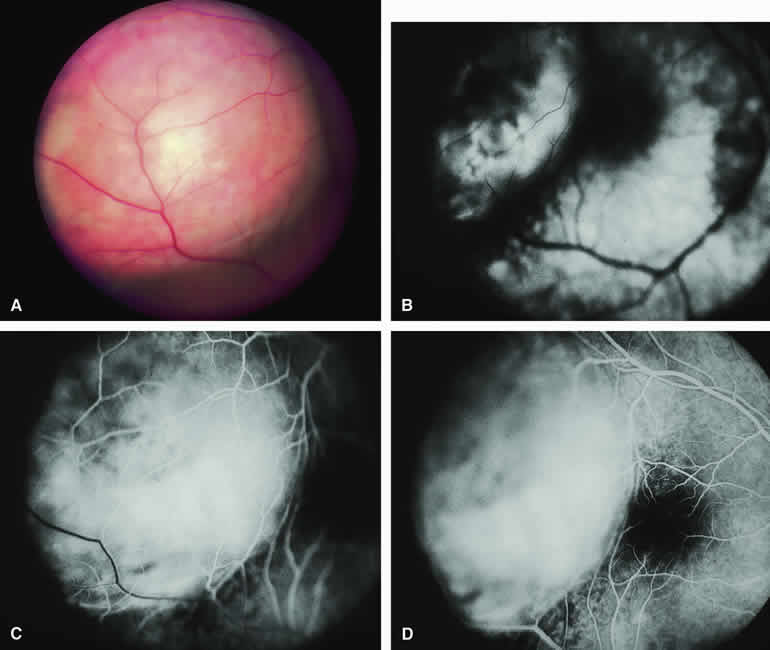

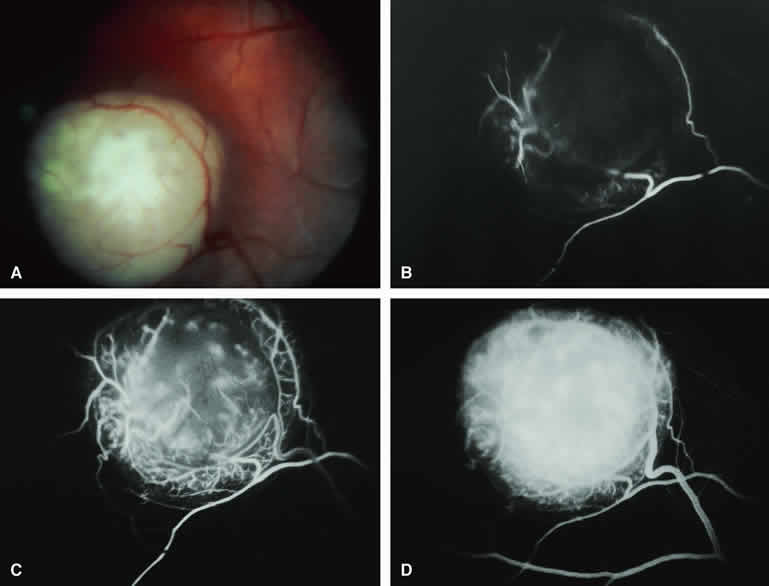

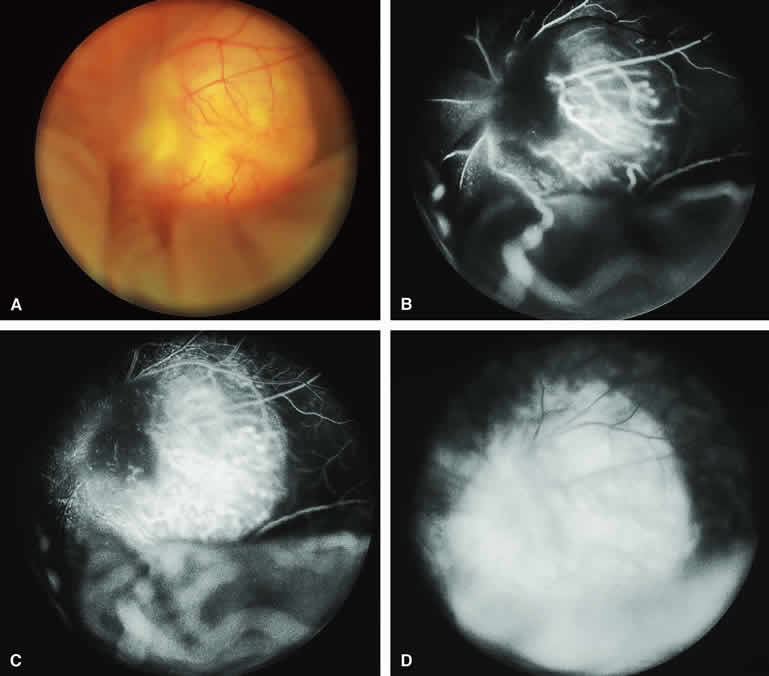

Typical Melanotic Choroidal Nevus

Fluorescein angiography of a typical choroidal nevus with bland surface features (see Fig. 1) shows the entire lesion to be hypofluorescent relative to the adjacent uninvolved choroid throughout the study. No large-caliber choroidal blood vessels are usually identifiable within the lesion. The retinal vasculature overlying the lesion appears well defined and normal on fluorescein angiography.

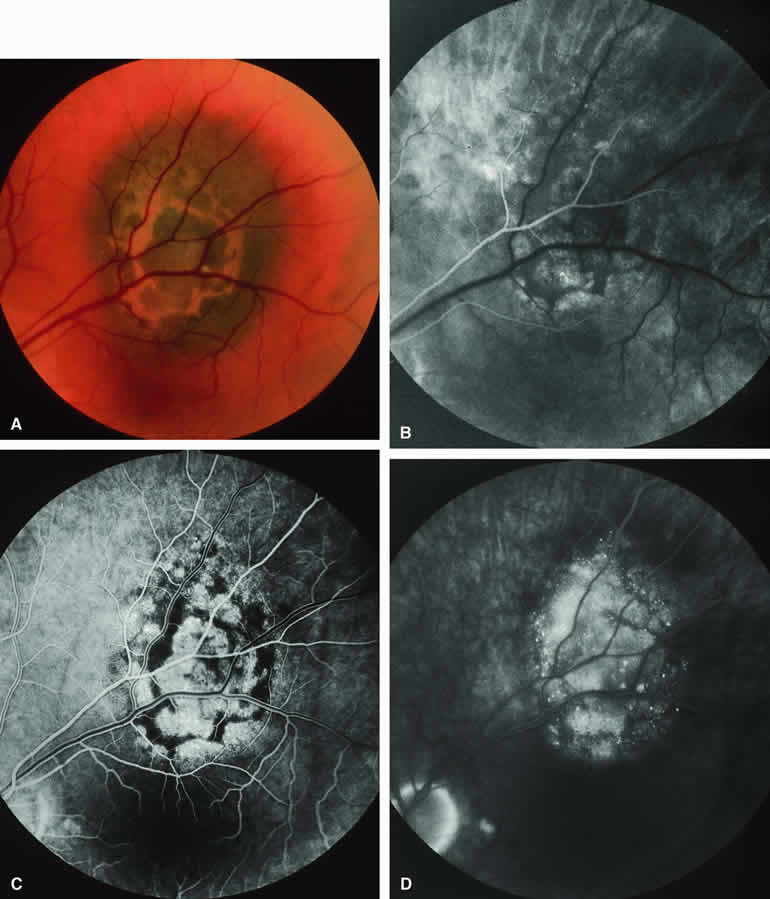

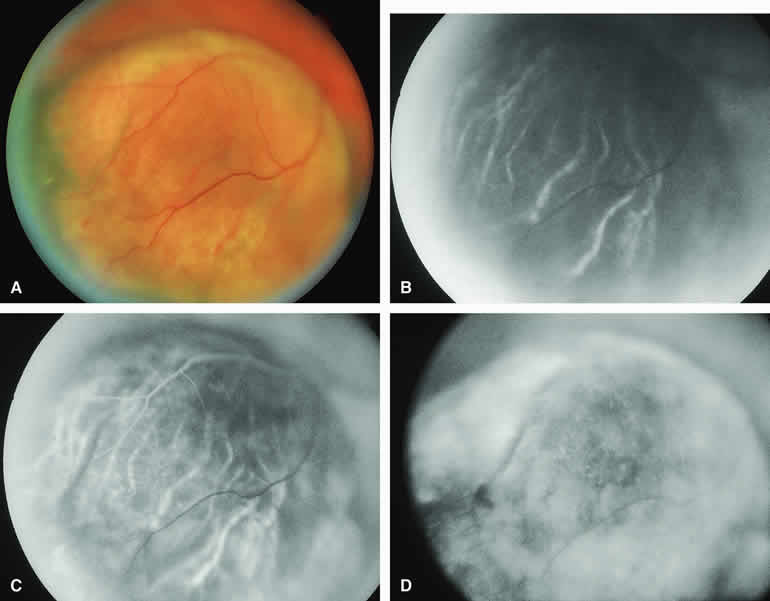

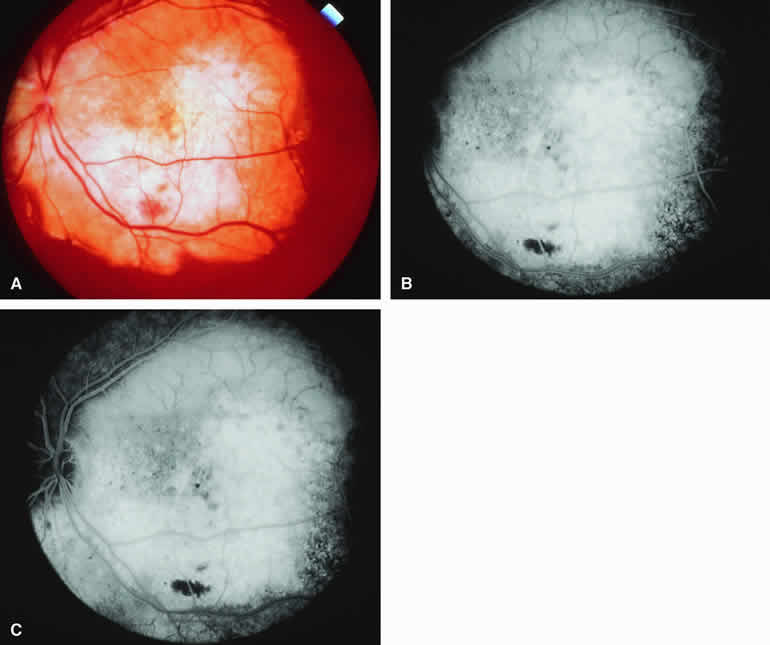

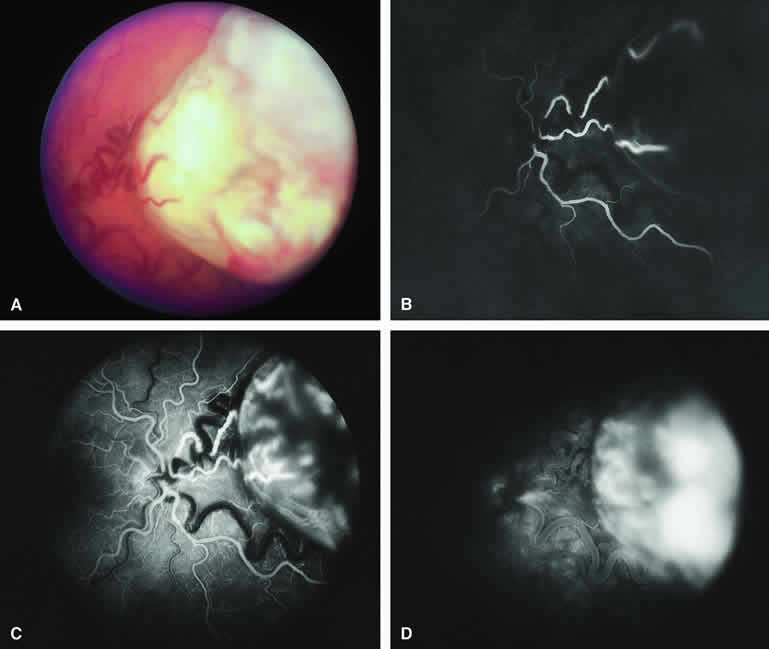

ICG angiography of a typical melanotic choroidal nevus (see Fig. 2) shows better definition of the basal area of the lesion than does fluorescein angiography. The entire lesion appears completely and uniformly dark throughout the ICG angiogram. Only the larger retinal blood vessels overlying the nevus are usually demonstrated on ICG angiography.

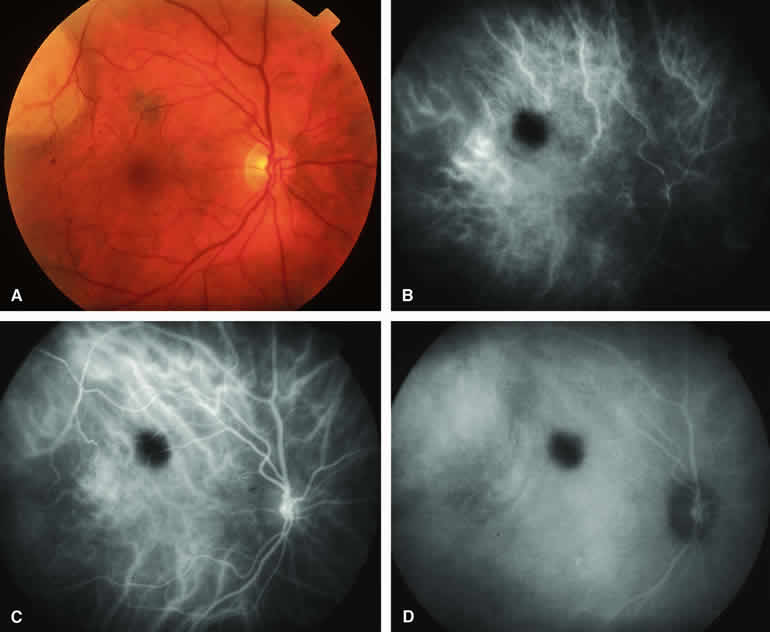

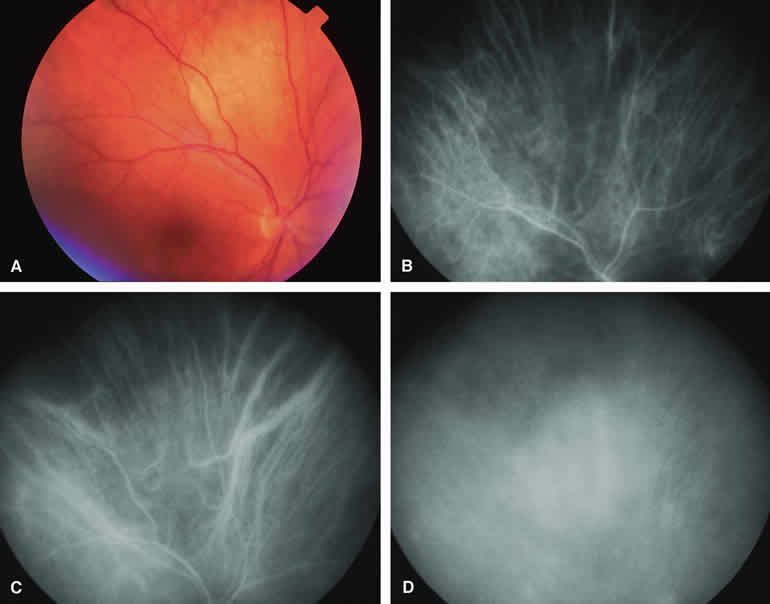

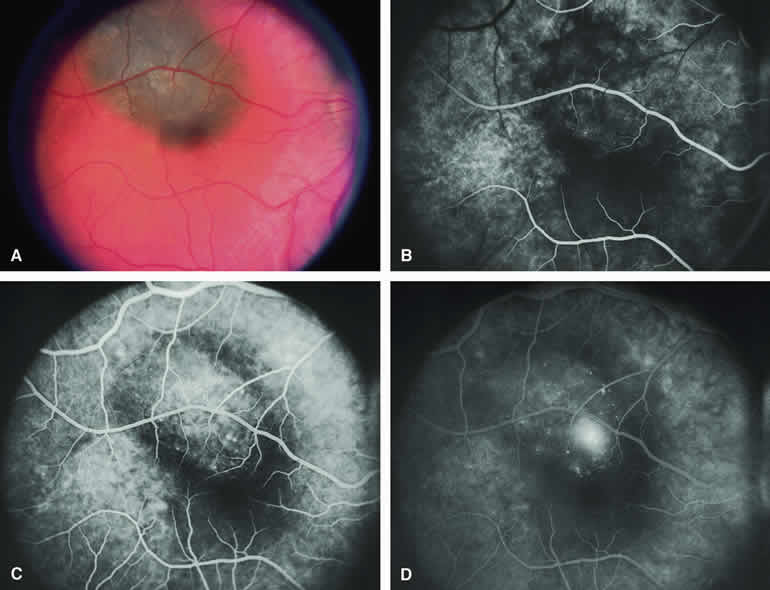

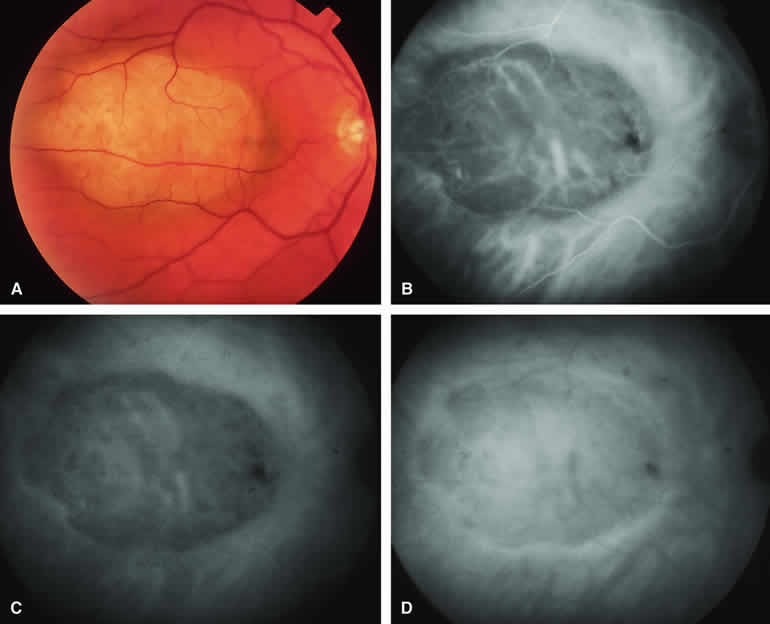

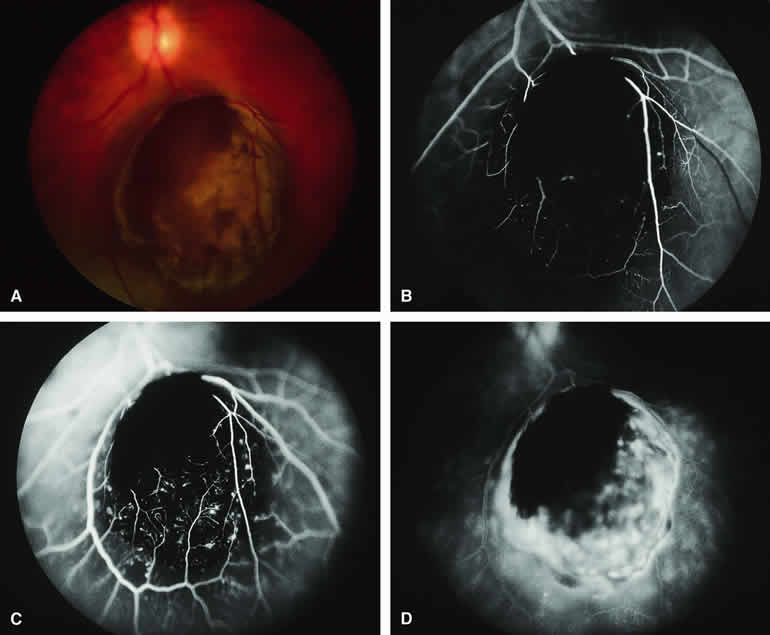

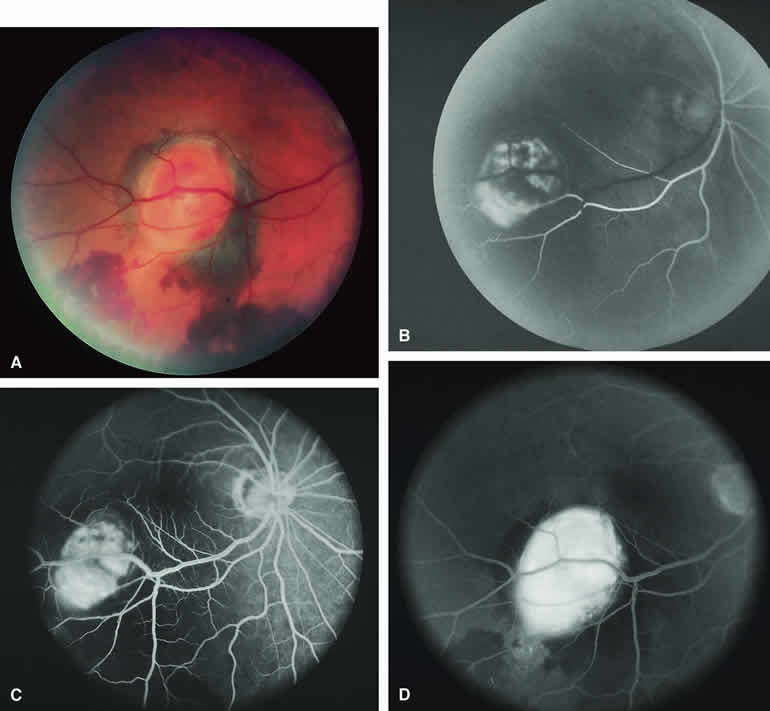

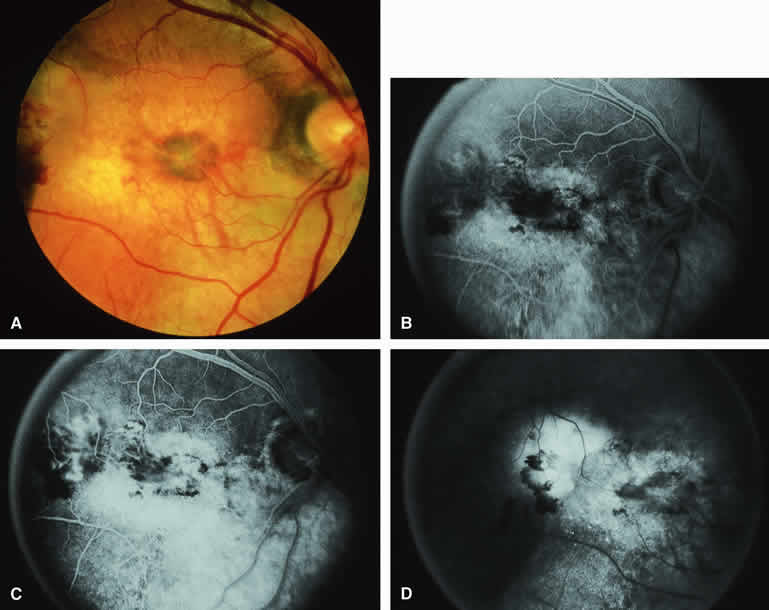

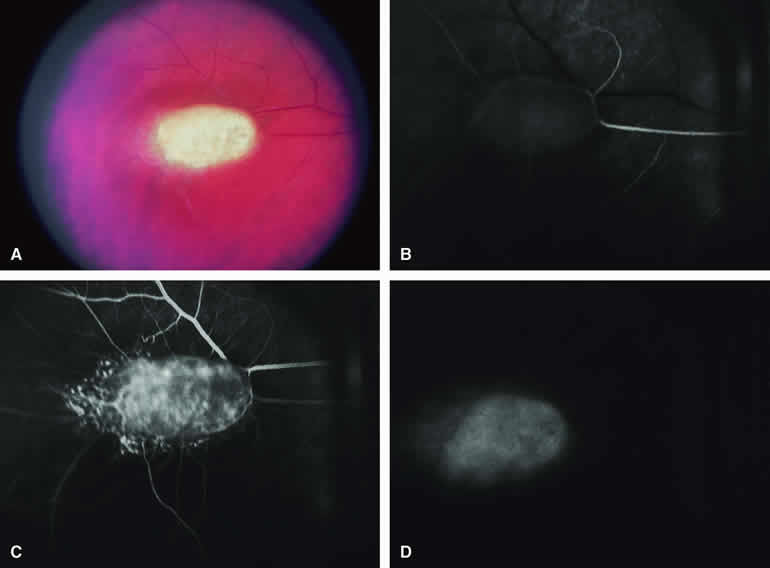

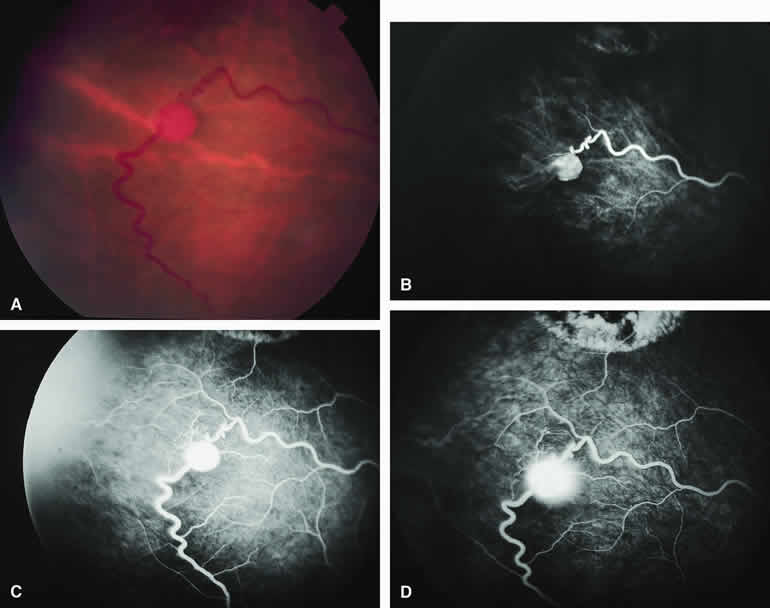

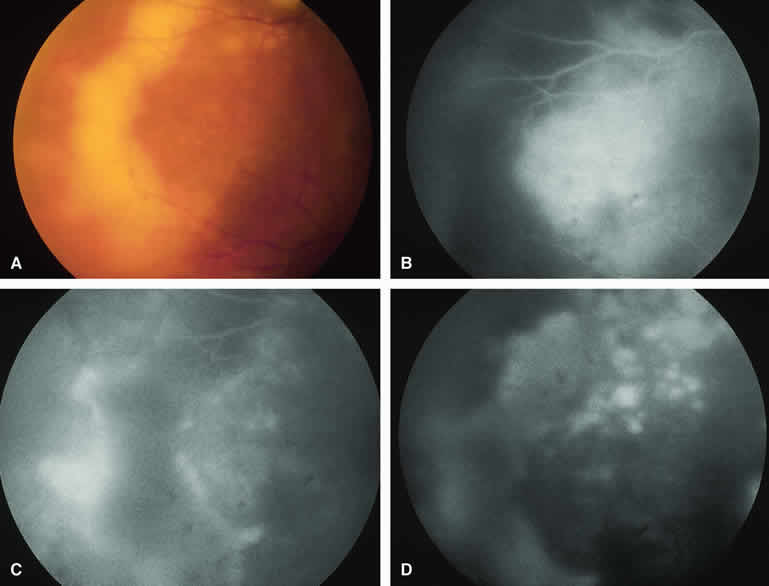

Amelanotic Choroidal Nevus

Approximately 10% to 15% of choroidal nevi are largely or completely amelanotic clinically. Fluorescein and ICG angiography of an amelanotic choroidal nevus (see Fig. 3) tend to show less prominent hypofluorescence of the lesion than they do with darkly melanotic nevi. Because of the lack of intracellular melanin pigment within the nevus cells, some large-caliber choroidal blood vessels running through the nevus may be visible in the region of the mass (see Fig. 3B and C). These choroidal blood vessels are better defined by ICG angiography than by fluorescein angiography. Amelanotic choroidal nevi often appear mildly hyperfluorescent in late-phase frames (see Fig. 3D).

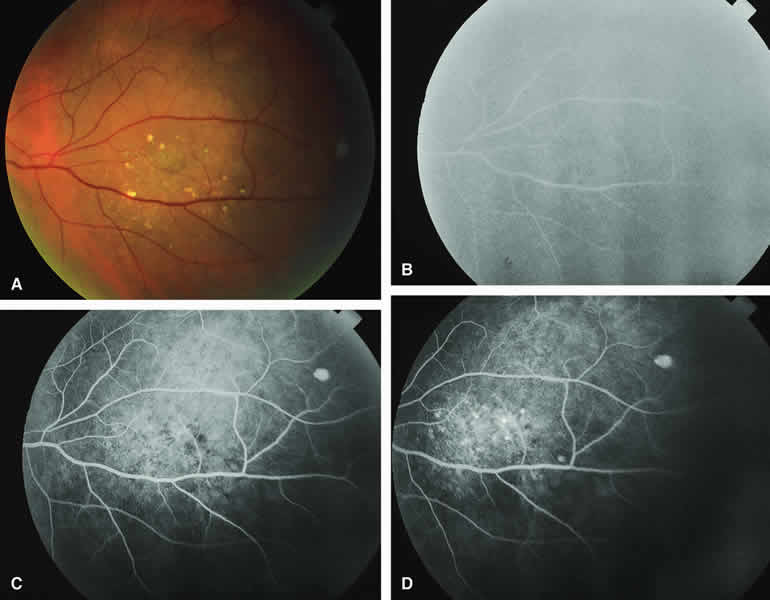

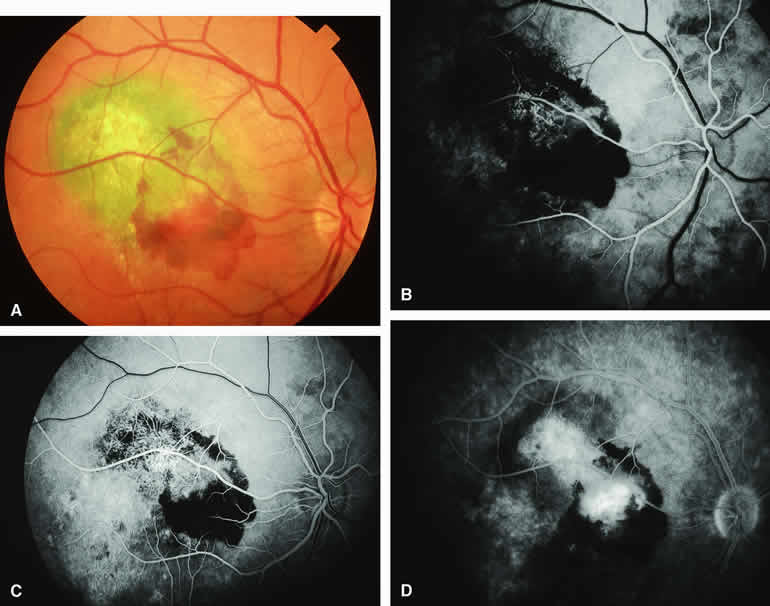

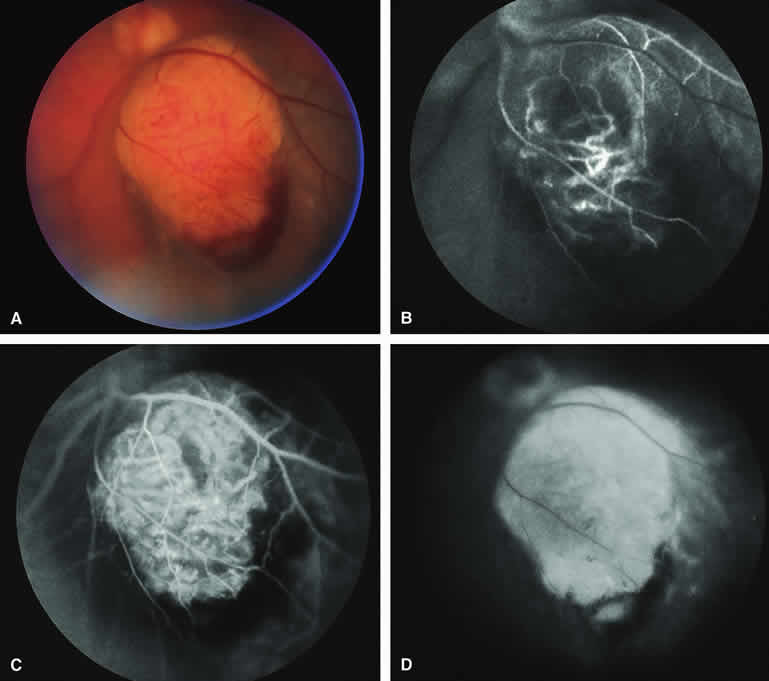

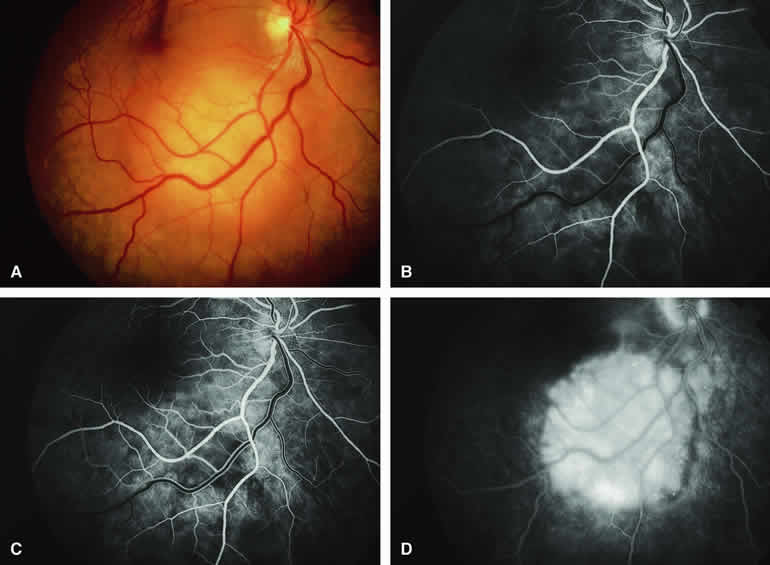

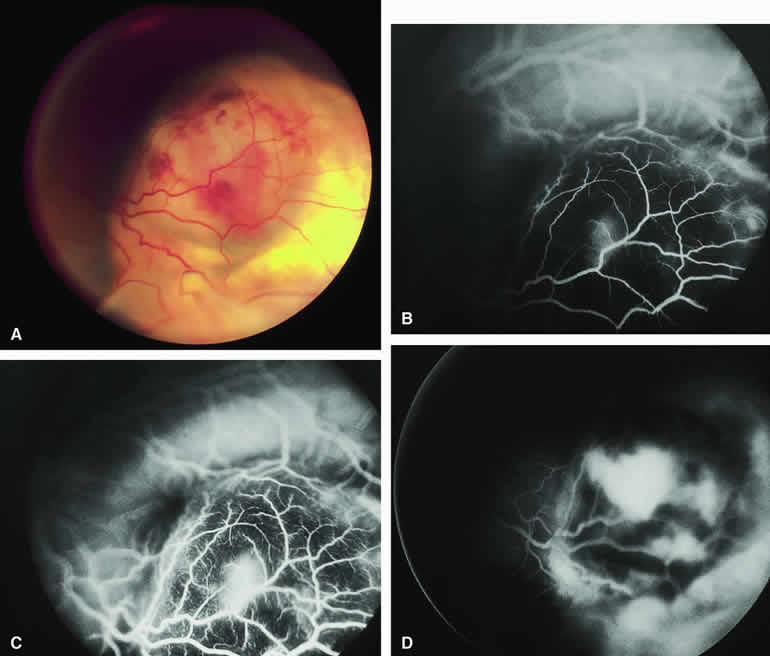

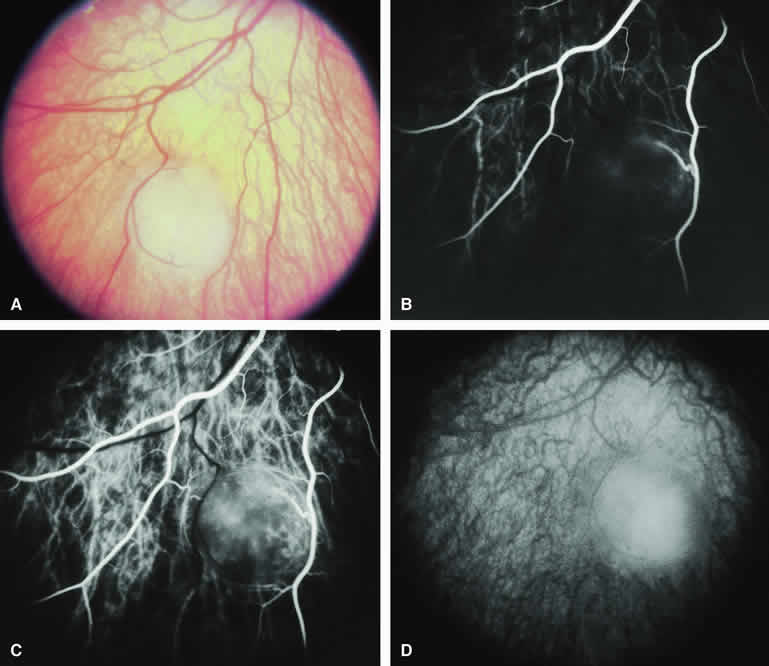

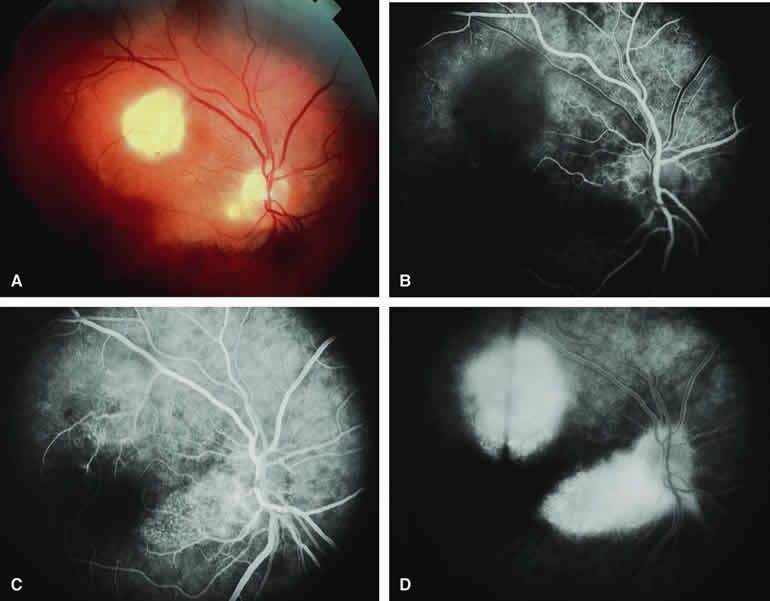

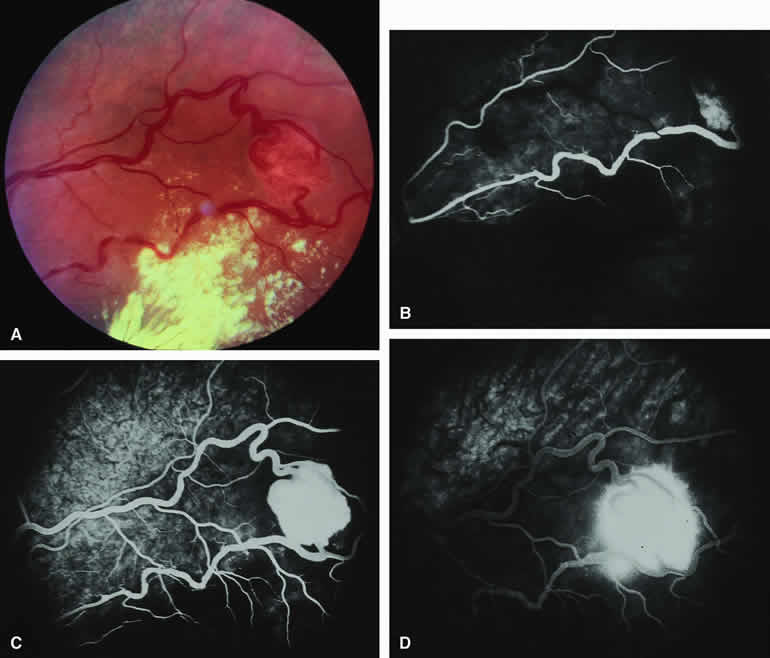

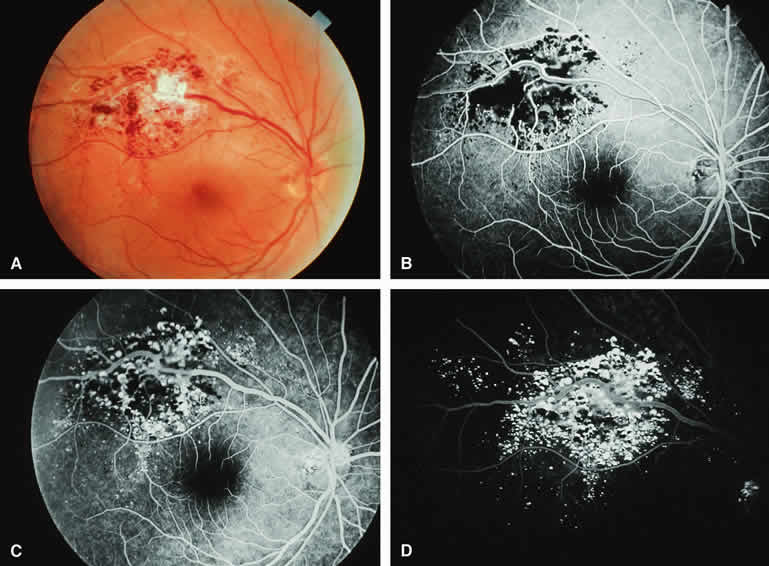

Choroidal Nevus with Drusen and Clumps of RPE Hyperplasia

If a choroidal nevus has drusen and RPE alterations on its surface (see Fig. 4A), fluorescein angiography (Fig. 4B, C, and D) tends to show patchy or stippled window defect hyperfluorescence corresponding to foci of RPE depigmentation, fluorescence blockage by clumps of RPE hyperplasia on the surface of the lesion, and late staining of at least some of the drusen. These features are not usually as evident on ICG angiography as they are on fluorescein angiography.

Choroidal Nevus Versus Melanoma

Small melanocytic choroidal tumors larger than 5 mm in diameter and thicker than 1 mm but without clearly invasive clinical features (e.g., nodular eruption through Bruch's membrane, retinal invasion) may be either benign nevi or small choroidal melanomas. Several features of these lesions have been identified as prognostic of the likelihood of subsequent lesion enlargement,13 a surrogate indicator of the malignant potential of the tumor. Features suggestive of low growth potential and probable benign histology include thickness less than or equal to 1.5 mm, uniform gray-brown coloration of the lesion, and drusen and RPE clumping on the surface of the lesion. In contrast, features suggestive of higher growth potential and probable malignant histology include thickness greater than 1.5 mm, nonuniform coloration of the lesion, prominent clumps of lipofuscin pigment on the surface of the lesion, and serous subretinal fluid overlying and surrounding the lesion. None of these features is a reliable indicator of the underlying histologic nature of the tumor; however, the greater the number of unfavorable features, the greater the likelihood of lesion enlargement if it is followed without treatment after initial detection.

Choroidal Nevus Versus Melanoma with Bland Surface Features

Several authors have evaluated fluorescein and ICG angiography as differential diagnostic tools for differentiating between large benign choroidal nevi and small malignant choroidal melanomas.9, 10 An example of such a lesion evaluated by fluorescein angiography is presented as Figure 5. Some common assertions based on these studies include the following. If the lesion is a nevus, fluorescein angiography is likely to show hypofluorescence of the lesion throughout the study, absence of large-caliber intralesional blood vessels, and lack of late smudgy hyperfluorescence resulting from leakage from these vessels. In contrast, if the lesion is a melanoma, fluorescein angiography is likely to show at least some intralesional tumor blood vessels, some patchy or smudgy fluorescein leakage from those blood vessels, and at least patchy or smudgy late fluorescence of the tumor. ICG angiography is more likely to reveal intralesional blood vessels within bland appearing small melanocytic choroidal lesions (especially darkly melanotic lesions) than is fluorescein angiography, and lesions with prominent intralesional blood vessels are generally regarded as more likely to be melanomas. Unfortunately, there have been no confirmatory angiographic-histopathologic correlation studies of small melanocytic choroidal tumors in the nevus versus melanoma category to confirm or refute these assertions. At best, this author regards the fluorescence angiographic features of bland appearing small melanocytic choroidal tumors as suggestive but not confirmatory of the pathologic nature of the tumor.

Choroidal Nevus Versus Melanoma with Prominent Lipofuscin Pigment Clumps

If one obtains a fluorescein angiogram on a small melanotic choroidal lesion (nevus versus melanoma) that has prominent clumps of lipofuscin pigment on its surface (Fig. 6), the pigment clumps appear intensely hypofluorescent throughout the study. This appearance is attributable to the complete blocking of choroidal fluorescence by the lipofuscin. ICG angiography does not show lipofuscin pigment clumps on the surface of the tumor as well as fluorescein angiography does.

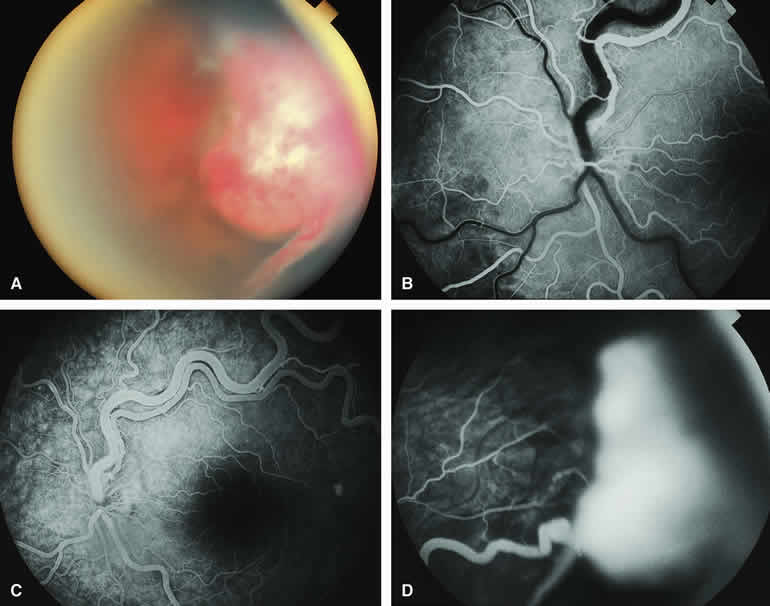

Choroidal Nevus Versus Melanoma with Overlying Serous Subretinal Fluid

A blister of serous subretinal fluid sometimes develops over and around a presumed choroidal nevus (Fig. 7A), especially if the lesion is located in the macula.11 If one performs a fluorescein angiogram on a small melanocytic choroidal lesion (nevus versus melanoma) that has shallow overlying serous subretinal fluid (see Fig. 7B, C, and D), one or more hyperfluorescent leak sites may show up slowly at the RPE level as the study progresses. In some cases, fluorescein will clearly leak from those foci into the overlying serous subretinal fluid. ICG angiography does not show hyperfluorescent leak sites at the RPE level as well as fluorescein angiography does.

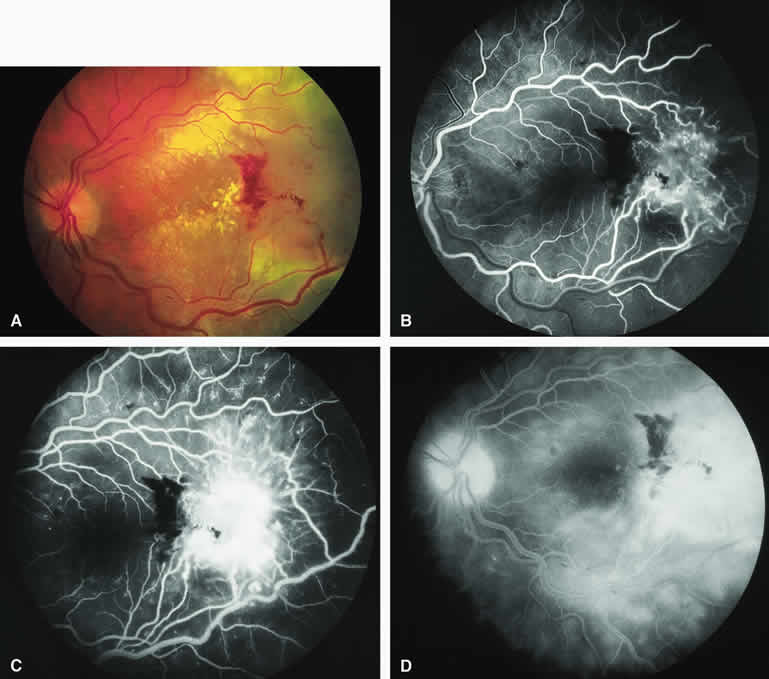

Choroidal Nevus Versus Melanoma with Choroidal Neovascular Membrane

A choroidal neovascular membrane occasionally develops from the surface of a small melanocytic choroidal tumor (nevus versus melanoma).12 This vascular structure can usually be anticipated because of the presence of ophthalmoscopically evident hemorrhagic or exudative subretinal fluid overlying a portion of the tumor (Fig. 8A). Fluorescein angiography in such cases (see Fig. 8B to D) generally reveals the neovascular membrane as a relatively well-defined vascular network that fluoresces brightly in the early frames of the study and leaks progressively by the late frames. If the subretinal fluid is grossly hemorrhagic, ICG angiographymay show the choroidal neovascular network better than does fluorescein angiography.

|

Fluorescence Angiographic Detection of Lesion Enlargement

Small melanocytic choroidal lesions in the nevus versus melanoma category are frequently monitored periodically following initial documentation for enlargement or other indicators of possible malignant behavior. Fluorescein angiography sometimes defines the basal area of these lesions better than does fundus photography, but ICG angiography is clearly the preferred technique for this purpose. If one elects to follow a small melanocytic choroidal tumor without treatment, comparative fluorescence angiography can be used to identify slight lesion enlargement that is not clearly evident by ophthalmoscopy or comparison of fundus photographs. Because benign choroidal nevi can and do enlarge, however, detection of subtle lesion enlargement by fluorescence angiography probably has limited differential diagnostic value in these lesions.

CHOROIDAL MALIGNANT MELANOMA

Choroidal malignant melanoma is the most common primary malignant intraocular neoplasm of adults. It has substantial local growth potential in addition to its well-known propensity to metastasize and, thereby, prove fatal to the host. Fluorescence angiography can provide evidence in support of the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma but is rarely if ever sufficient by itself to establish the diagnosis. Several ophthalmoscopically detectable features of clinically diagnosed melanocytic choroidal tumors are strongly indicative of their malignant potential. These include tumor diameter substantially greater than 7 mm, tumor thickness substantially greater than 3 mm, prominent intralesional large-caliber blood vessels, nodular apical eruption of the tumor through Bruch's membrane, invasion of the overlying retina by the tumor, and a prominent nonrhegmatogenous retinal detachment with shifting subretinal fluid.

Several distinct fluorescein and ICG angiographic patterns have been associated with choroidal melanomas.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 These distinct patterns depend on the degree of pigmentation of the tumor cells, the thickness of the tumor, the presence or absence of eruption of tumor through the overlying Bruch's membrane, and the presence or absence of retinal invasion by the tumor.

Melanotic Choroidal Melanoma Without Invasive Features

The typical choroidal melanoma that has not broken through Bruch's membrane generally appears as a gray-brown to dark brown, dome-shaped, solid choroidal mass (Fig. 9A). The overlying retina commonly appears normal except that it is draped over the choroidal tumor. Fluorescein angiography (see Fig. 9B, C, and D) typically shows the tumor to be relatively hypofluorescent during the early frames of the study. If prominent clumps of orange lipofuscin pigment are present on the surface of the tumor, they will appear intensely hypofluorescent throughout the study because of blockage of the underlying choroidal and tumor vascular fluorescence. During the arterial phase frames of the study, several ill-defined large-caliber deep intralesional blood vessels may be identifiable against the generally hypofluorescent background. As the study continues, these large intralesional blood vessels leak progressively so that the surface of the lesion tends to appear hyperfluorescent by the late frames. Fluorescein may also accumulate in the overlying retina and retinal pigment epithelium as tiny discrete pinpoint foci of intense hyperfluorescence. If serous retinal detachment is present overlying and around the tumor, the fluorescein will leak through the retinal pigment epithelium and accumulate in the subretinal fluid by the late frames. The retinal vascular pattern of the overlying retina commonly appears unremarkable in these cases.

If ICG angiography is performed on a similar tumor (Fig. 10), the tumor mass generally appears more intensely hypofluorescent throughout the study and its intrinsic blood vessels appear more clearly visible than on fluorescein angiography. ICG slowly accumulates within the extracellular space of the tumor so that the tumor usually appears mildly hyperfluorescent, at least in part, in the late frames.

Amelanotic Choroidal Melanoma Without Invasive Features

If the choroidal melanoma being evaluated is relatively amelanotic (Figs. 11A and 12A), its large-caliber intralesional blood vessels will tend to show up more distinctly on both fluorescein angiography (see Fig. 11B, C, and D) and ICG angiography (see Fig. 12B, C, and D) than they would in a darkly melanotic choroidal melanoma. Despite its amelanotic color, the cellular component of the mass tends to be at least mildly hypofluorescent relative to the adjacent uninvolved choroid during the early frames of the study. As with melanotic melanomas, the mass usually appears at least mildly hyperfluorescent in the late-phase frames (see Figs. 11D and 12D).

Choroidal Melanoma With Nodular Eruption Through Bruch's Membrane

If a choroidal melanoma has erupted through Bruch's membrane (Figs. 13A and 14A), it forms an apical nodule that is generally hypomelanotic and contains many large-caliber blood vessels. Fluorescein angiography of these tumors (see Fig. 13B, C, and D) typically shows hypofluorescence of the base of the lesion during the early frames, relatively rapid filling of the prominent blood vessels in the apical nodule during the venous and recirculation frames, and intense late staining of the apical nodule resulting from progressive fluorescein leakage by the late-phase frames. Similarly, ICG angiography of these tumors (see Fig. 14B, C, and D) also shows relative early hypofluorescence of the tumor base, early filling of prominent intralesional blood vessels within the apical nodule, intense staining of the apical nodule by the recirculation phase frames, and persistent late hyperfluorescence of the mass.

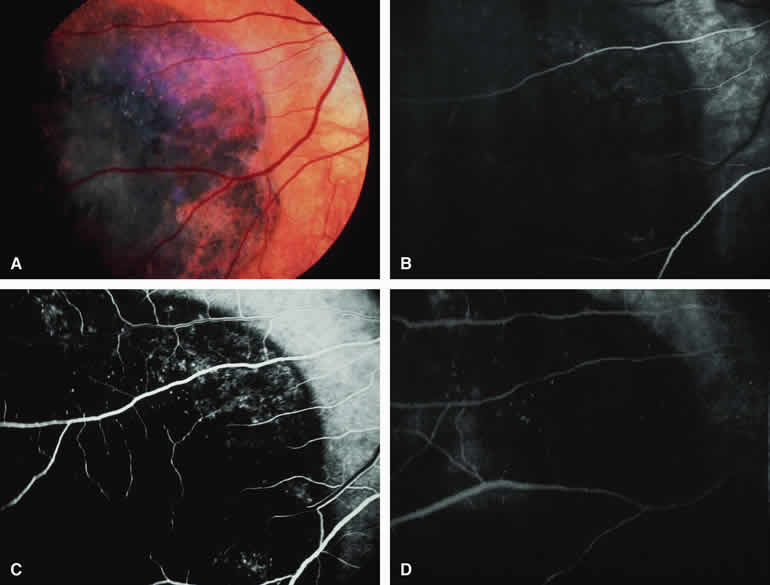

Choroidal Melanoma with Retinal Invasion

Occasional choroidal melanomas develop darkly melanotic patches of retinal invasion on their surface. These patches appear as homogeneous dark brown velvety lesions obscuring the examiner's view of the large retinal vessels (Fig. 15A). Fluorescein angiography of such a lesion (see Fig. 15B, C, and D) shows the darkly pigmented mass to be completely nonfluorescent throughout the entire study. The retinal blood vessels at the margins of the lesion are often abnormal and leaky, as might be expected on the basis of the associated retinal invasion.

CHOROIDAL METASTATIC CARCINOMA

The typical metastatic carcinoma to the choroid is a yellow, placoid choroidal tumor (Figs. 16A and 17A) associated with shallow subretinal fluid out of proportion to the size of the lesion. Atypical metastatic tumors to the choroid include some cutaneous melanomas, which tend to appear golden brown to dark brown (Fig. 18A), carcinomas that have prominent intralesional blood vessels and, therefore, appear red to orange (Fig. 19A), and rare instances in which a metastatic carcinoma focally erupts through Bruch's membrane to simulate a choroidal melanoma (Fig. 20A). The fluorescein and ICG angiographic features of metastatic carcinomas to the choroid have been described by multiple authors.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 22, 23

Typical Amelanotic Choroidal Metastatic Tumor

On fluorescein angiography, the typical metastatic tumor (see Figs. 16B, C, and D and 17B, C, and D) appears relatively hypofluorescent in the early frames of the study but becomes progressively more fluorescent as the study continues. Few, if any, intralesional blood vessels are demonstrable. Because of the damaging effects of the expanding choroidal tumor on the overlying retinal pigment epithelium, diffuse or multifocal hypofluorescence and hyperfluorescence are often noted at the RPE level overlying the lesion. In addition, pinpoint hyperfluorescent foci at the RPE level, which are generally attributed to microcystic RPE degeneration, commonly become apparent over the surface of the tumor by the late frames. Fluorescein typically leaks through the retinal pigment epithelium to accumulate in the overlying and surrounding subretinal space by the late frames.

ICG angiography of a typical metastatic choroidal carcinoma23 reveals generalized hypofluorescence of the mass in the early frames, absence of any large-caliber intralesional blood vessels, and mild late hyperfluorescence of the entire lesion. In some lesions, smudgy large-caliber choroidal blood vessels passing through or superficial to the mass can be visualized during the early-to midphase frames of the angiogram. As with other choroidal tumors, ICG angiography seems to show the full basal extent of the tumor substantially better than does fluorescein angiography. In some patients, it even reveals small metastatic choroidal lesions that are not evident by ophthalmoscopy or fluorescein angiography.

Melanotic Metastatic Choroidal Tumor (Metastatic Cutaneous Melanoma)

Occasional patients with metastasis from a primary cutaneous melanoma develop metastatic tumors in the choroid. If the metastatic choroidal lesions are darkly melanotic (see Fig. 18A), they will appear intensely hypofluorescent both early and late on fluorescence angiography (see Fig. 18B, C, and D). In contrast, if the lesions are relatively hypomelanotic, they may exhibit only mild relative hypofluorescence early. Most hypomelanotic metastatic melanomas to the choroid appear relatively hyperfluorescent on late frames of fluorescein angiograms because of progressive fluorescein leakage during the course of the study.

Vascularized Metastatic Choroidal Tumor

Some metastatic carcinomas to the choroid, including follicular thyroid carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and particularly choriocarcinoma, have been noted to be associated with prominent intralesional blood vessels that are apparently stimulated to develop by vasogenic humoral factors secreted by the tumor. These tumors tend to have a red to orange color and often give rise to spontaneous subretinal hemorrhages. An example of such a metastatic choroidal tumor is shown in Figure 19A. Fluorescence angiography of this tumor (see Fig. 19B to D) reveals an intralesional vascular network similar to that observed in many hypomelanotic melanomas. The tumor characteristically exhibits early filling of the intralesional blood vessels, intense fluorescence of the entire lesion shortly after initial vascular filling, and intense late staining with leakage of dye into the subretinal fluid. Consequently, detection of this intralesional vascular network does not rule out a metastatic carcinoma to the choroid.

Metastatic Carcinoma to Choroid with Apical Eruption Through Bruch's Membrane

The mushroom-like cross-sectional shape of a choroidal tumor (resulting from focal nodular eruption of the tumor through Bruch's membrane) is such a common feature of choroidal melanoma that many ophthalmologists believe it to be pathognomonic of this neoplasm. Despite this belief, occasional metastatic carcinomas also exhibit this morphologic pattern. Not surprisingly, these metastatic tumors are almost always mistaken clinically for choroidal melanomas. An example of a metastatic choroidal tumor with a nodular eruption through Bruch's membrane is shown in Figure 20A. In contrast with a choroidal melanoma with this feature, a metastatic choroidal tumor with nodular apical extension through Bruch's membrane usually has few if any prominent intralesional blood vessels within the nodule. On fluorescence angiography (see Fig. 20B, C, and D), the apical nodule of a metastatic choroidal tumor is much more likely to exhibit generalized hypofluorescence and much less likely to exhibit fluorescent large-caliber intralesional blood vessels than a similar nodule associated with a choroidal melanoma.

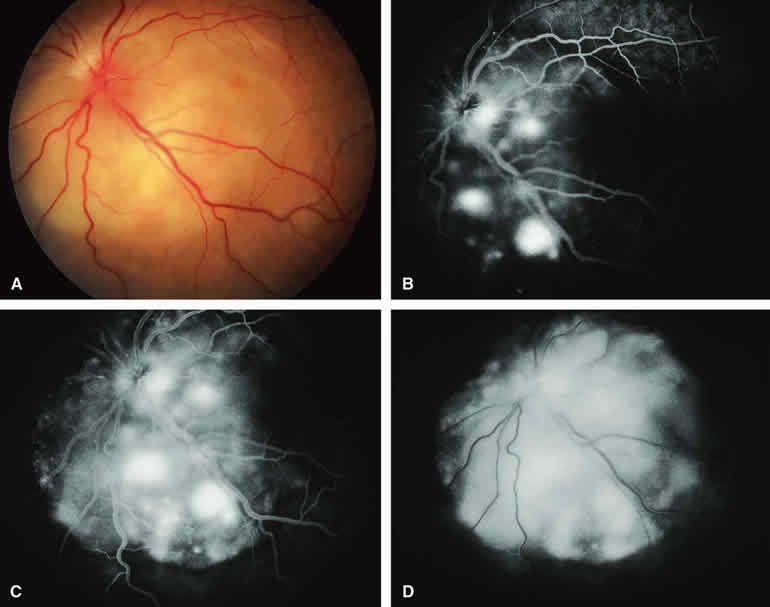

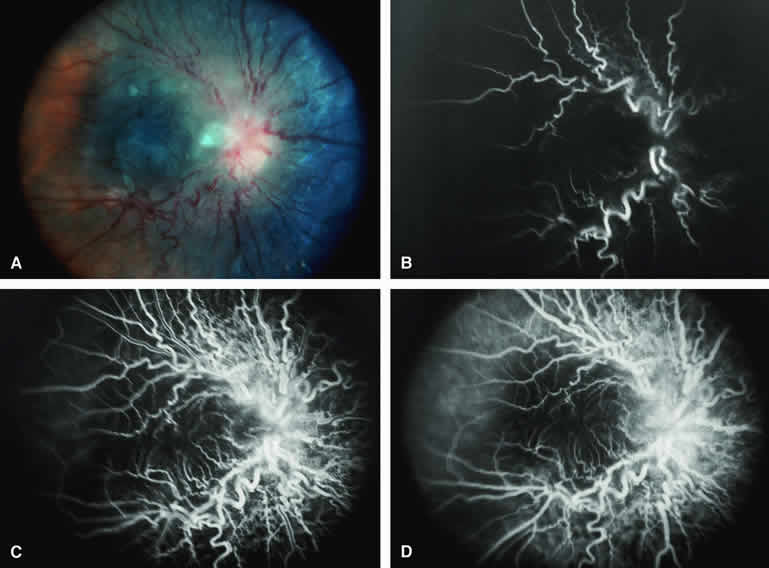

CIRCUMSCRIBED CHOROIDAL HEMANGIOMA

The circumscribed choroidal hemangioma is a benign neoplasm versus hamartoma composed of mature choroidal vascular channels. Fluorescein and ICG angiographic features of these tumors have been described by multiple authors.21,22 The typical circumscribed choroidal hemangioma (Figs. 21A and 22A) is a reddish orange, extremely ill-defined, posterior choroidal tumor that is 5 mm or less in basal diameter and 2 to 3 mm or less in thickness. The overlying retina commonly appears cystic by fundus biomicroscopy, and the retina is often noted to be shallowly detached overlying and surrounding the mass. The posterior margin of virtually all circumscribed choroidal hemangiomas is located within two disc diameters from the optic disc or foveola or both.

Fluorescein angiography of a typical circumscribed choroidal hemangioma (see Fig. 21B, C, and D) shows prominent fluorescence of multiple large-caliber intralesional vessels concurrent with or even before the earliest filling of the normal choroidal and retinal blood vessels. By the late retinal arterial phase frames, the entire lesion is usually diffusely and intensely hyperfluorescent without identifiable distinct intralesional vessels. Fluorescein leaks through the characteristically degenerated overlying retina pigment epithelium into the subretinal space and commonly stains the subretinal fluid and retina diffusely in the late-phase frames.

ICG angiography of a typical circumscribed choroidal hemangioma (see Fig. 22B, C, and D) reveals rapid filling of large-caliber intralesional blood vessels, early intense fluorescence of the vascular tumor, persistent hyperfluorescence of the tumor for 10 to 15 minutes or longer, and late washout of central fluorescence with residual marginal fluorescence by the 20- to 30-minute postinjection frames. This ICG angiographic pattern appears to be almost pathognomonic of circumscribed choroidal hemangiomas and is, therefore, of substantial differential diagnostic value. ICG angiography usually reveals the full extent of the base of the tumor much better and more completely than does fluorescein angiography.

Circumscribed Choroidal Hemangioma with Overlying Fibrous Metaplasia of Retinal Pigment Epithelium

Some circumscribed choroidal hemangiomas exhibit prominent fibrous metaplasia of the retinal pigment epithelium overlying much of the lesion (Fig. 23A). The fibrous metaplasia appears as a white layer of connective tissue deep to the cystic sensory retina overlying the tumor. Fluorescein angiography of these tumors (see Fig. 23B, C, and D) often shows blockage of much of the early vascular filling. In contrast, ICG angiography generally shows the characteristic pattern of intense early hyperfluorescence and late central washout despite the fibrous tissue on the surface of the tumor.

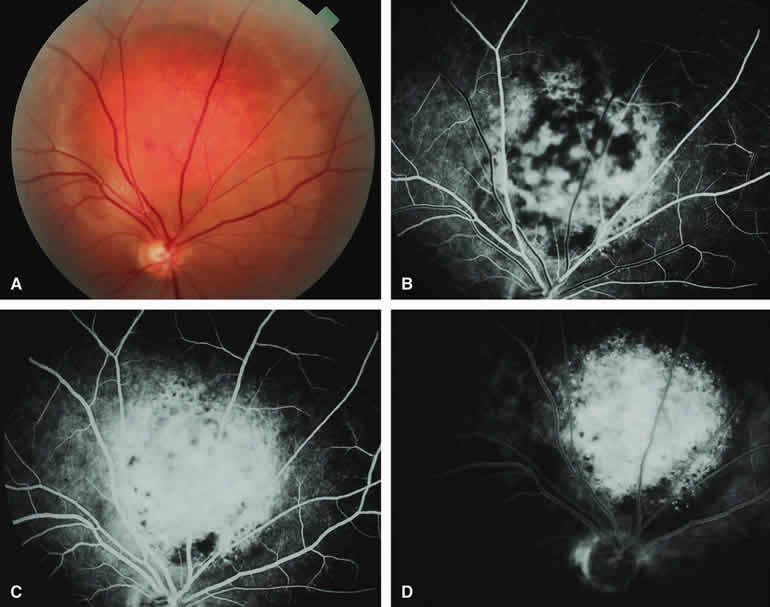

CHOROIDAL OSTEOMA

The choroidal osteoma is an acquired benign bony tumor of the choroid. It affects women predominantly and usually becomes apparent by the second to third decades of life. The lesion can impair vision substantially but has no malignant potential. The typical lesion appears as a yellowish white to yellow-orange, circumpapillary or juxtapapillary, platelike choroidal mass with well-defined margins (Fig. 24A). These lesions occur bilaterally in approximately 20% to 25% of affected people. Ocular ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scanning are of great value in confirming the clinical diagnosis. Fluorescein and ICG angiography of these tumors have been reported by several authors.29, 30, 31

Typical Choroidal Osteoma

On fluorescein angiography (see Fig. 24B, C, and C), the characteristic lesion shows numerous spidery superficial intralesional blood vessels in the early frames of the study and patchy or diffuse staining of most or all of the lesion in the late frames. This pattern does not appear to be pathognomonic.

ICG angiograms of several choroidal osteomas have been reported.29,30 These lesions exhibited a prominent early pattern of small intralesional blood vessels, some of which were not evident on fluorescein angiography. Although the lesions appeared generally hypofluorescent early, leakage from the intralesional blood vessels resulted in variable late hyperfluorescence. Patchy areas and foci of late hypofluorescence have been attributed to blockage of choroidal fluorescence by the bone or hyperplastic retinal pigment epithelium overlying the tumor. The full extent of the base of the lesion is generally revealed much more clearly by ICG angiography than by fluorescein angiography.

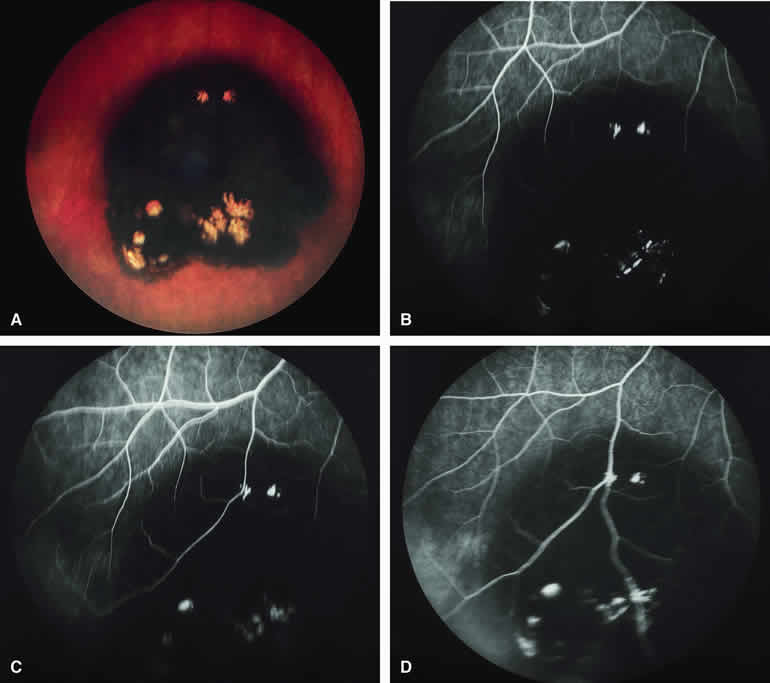

Choroidal Osteoma with Overlying Choroidal Neovascular Membrane

Because choroidal neovascularization is a relatively frequent complication of choroidal osteomas,31 fluorescence angiography may be performed to evaluate the possible presence and extent of this vascular lesion. When present (Fig. 25A), a choroidal neovascular membrane lesion will appear on fluorescein angiography (see Fig. 25B, C, and D) as an abnormal vascular network beneath the retinal pigment epithelium or sensory retina in the early frames of the study and as a smudgy hyperfluorescent lesion showing progressive increase in fluorescence and late staining with leakage in the late frames. If one treats this neovascular membrane by photocoagulation or photodynamic therapy, one can monitor the response of that lesion with a subsequent angiogram of the same type.